Alexander Hamilton High School

In fall 1931, Alexander Hamilton High School opened in the Palms section of Los Angeles. It served Culver City, much of West Los Angeles, and families up to Mulholland Highway to the north. Thomas Hughes Elson (1879-1942) was the principal.

“Alexander Hamilton opened its doors to an initial enrollment of 798 students. The school at that time contained the seventh, eighth and ninth years of school in addition to the normal three grades of high school; but the two lowest grades were successively dropped in the years 1932 and 1934, the ninth grade being retained for the benefit of the graduates of Culver City’s eight-year grammar schools.” (Anna Mae Mason’s Master’s Thesis.)

With the opening of Palms Junior High School in September 1949, Hamilton no longer took in seventh graders: “Hamilton will no longer be a four year high school, but will range from the tenth through twelfth grades,” reported the school newspaper, The Federalist.

The Edifice

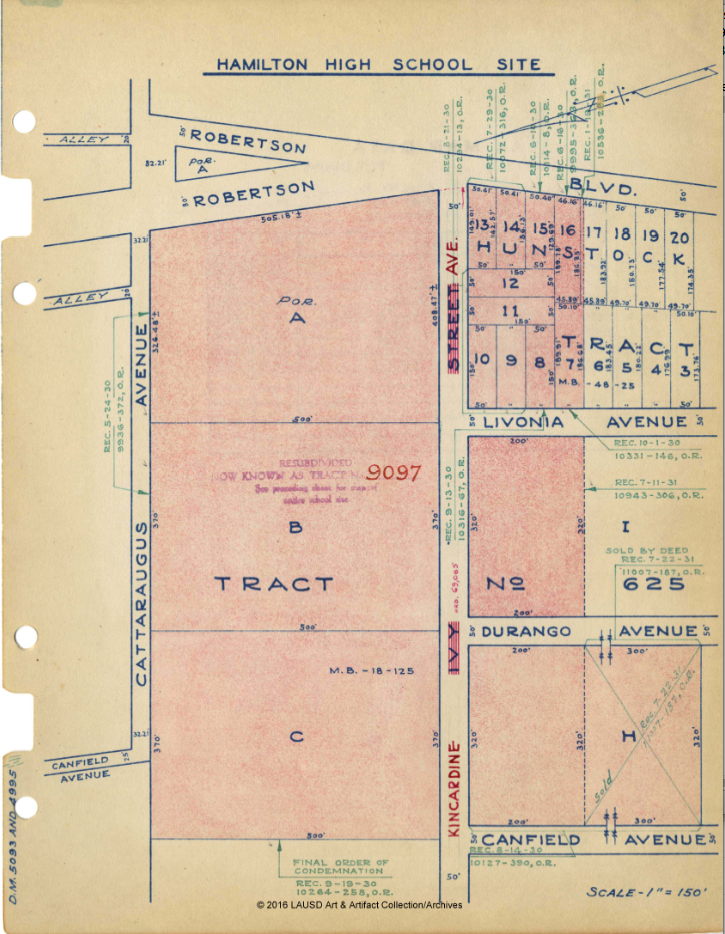

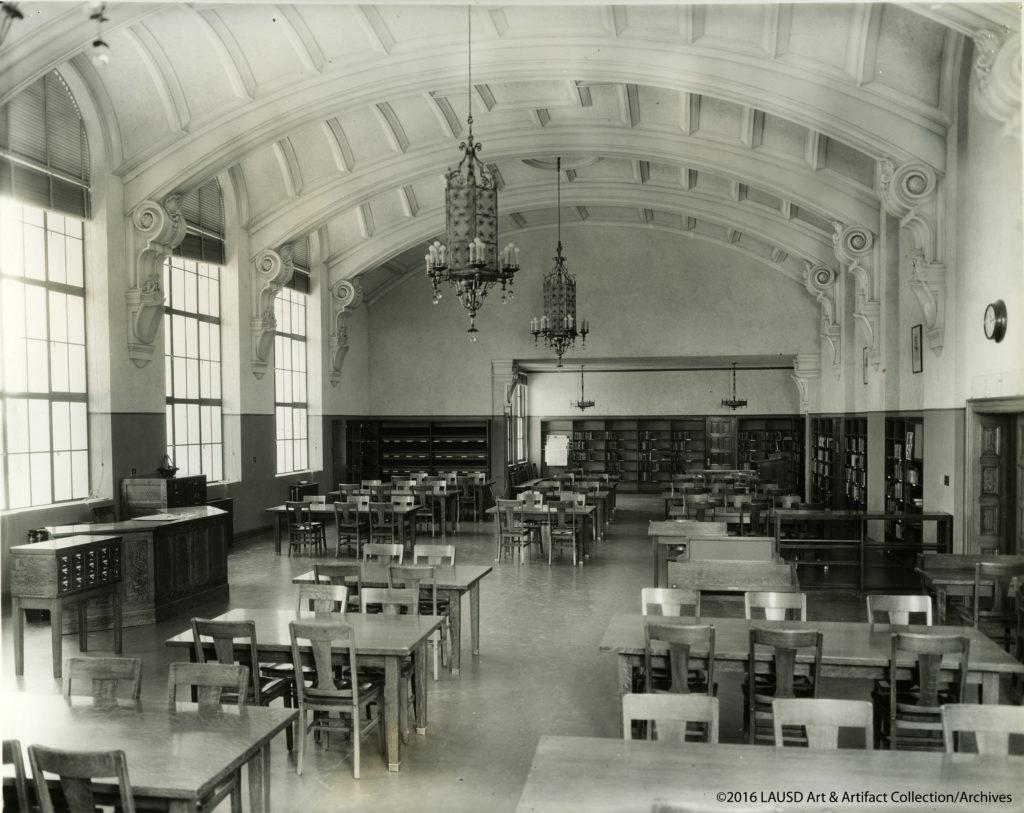

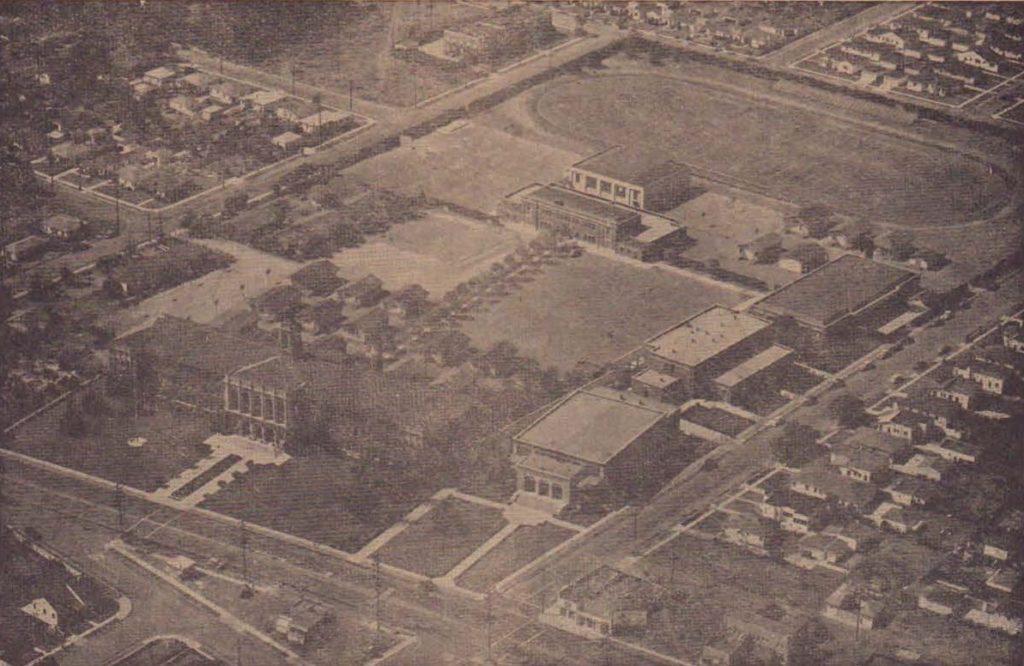

Architects John Corneby Wilson Austin (1870-1963) and Frederic Morse Ashley (1870-1960) designed the structures in the Northern Italian Renaissance style with “multicolored and patterned brickwork, elaborate cast stone decoration, and a bell tower clad in verdigris copper.” (Historic Schools of the Los Angeles Unified School District (March 2002) by Leslie Heumann and Anne Doehne.) They planned it for 1,000 students, allowing for expansion up to 2,500. Building costs were $125,000 for the land, $400,000 for the structures, and $200,000 for equipment.

