Cheviot Hills

A. L. King & Frankie King – subdividers

In 1912, prominent Palms husband and wife Abraham Lincoln (A.L.) King (1866-1927) and Frances Louise “Frankie” (Laforge) King (1870-1966) recorded Tract 1938, a 127-acre subdivision of “a portion of Lot 1, Tract of Francisco Higuera” in the Rancho Rincón de los Bueyes – an unincorporated part of Los Angeles County. They had bought the land in 1896 for $7,000 (about $250,000 in 2023 dollars) or about $55 per acre. They farmed the land, with Mr. King reporting “having 14,000 sacks of barley and wheat” in 1897. (L. A. Herald, Sept. 8, 1897.)

In March 1923, voters added Tract 1938 (and other lands) to Los Angeles city limits through the “Ambassador Annexation” (a.k.a. Ambassador Addition). The following December, the Kings filed another tract map, Tract 6741, a “subdivision” of Tract 1938, which was coextensive with the earlier tract. The Tract 6741 map shows only two streets: Motor Avenue and Cheviot Drive. (In 1942, Cheviot Drive’s name was extended south of Manning Avenue to replace the block long Abbottson Road in the Country Club Highlands tract.) The Kings soon sold their undeveloped subdivision to Frans Nelson & Sons for $2,100 an acre, totaling $266,700 (about $4.7 million in 2023 dollars).