In May 1931, while Hamilton was under construction, architects Austin and Ashley were selected to design Griffith Observatory. Individually, each had designed a Carnegie library: Austin conceived the Anaheim Public Library (opened 1909), and Ashley drew up Los Angeles’ Arroyo Seco branch library (opened 1914). Together, they had drawn up Monrovia High School (opened 1928 – its front stairs are like Hamilton’s, and it also has a bell tower) and Venice High School‘s Moderne buildings, which were erected between 1935 and 1937. (Venice High’s original structures were demolished due to damage from the 1933 Long Beach earthquake.) Austin designed Los Angeles High School‘s third location (opened 1917; demolished 1971) and the Shrine Auditorium (opened 1926), and he was one of three designers of Los Angeles City Hall (opened January 1, 1928).

Hamilton’s administration building (also including a library, science departments, and 24 classrooms) was named “Brown Hall” in 1981, for William Walker Brown (1894-1967), principal from 1940-1956. Among the athletic fields is Al Michaels Field, a football and track stadium named for alumnus and sportscaster Alan Richard “Al” Michaels. (Michaels met his wife, Linda, in 10th grade at Hamilton.) The west end of the campus includes Los Angeles Department of Water and Power Distribution Station 20 (built in 1933-1934) and Cheviot Hills High School, a continuation school.

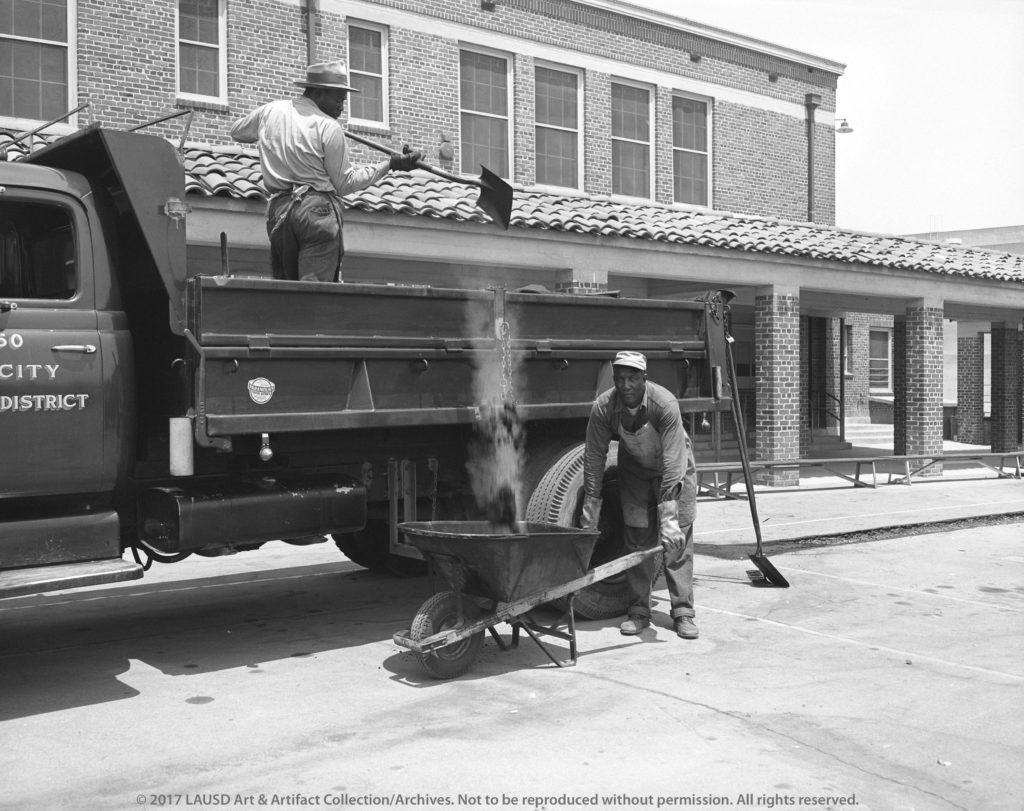

As of 2021, Los Angeles Unified School District was planning a Comprehensive Modernization Project for Alexander Hamilton High School, revamping nearly the entire campus, while preserving Brown Hall and the Norman J. Pattiz Concert Hall.

The proposed Project would address the most critical physical concerns of the buildings and grounds at the campus and, through building replacement, renovation, and modernization, would provide facilities that are safe, secure, and better aligned with the current instructional program. The proposed Project will include the demolition and removal of four permanent buildings/facilities and multiple portable units. Three new permanent buildings will be constructed, along with a central plant and one new lunch shelter to provide for adequate learning spaces and support areas. New athletic fields are also proposed as part of this project. Additional improvements include the modernization of two existing buildings; seismic retrofitting upgrades, access upgrades, and/or additional minor improvements to the other remaining buildings; upgrading and replacing aging utilities and infrastructure; providing new landscaping and hardscaping; and accessibility improvements consistent with the requirements of the Americans with Disabilities Act.

2020 environmental clearance document.

Hamiltonians

A Hamiltonian with History

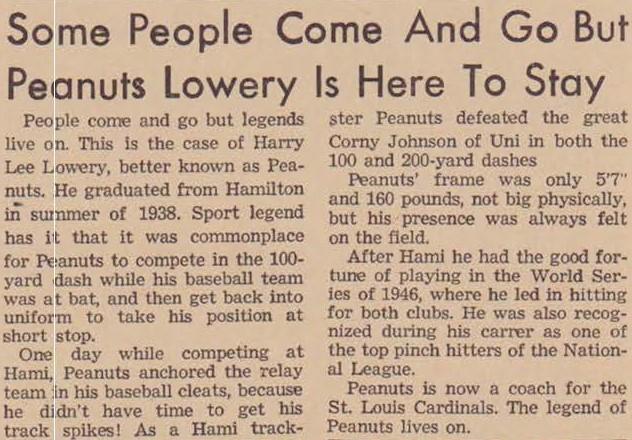

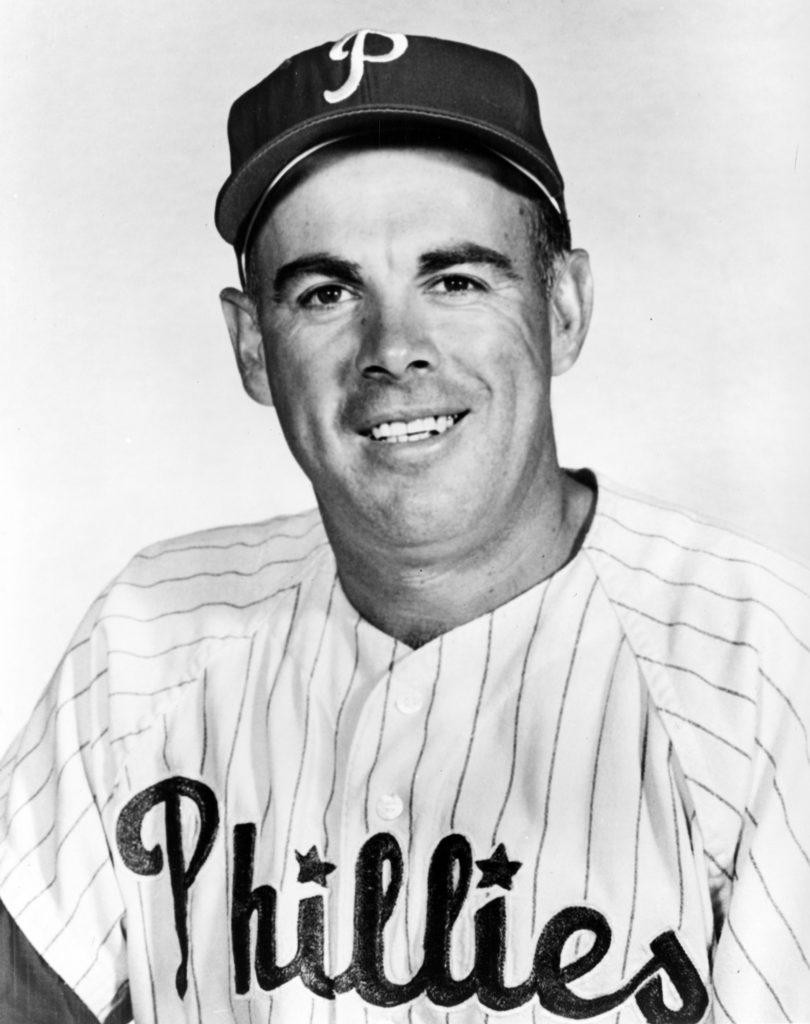

Many of Hamilton’s notable alumni (such as Joel Grey, Airmiess Joseph Asghedom aka Nipsey Hussle (1985-2019), Rita Hayworth (1918-1987), Karen Bass, Gwen Verdon (1925-2000), Lilly Tartikoff, Marc Norman, Norman Joel Pattiz (1943-2022), Michelle Phillips, et al.) are cataloged in the school’s Wikipedia entry. Harry Lee “Peanuts” Lowery (1917-1986) is singled out here because of his local history: he was a great-great-grandson of Jose Ygnacio Antonio Machado (1797-1878), one of four grantees of Rancho La Ballona.