Frans Nelson & Sons – developers

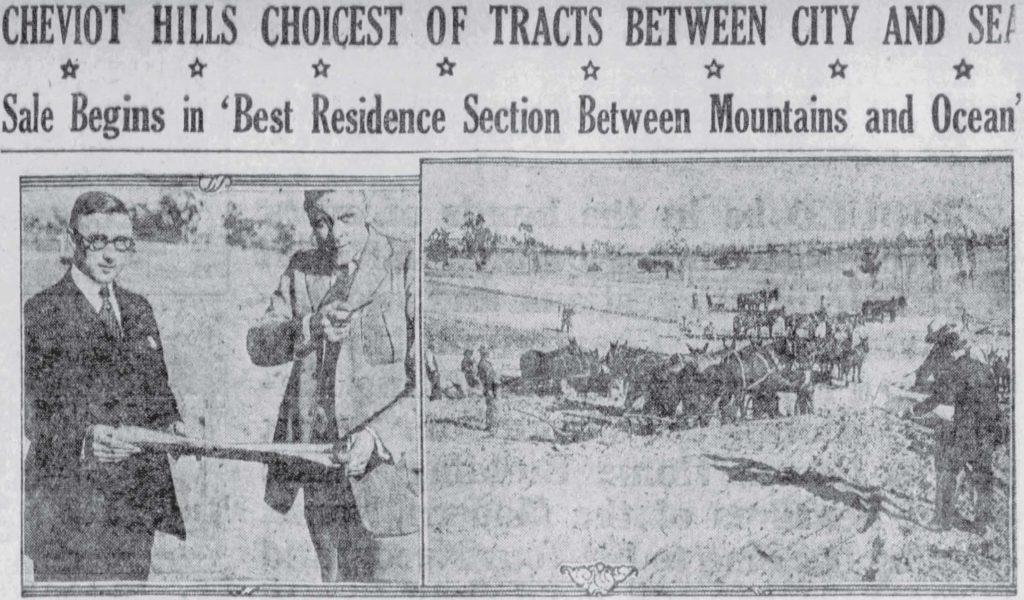

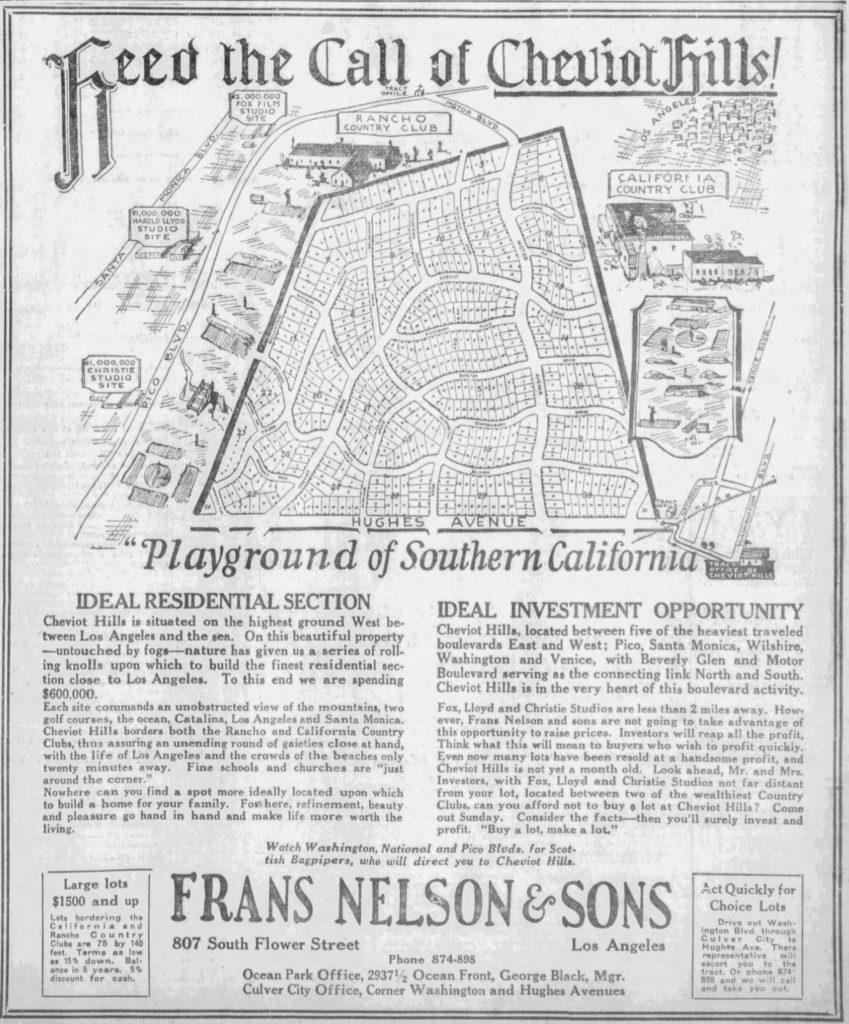

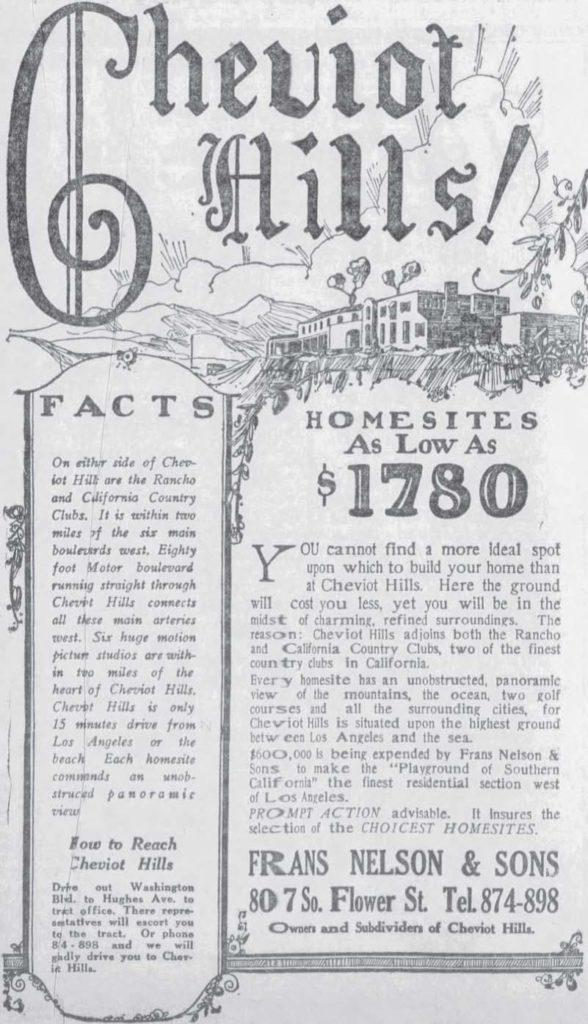

Frans Nelson & Sons “opened” Cheviot Hills on August 19, 1923 and started offering lots for sale starting November 11, 1923 – which was nearly a year before the City of Los Angeles approved the tract map. On May 12, 1924, Frans Nelson & Sons filed a subdivision map for Tract 7264 (coextensive with Tracts 6741 and 1938 discussed above) which would be marketed as Cheviot Hills. Frans Nelson & Sons, Inc., was listed as owner; A. L. King was listed as mortgagee. The “& Sons” of Frans Nelson & Sons were George Alfred Nelson (1885-1924) and Harvey Frans Nelson (1893-1972).

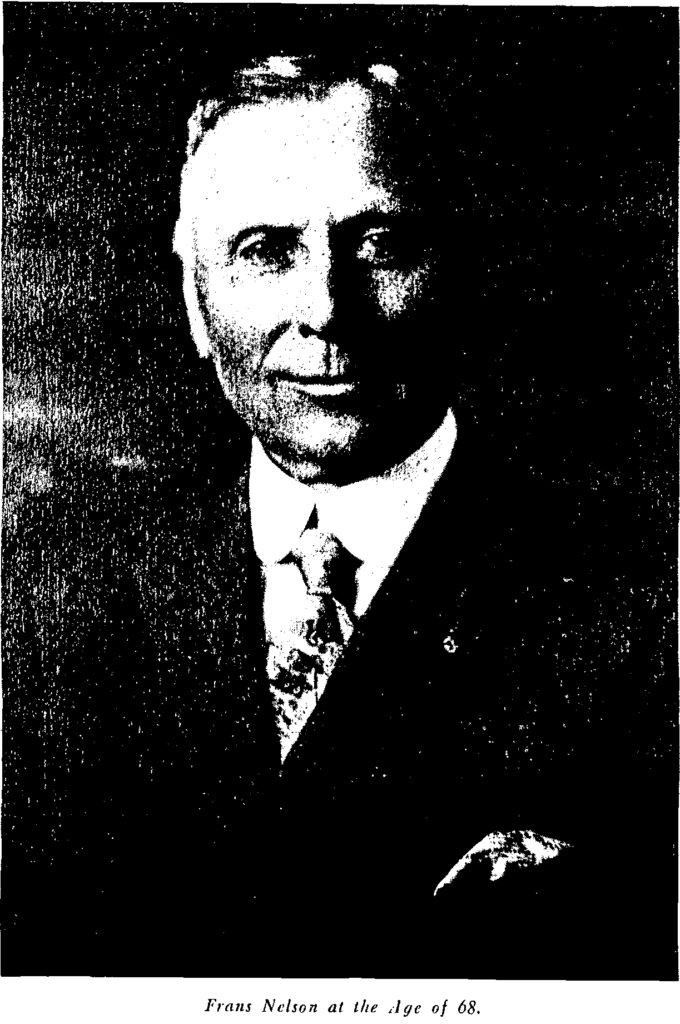

Frans Oscar Nelson (1859-1948) (pronounced FrAHns), acknowledged the Kings (at least Mr. King) in a November 1923 newspaper article he wrote to promote Cheviot Hills: “Twenty-seven years ago, a westward pioneer by the name of A. L. King purchased this tract of land, which consists of 127 acres, for the mere song of $7,000.” (L. A. Evening Express, Nov. 3, 1923.)

A month later, in December 1923, Erskine Edward “E. E.” Mix (1893-1952) – of “the E. E. Mix Engineering and Construction Company who are putting in all the improvements at Cheviot Hills for Frans Nelson and Sons, subdividers” – wrote an article in the same paper promoting Cheviot Hills.

One block of Cheviot Hills will be devoted exclusively for a neighborhood business center, the rest of the tract will be one family residence property. Restrictions as to the architecture of the business buildings and the materials used will be governed by Frans Nelson and Sons.

Dec. 1, 1923, L. A. Evening Express.

Building restrictions for all homes on Motor boulevard, Cheviot drive, Queensbury and Ballantrae, the latter two thoroughfares bordering the Rancho and California Country Clubs, and also Glenbar, which is the highest property on Cheviot Hills, overlooking all the surrounding country, will be a minimum of $7500 for a period of 25 years. Building restrictions of $5000 for 25 years have been placed on all other lots. Specifications as to building materials are stucco, stone, artificial stone and brick. The outside elevations of houses are subject to approval of the architectural department of Frans Nelson and Sons. The average lot at Cheviot Hills is 65 feet by 140 feet.

Some of what Mr. Mix wrote did not come to fruition. For instance, there would be no “neighborhood business center” – and no Ballantrae street. However, as predicted, Frans Nelson & Sons did impose restrictions: homes built on Motor Avenue or facing the country clubs would cost no less than $7,500 to build, while others would cost at least $5,000. (They also restricted setbacks, fence height, etc.) Incidentally, Monte-Mar Vista (to the north and east) started with a higher minimum house cost of $12,000, which was reduced to $4,000 during the Great Depression.

Those Cheviot Hills title restrictions continued only into the 1940s. However, the developer also applied racial restrictions that were meant to never expire:

no part of any of said lots shall ever, at any time, be used or occupied, or be permitted to be used or occupied by any person other than one of the White or Caucasian race, except such as are in the employ of the owner or tenants of said lots residing therein.