Before advancing to the big leagues (like Hamilton’s star athletes Warren Moon and Sidney Wicks in following generations) Peanut worked in movies. Lowrey grew up by the MGM and Hal Roach movie lots in Culver City. Clark Gable used to have Lowrey keep an eye on his car while he was on the set, and Buster Keaton bought the boy ice cream cones. The “Our Gang” comedies were filmed on location at a farm owned by Lowrey’s grandfather, and he hung out with the cast and filled in as an extra. (RetroSimba, “Cardinals history beyond the box score.”) A Society for American Baseball Research (SABR) biography reports that the “Peanut” nickname came either from the fact that his grandfather described him as “no bigger than a peanut,” or because actress Thelma Todd reportedly gained his good behavior by promising to buy him some peanuts. SABR also tells that, at Hamilton, Lowrey “earned ten letters in baseball, football, and track and field. He ran the 100-yard dash in ten seconds. In his final high-school football game, he scored six touchdowns on runs of 65 yards or more.”

Lowrey played for the Chicago Cubs (1942–43; 1945–49), Cincinnati Reds (1949–50), St. Louis Cardinals (1950–54), and Philadelphia Phillies (1955).” (Wikipedia. He managed in the minor leagues for three seasons, then coached in the majors for 17 years. RetroSimba continues, “Staying true to his roots, Lowrey appeared in some Hollywood baseball movies. According to the Internet Movie Database, he had a credited role playing himself in the 1952 film about Grover Cleveland Alexander, ‘The Winning Team,’ starring Ronald Reagan and Doris Day. Lowrey also had uncredited non-speaking parts in ‘Pride of the Yankees,’ ‘The Stratton Story,’ and ‘The Jackie Robinson Story.'”

Reporting by Hamiltonians

The Federalist newspaper, “Owned by the Student Body of Alexander Hamilton High School, 2955 Robertson Blvd., Los Angeles, California, Published Weekly during the school year by the Journalism Classes,” has been archived by the Hamilton Alumni Association. The papers, from the 1930s through the 1990s, are a trove of history. For instance, The Federalist:

- Profiled World War II refugees attending Hamilton (“Henry Sinosohn and Hans Kalichen [13-year-old Hamilton ninth graders] have not yet learned to take American blessings for granted for their recent memories include hunger, and fear and Nazis’ brutalities.“)

- Commented on the 1960 Nixon-Kennedy presidential debates (“Along with millions of other Americans, we tuned into the much heralded Nixon-Kennedy debates with high expectations; we should have stood in bed.“)

- Covered the Moratorium to End the War in Vietnam (“In response to the deep concern for peace and the nationwide Moratorium movement, on October 15, Hamilton High School conducted a special program that gave concerned students and staff an opportunity to observe this day.“)

- Noted changing generational attitudes (“When my parents and their generation graduated from high school and college they had an unshakeable belief in America and its leaders. …. Now it is 1973 and my generation sees things in a different perspective.“)

Surely, school newspapers nationwide might have done all of that. But what made The Federalist unusual was that many of its stories came from the “Heart of Screenland” (i.e., Culver City). Few other schools could have had a student reporter walk into a Hollywood (actually, Culver City) studio to interview movie star Clark Gable (“Trembling like a leaf, a ‘Federalist’ cub reporter walked into the front office of the Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer Studios. …. ‘Hello, Dorothy, how are you?’ pleasantly inquired Mr. Gable. ‘Scared to death, but otherwise all right,’ I returned.”)

Like Clark Gable had generations before, Steve McQueen granted an interview to The Federalist. In 1979, McQueen, who was notoriously unavailable to the press, came to Hamilton to film The Hunter. The Federalist’s editor-in-chief Rick Penn-Kraus got the one-on-one interview. How big a “get” was it? As Penn-Kraus recounted in 2015, on radio and in print:

First thing Monday morning the calls started coming in to my journalism classroom, starting with legendary publicity mogul Warren Cowan [1927-2008] … who represented McQueen.

“Did you interview Steve McQueen?” he asked me, incredulous. “I’ve got cover stories ready to go at Time, Life, Newsweek, Rolling Stone, and other publications, if McQueen will just sit down with them and do an interview.”

It would be the last interview given by Terrence Stephen “Steve” McQueen (1930–1980).

Reporting about Hamiltonians

The Los Angeles Times’ first article on Hamilton, dated August 3, 1930, was headlined, “High Schools to be Erected – Work Starts on Completion of Final Drawings Spanish Renaissance, Tudor Styles Employed Provisions to be Made for Future Expansion.” (The other school was Los Feliz’ John Marshall High School.) Following are some other L. A. Times articles focusing on the school during some of its more turbulent years. (The Times’ historical archives are available free through the Los Angeles Public Library to those with a library card.)

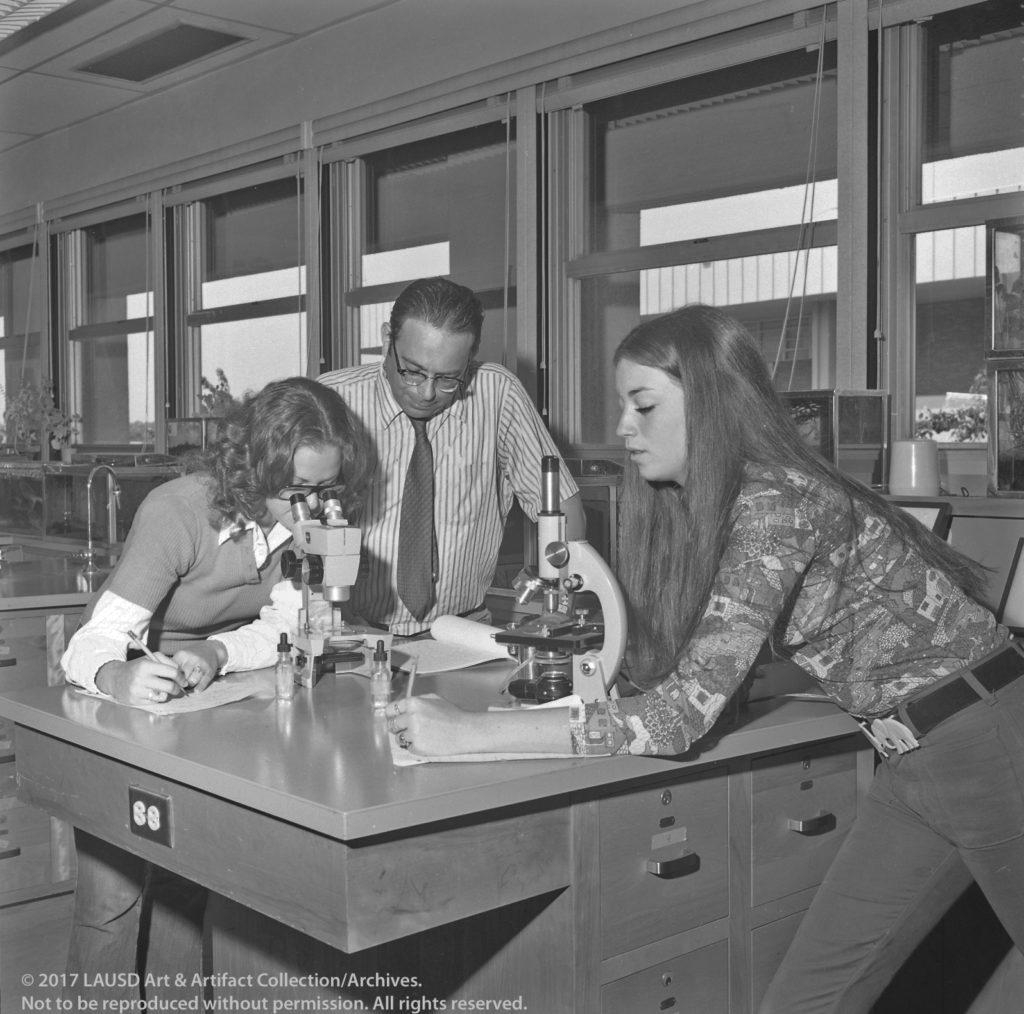

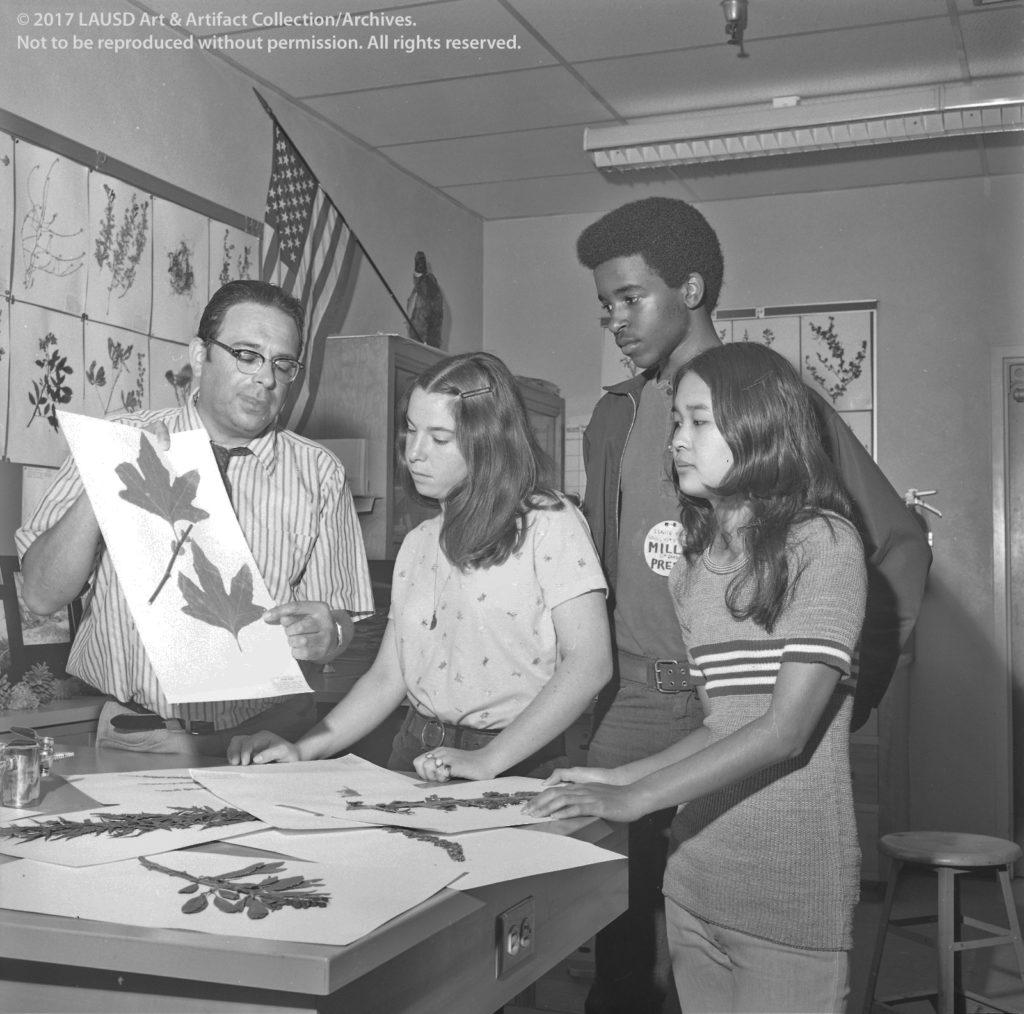

On October 22, 1970, Times staff writer Skip Ferderber called Hamilton “one of the most experimental and exciting schools in the Los Angeles system.”(“Innovations Transform Hamilton High.“) The Los Angeles Unified School District administration, with the freedom given it by California’s 1968 Miller Act, had allowed Hamilton the “flexibility to experiment with classes, curricula and programs.” With physical education cut from 500 to 400 minutes out of 10 school days, and with foreign language requirements reduced, students were given the option of elective classes: “philosophy, anthropology, mass media, Asian and Afro-American history, modern European history and computer math.” During an optional “activity period” at the end of the day, students could study “Japanese culture, American Indian society and culture, chamber music, the ‘Brown Brotherhood’ and the Japanese game of ‘Go.'” There was even a yoga class which “attracted 150 students.”

Mr. Federber detailed other innovations:

Still another experiment is a pilot project set up with the Beverly Hills Bar Assn. and the Langston Law Club, a black law group. Two attorneys, one black and one white, team teach a course in government twice a week discussing selective service, purchasing and installment buying; civic rights and other subjects.

The reporter contrasted that with the Hamilton of 1969, when the new principal, Paul J. Schwartz (c. 1921-1985), had arrived, and looked at the changes his administration had made:

The school was rife with racial antagonism, violence and vandalism were on the upswing and extortion among students was common.

With the idea of getting people talking, Schwartz initiated two convocations earlier this year, one for faculty and students, the other for parents.

The ensuing criticisms and suggestions are the basis for many of the changes at Hamilton today, he said.

Examples include drug programs, a rumor clinic, human relations classes, group counseling and rap sessions, more power for student government, more advance planning, more flexible class scheduling, and more intimate classroom arrangements.

The campus today reflects a happier, healthier and more involved situation for students and faculty alike, Schwartz feels. ….

Mr. Ferderber continued,

Schwartz’s view for Hamilton is into the future when the high school serves the community as a combination community center, family meeting ground, and even a substitute for television. “We’ve got it within our power,” he said, “to utilize this school 24 hours a day and 12 months a year – a real center, the pulse of the community.”

“There’s a real need in urban America for this and I think the school’s the natural vehicle for this kind of operation. You know, a place where kids and parents can come together, something like a cross between the traditional adult school with a regular high school.”