In 1948, our nation’s highest court held such racial restrictions unenforceable in Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 US 1 (1948). But Cheviot Hills had already been developed as a racially restricted subdivision. Prejudice was implicit in the Frans Nelson’s article promoting his tract and referencing “foreign colonies” – meaning, in more recent and anodyne terminology, ethnic enclaves or immigrant communities.

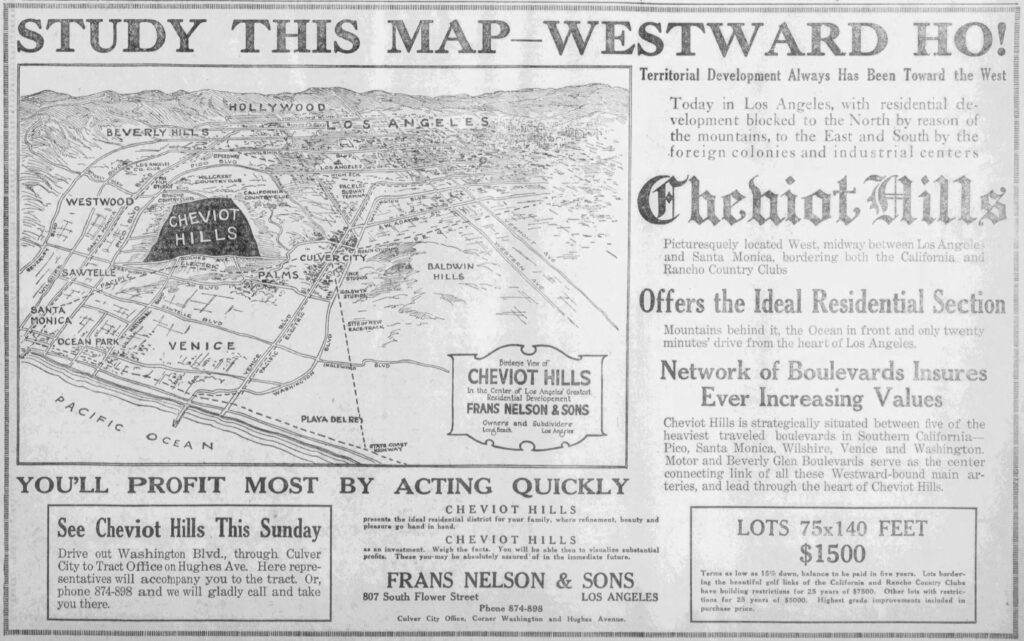

Today in Los Angeles with residential development blocked to the north by the mountains, to the east and south because of foreign colonies and industrial centers, it leaves only a westward movement for the development of residential sections.

(L. A. Evening Express, Nov. 3, 1923.)

Nelson’s same statement appeared in the earliest advertising for Cheviot Hills.

Nelson’s friend Ole Edward Hanson (1874-1940) used the “foreign colonies” phrase in deriding certain immigrants as unAmerican. Hanson had been the Mayor of Seattle (1918-1919), founded San Clemente (1925), and was associated with the development of Monte-Mar Vista. In January 1920, the Long Beach Press carried an anti-immigrant article featuring Hanson and highlighting the “foreign colonies” phrase. The article’s title, Milwaukee Needs Ambassador, Not Congressman, at Capital [sic], targeted Milwaukee’s immigrant, Jewish American, socialist congressman, Victor Luitpold Berger (1860-1929).

Ole Hanson … has made a study of the immigration problem ….

Long Beach Press (Jan. 29, 1920).

Hanson realizes, as do all thinking men, that our immigration policy in the past has been woefully wrong ….

“Our policy was immigration by gravitation, under which the immigrant sank to the lowest level. Now, I propose that we shall have immigration by invitation ….”

Under the Hanson plan no immigrant would be permitted to come to this country without a thorough physical, mental and economic examination in his own country.

Foreign Colonies.

This plan, Hanson believes, would do away with the menace of foreign colonies, which exist in so many places throughout the United States and which … prevent immigrants from learning Americanism and from becoming loyal citizens.