Paul Schwartz was principal for a year and a half before a six-month sabbatical leave in February 1971. (The Federalist, “Bon Voyage, Mr. Schwartz” (Jan. 29, 1971).) In his absence, George Thomas Cole (1925-2019) was principal. Schwartz did not return to Hamilton after his sabbatical; instead, he became a district administrator. (The Federalist; “Mrs. J. Jimenez Named Principal” (June 16, 1971).)

Their successor, Josephine Matilida Casanova Jimenez (1912-2012), had started at Hamilton in 1954 as a foreign language instructor, became the girls’ vice-principal, and would be principal for 15 years before being promoted to oversee 30 Los Angeles high schools. In a biographical video recorded in her 90s, Principal Jimenez recalled, “I was [at Hamilton] for 32 years and I helped the school transition during very, very difficult years of the social, political revolution.” Principal Jimenez shared a story about difficulties Hamilton faced:

One day just out of a clear sky, Paul Schwartz (the principal then) received a phone call followed by a memo that said, “Your schedule is illegal and you’ve got to eliminate it.”

There is a state law that requires 240 minutes of instruction for each student each day. Because of the way the modified schedule worked, Hamilton either undershot or over-shot the 240-minute standard each day. Over each 10-day period, however, everything averaged out according to the state requirement.

But district officials took a strict view of the situation, and said averaging out was not good enough. The new plan had to go. “Aside from the strike,” says Mrs. Jimenez, “that was one of the most demoralizing things that ever happened to the school.”

“The Confusion of Educational Bureaucracy,” L. A. Times, June 14, 1973.

Principal Jimenez’s story was included in the Los Angeles Times‘ five-part series, “The Changing High School,” by education writers Noel Greenwood (1937-2013), Jack McCurdy (c. 1932-2016), and staff writer Celeste Durant. With the principal’s blessing, the reporters spent a cumulative two months at Hamilton High, attending classes and talking with students and teachers.

The Los Angeles Times articles, published on June 10-17, 1983, were headlined:

- Boredom and Tension Replace ‘Golden Age’

- The Students’ Story … Two Views – Dave’s Favorites Are Biology, Tennis and, Mostly, Girls

- The Students’ Story … Two Views – For Dana It’s Books, Boredom, Bells and a Bus Ride Home

- Despite Pressures, Some Good Teaching Does Occur

- Frustration Fills Hamilton High Academic Life

- Poll Shows Areas in Which Teachers, Students Disagree

- Hamilton High Seeks Answers in Black, White

- Optimistic Views Expressed in Poll on Race Relations

- Hamilton High Seeks Security Behind Fences

- Some Glue, a Few Questions – and the Police Come for One Boy

- The Confusion of Educational Bureaucracy

- Principal’s Day Begins on Busy Note – and Then Grows Hectic

- School System, Autonomy Plan Given Low Marks by Teachers

- Education – Weakness and Hope

The final article editorialized, “The story of Hamilton is the story of public education, far short of the goals set for it by society. But it Is a story that Identifies things that can be done to help mediocrity yield to excellence, the excellence already manifest in the work of some teachers in some classes.”