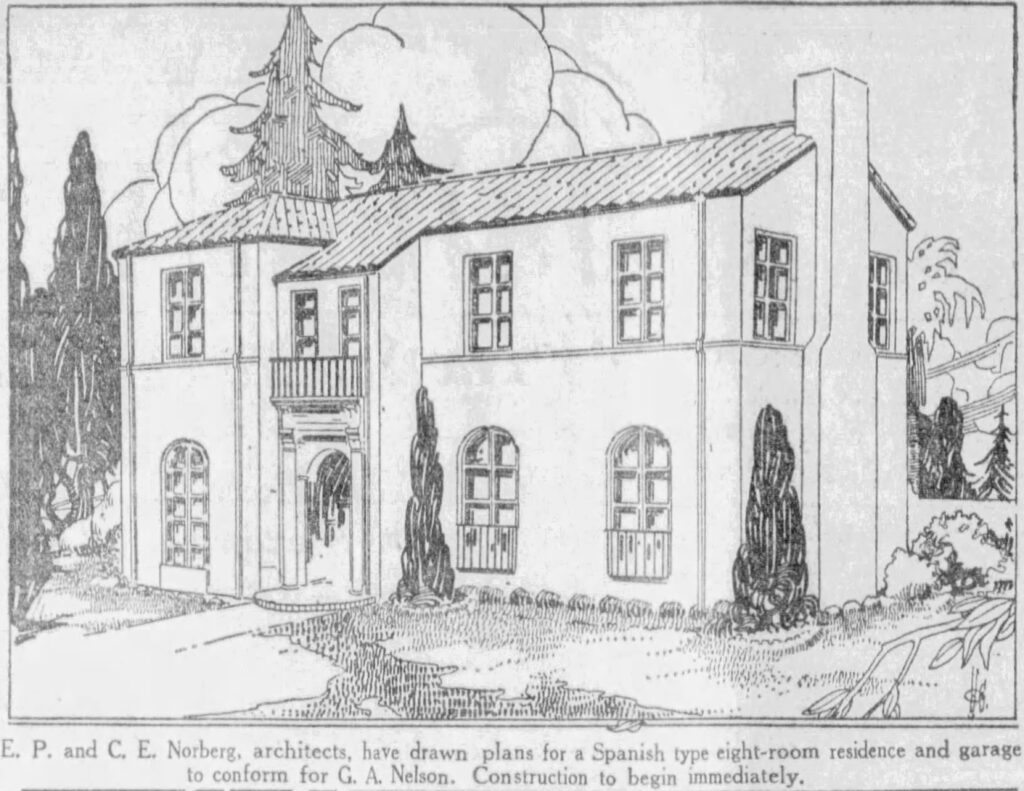

The November 3, 1923, Los Angeles Evening Express edition with Nelson’s article on Cheviot Hills also carried an advertisement for the tract with a drawing of George Nelson’s planned residence. Designed by father and son architects Charles Eric Norberg (1865–1943) and Elwin Paul Norberg (1889-1946), it appears (shown below) rather true to the design. Sadly, George would die of a sudden illness in January 1924 before moving in.

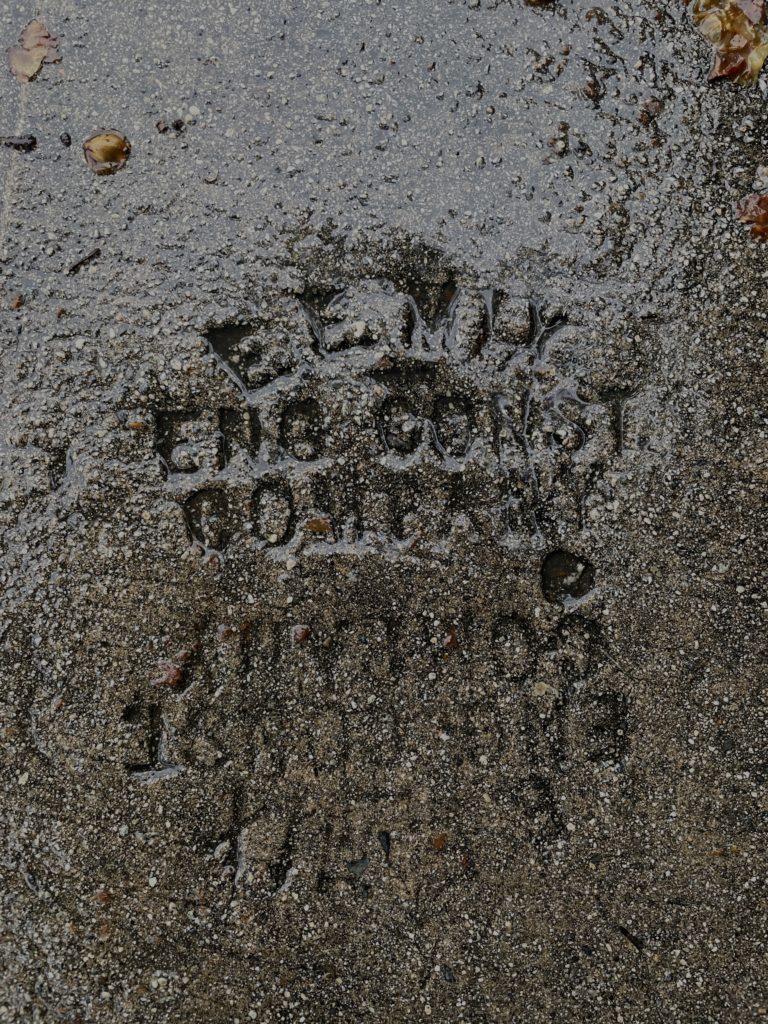

Construction chief E. E. Mix oversaw a “small army of men and 40 mules working overtime” to transform a barley field into a “high class residential section.” (L. A. Evening Express, Dec. 8, 1923.) (“E. E. Mix” is stamped on some Cheviot sidewalks.)

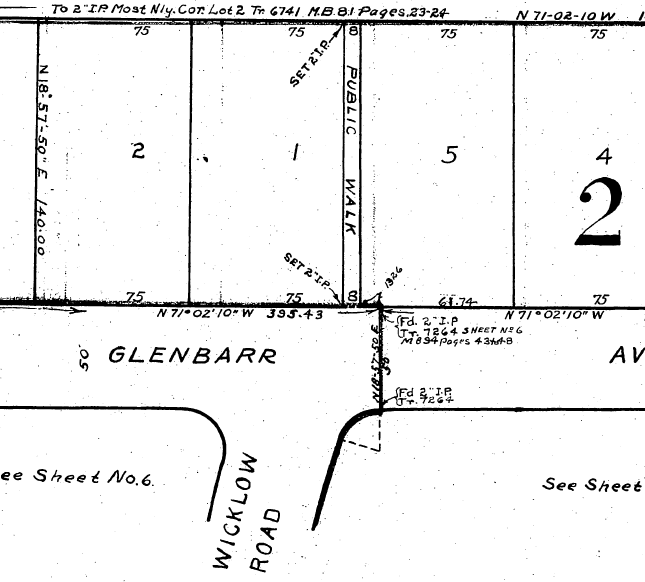

The Los Angeles City Council approved the Cheviot Hills tract on June 10, 1924, with the next order of business being approval of Monte-Mar Vista tract. In approving the latter, the City imposed the City Engineer’s two conditions: that Dumfries Road “be dedicated so as to give actual frontage on the boundary line of the tract” and “that a walk be substituted for Wicklow Road” (at Wicklow, north of Glenbarr Avenue). That “walk” is one of the strangest aspects of the layout – since it is a “walk to nowhere,” dead-ending half way across the block.

Frans Nelson, the Swedish-born retired Nebraska banker turned real estate developer (he had developed north Long Beach’s 560-lot “Fair Acres” subdivision), recounted in his biography that, even out in the “sticks,” empty lots were sold as quickly as they could be made ready:

To a cynical, “Wasn’t Cheviot Hills part of the West Los Angeles ‘sticks’ at that time?” Frans continued his half-amused recital.

“Yes, it was pretty far out then. We had to spend over $400,000 in improvements such as sidewalks, curbs, streets, electroliers, water and gas mains, and power lines. But as fast as the utilities went in the homes went up. We also built a clubhouse [Palomar Tennis Club] near the properties complete with plunge and tennis courts.”

Cheviot Hills builder E. E. Mix wrote, “All roads and drives in Cheviot Hills have been named after famous roads in Scotland. The reason for this is because the lay of the land is almost a replica of the famous Cheviot Hills which separates England and Scotland. It was for this reason we carried out the Scottish idea.” (Dec. 1, 1923, Los Angeles Evening Express.)

Decades later, Frans Nelson’s friend and biographer, Carroll Everard “Deke” Houlgate (1905-1959) (like Nelson, another former Nebraskan), elaborated on the (possibly apocryphal) story:

“When we got ready to put this new property on the market, my sales organization numbered about thirty, each of whom was nearly as enthusiastic as were Harvey, George, and I.

Frans Nelson, A Biography (by Deke Houlgate) (The Pueblo Press 1940)

“We decided to let them help select a name for the new subdivision and I arranged a contest among them for that purpose. Each salesman was asked to submit a name and upon those turned in we held a

contest. Final balloting determined our choice – Cheviot Hills!”

A natural question of, “Why Cheviot Hills?” drew a whimsical smile and the answer:

“One of our salesmen was a Scotchman by the name of Simpson. He turned in the name of a district in his homeland and when this name, Cheviot Hills, was finally selected offered the further suggestion, producing a map of Scotland, that the streets be given Scotch names.