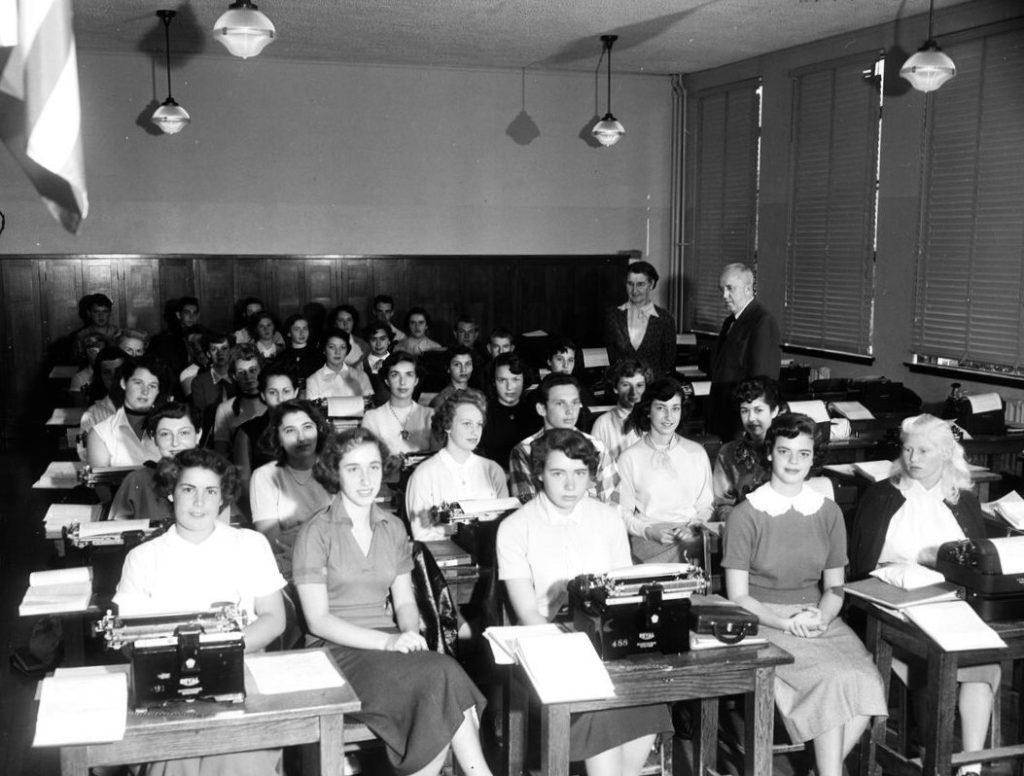

A Teacher’s Perspective (1940)

Anna Mae Mason (1901-1983) began teaching physical education at Hamilton in Fall 1938. She retired at 65 years of age in 1966. In June 1940, Anna submitted her Master’s Thesis: “A Study of the Pupil Personnel of Alexander Hamilton High School of Los Angeles.” Ms. Mason presented on, in her words, “racial and national heritages and native abilities of the pupils, their economic and social backgrounds, their major interests as expressed in their scholastic achievements, their activities outside the school and their home environments.”

She found things mostly “ideal” for students in this new and growing part of Los Angeles’ suburbs:

They live in one-family dwellings, have lived in the district on an average of seven years, the father is regularly employed, the mother is at home, the children either do not find it necessary to work at all or work only occasionally.

She reported that student population included rich and poor, stabilized by the middle class:

The poor are found in the older, more depressed region of Palms, the rich in the recently developed subdivision of Cheviot Hills. A new subdivision, Beverlywood, is at the moment in the process of being developed, and though it is too early to state positively the character it will assume, it is logical to suppose that it will be, as the majority of the district already is, composed of single family residences of the better-than-average type.

And she found racial harmony among the nearly all-White student body:

Racial (and even national) difference from the dominant group in any given situation can be either a greatly adverse or a greatly beneficial phenomenon, the degree of praise or censure to be derived from such difference depending upon the prejudices as to racial (and national) excellence or weakness nurtured by the dominant group. Thus it is usual in groups ruled by Teutonic derivatives, for Europeans to be honored, for Orientals to be tolerated, for Jews and Negroes to be despised.

* * *

Alexander Hamilton High School has a student body that might well be termed “typically American” in respect to language spoken in the home: a vastly dominant nucleus of English-speaking students, a periphery of students differing in speech but similar in race, and a proportionately thinner periphery of students coming from differing racial stock.

Thus, though it might well be that [students coming from differing racial stock] would be faced with a major problem of prejudice, for the student body as a whole no such problem can be said to exist.

With the school “overwhelmingly (97.8 per cent) of homogeneous racial background,” she concluded that “the possibility of racial prejudice exerting any considerable influence in the school would be very slight.”

The tiny fraction of minorities attending Hamilton was unremarkable given that in the more recently developed areas the school served (including Cheviot Hills and Culver City) developers, redlining kept nonwhites from living there unless they were domestic workers in those households.

Under the heading, “Social and Economic Background of the Community,” Mason linked Christianity, morality, and prosperity:

In its measurable attitude toward religious observances, this district again assumes the “average” or “normal” character of the nation as a whole: thirteen Christian denominations offer regular services to the community, supplemented by nine undenominational groups. There is no synagogue in the district.

The correlation between morality and [regular] religious observance is axiomatic, as is also the correlation between morality and a strong middle class.