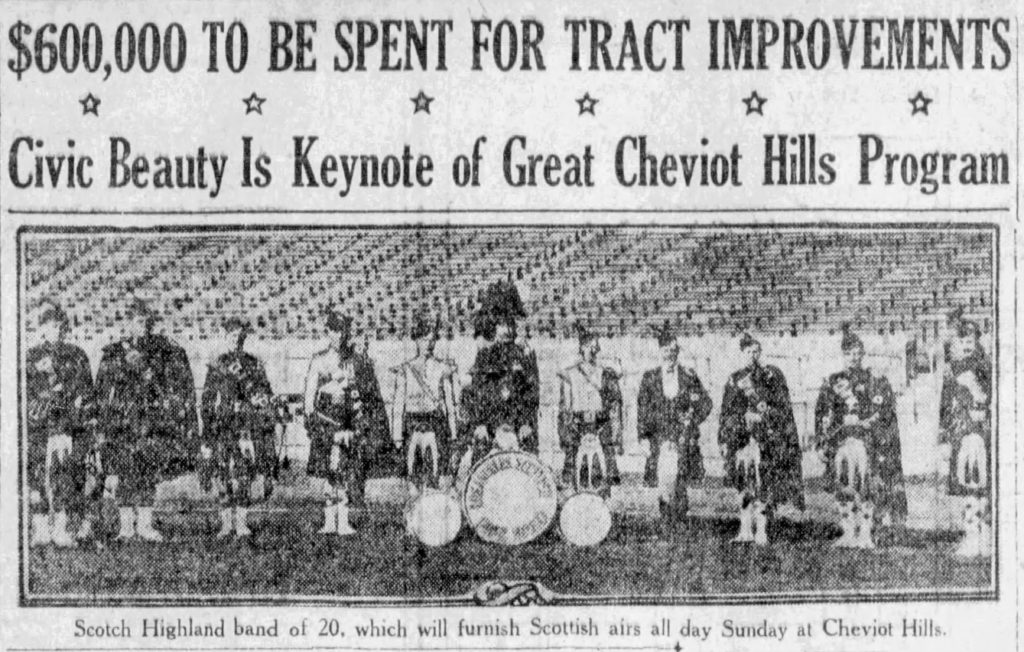

LAStreetnames.com questions the naming story: “I found no Simpsons on the company’s roster, so the story might be hogwash, but the moniker suited these golf course-adjacent hills and the Nelsons heavily played up the Scotland theme, with streets named after Scottish locales – Cheviot Drive was the first – and even bagpipers performing at sales events.”

In April 1927 article, “Whippets to Race Today,” showing Frans Nelson’s own house in Cheviot Hills, reported that “although Cheviot Hills has been developed only a short time, 80 per cent of the property has been sold and already seventy-one homes, ranging in value from $10,000 to $50,000, have been erected.” (L. A. Times, April 10, 1927.)