Anna Mae Mason had a long career at Hamilton, appearing regularly in The Federalist: as a physical education teacher and Philanthropy committee sponsor in 1938, Girls’ Emergency Morale Service (GEMS) faculty sponsor in 1943, Girls’ League sponsor in 1944, Student Court sponsor in 1948, heading girls’ physical education in 1960, and sponsoring the “Lettergirls” in 1965.

Alumni Perspective and Suggestion – What Worked (2016)

In 2016, the Los Angeles Times published an Op-Ed by Hamilton alumni Paul Wallace and Joel Strom (Class of 1972) discussing the tempestuous times and suggesting Hamilton’s past success provided a model to be followed. Their essay included:

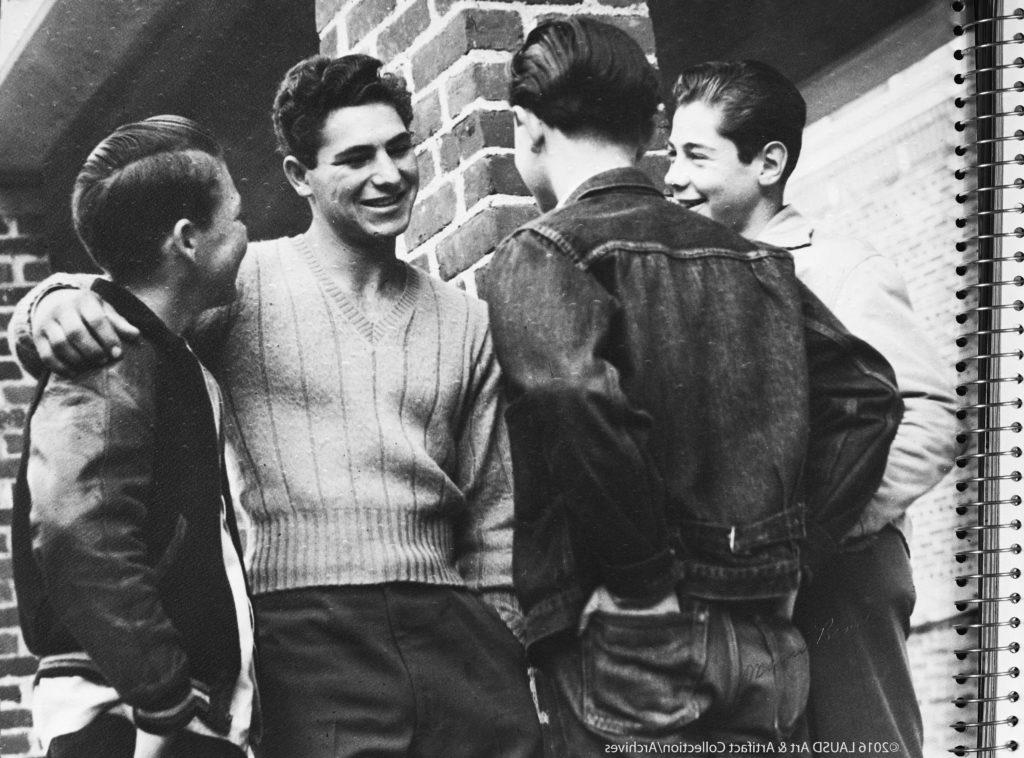

It happened in 1969 when the two of us – one black, one white – ended up at school together as the Los Angeles Unified School District finally began to confront its history of segregation. Race relations in L.A. were tense then. The scars were still fresh from the six-day-long 1965 Watts riots, and at L.A. high schools the races were, for the most part, separated.

[W]e were part of a pilot program of voluntary integration at LAUSD: Project APEX – which stood for Area Program for Enrichment Exchange.

Hamilton, built in 1931, was mostly a white and Jewish school until Project APEX. When the school year started, some white families pulled their children from the school. You could feel the tension — even fear — in the air. The races stayed segregated. It seemed that Hamilton would continue to reflect the divisions that plagued all of L.A.

But the faculty and administration of Hamilton High moved boldly and proactively. Starting in December, they suspended regular academic and extracurricular activities for one day every so often. Instead of going to classes and hanging out with our usual friends, the entire student body met in a “convocation.” We were broken up into multiracial groups of about 30 each; our parents, outside counselors, community leaders and social workers were brought in as facilitators.

The tensions at Hamilton weren’t erased overnight, but everyone knew the “group therapy” helped. The student body wanted the media to tell our story. But no one showed up, so we demonstrated outside the local CBS affiliate. That got attention: black and white students picketing together. A year and a half after the first convocation, the two of us ran for class leadership positions, more or less as a unit. Joel was elected senior class president and Paul was elected student body president, a sign to us of how much had changed.

Now we see the videotapes and follow the investigation of police shootings. We know protesters gather at Los Angeles Police Department news conferences. We hear the chants of Black Lives Matter at campaign rallies. Is racial strife worse now than it was when we were growing up? There is no easy answer to this question, but one thing that was true then is still true today: Direct, personal interaction is the prescription for calming the strife.

Our leaders keep talking about the need for a “national conversation” on race. Let’s start it here, with our children. We’d like to see LAUSD close down all its high schools for a few days this year (and every year), and use the time to hold convocations like the ones we experienced at Hamilton. If we really want to bring people together, then we must do exactly that — bring them together. It worked for the two of us and the hundreds of others who attended Hamilton High with us. It can work again today.

Also worth reading is the L. A. Times’ June 20, 1991, story, “The Music Man: Education: Los Angeles’ youngest principal has transformed Hamilton High with energy, hustle and a knack for getting private business to play his tune” – on how James Goodman “Jim” Berk got Hamilton its Music Academy (which opened in 1987). Berk would be principal from 1989-1992.