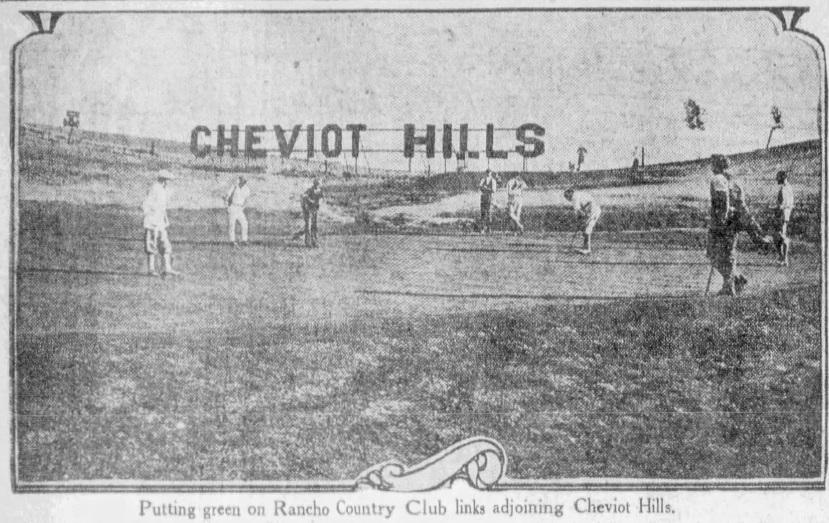

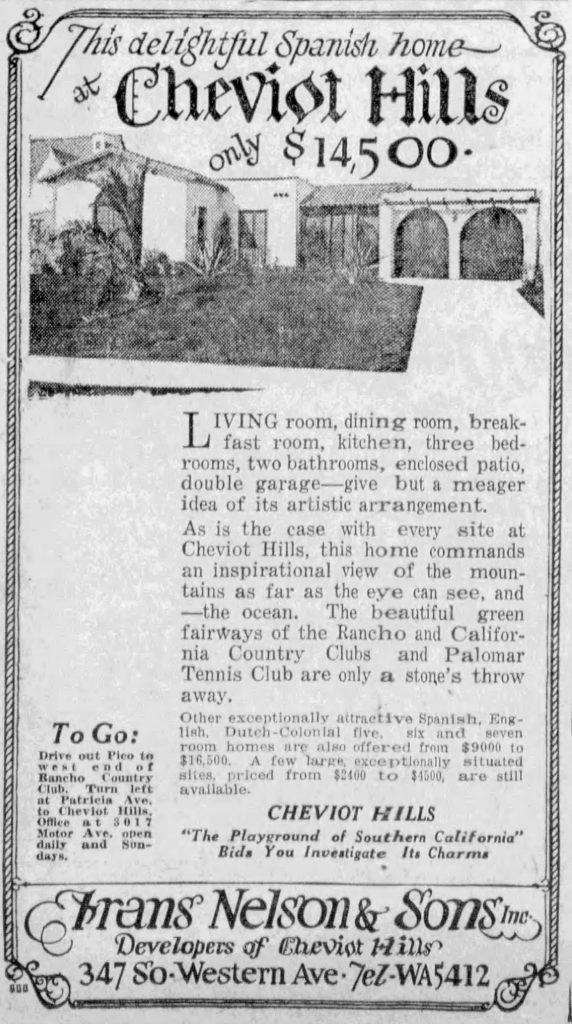

The new neighborhood was touted for its proximity to the Rancho Golf Club and California Country Club; Hillcrest Country Club, with a mostly Jewish membership, was never mentioned. Also noted were nearness to movie studios and “convenience to Los Angeles and the beach.” Lots in the “finest residential district between Los Angeles and the sea” were advertised from $1780, with homes beginning at $10,500.

Neff & Hurst – realtors

Harvey Nelson’s boyhood friend, Harold Grant Neff (1894-1981), was one of Cheviot Hill’s preeminent promoters. Harold was Harvey’s classmate at Omaha High School (class of 1913) and his best man when Lt. Harvey Nelson married Marian Norris (daughter of Nebraska Senator George W. Norris (1861–1944)), in Washington D.C. in 1918. Neff worked for the United States Geographic Survey Service in D.C. in 1920, the year he came to Harvey’s sister Bernice’s wedding in Nebraska. Beginning in 1929, Harold Neff partnered with Edward R. Hurst (1880-1943) to form the real estate office “Neff & Hurst.” Hurst was a Cheviot Hills resident and “an early member, past president of the California Country Club.” He would go on to be a director of the Los Angeles Realty Board and the Southern California and California Golf Associations. From offices at 3017 Motor Avenue, Neff & Hurst was the primary seller in the Cheviot Hills tract. The Los Angeles Times reported that, during 1931, Neff & Hurst did over $400,000 in business in Cheviot Hills: “Sixty homes were bullt and nearly all occupied.” By 1935, the Evening Star News’ Cheviot Chatter column called Neff the “‘mayor’ of Cheviot Hills.” Later, when the Walter H. Leimert Co. developed the adjacent Cheviot Knolls subdivision, Neff & Hurst (by then at 3131 Motor Avenue) were the exclusive selling agents.

Cheviot Hills did not sell as quickly as its developers might have wished. For one thing, the housing market crashed a few years after it hit the market. “The famous stock market bubble of 1925–1929 has been closely analyzed. Less well known, and far less well documented, is the nationwide real estate bubble that began around 1921 and deflated around 1926.” (Harvard Business School, Baker Library, Historical Collections, The Forgotten Real Estate Boom of the 1920s.) So, four years after the neighborhood opened, Frans Nelson was still promoting it, for example, with whippet races for which he provided the trophy.

Over the years, several subdivisions surrounding Cheviot Hills (such as Country Club Highlands, Monte-Mar Vista, and Cheviot Knolls) have lost their individual identities and collectively are called Cheviot Hills, with the original sometimes called “Old Cheviot.” The Cheviot Hills subdivision is distinguished by “Frans-Nelson & Sons” stampings in streets, sidewalks, and curbs and by (CD 803 – style electrolier) concrete lampposts.