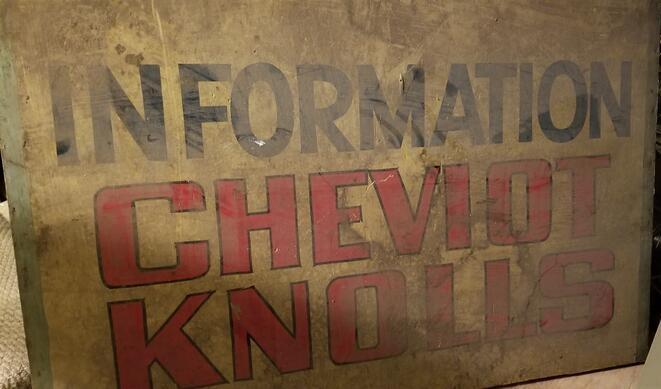

Cheviot Knolls

Harrison, Sweetser & Curtis – subdividers (1886)

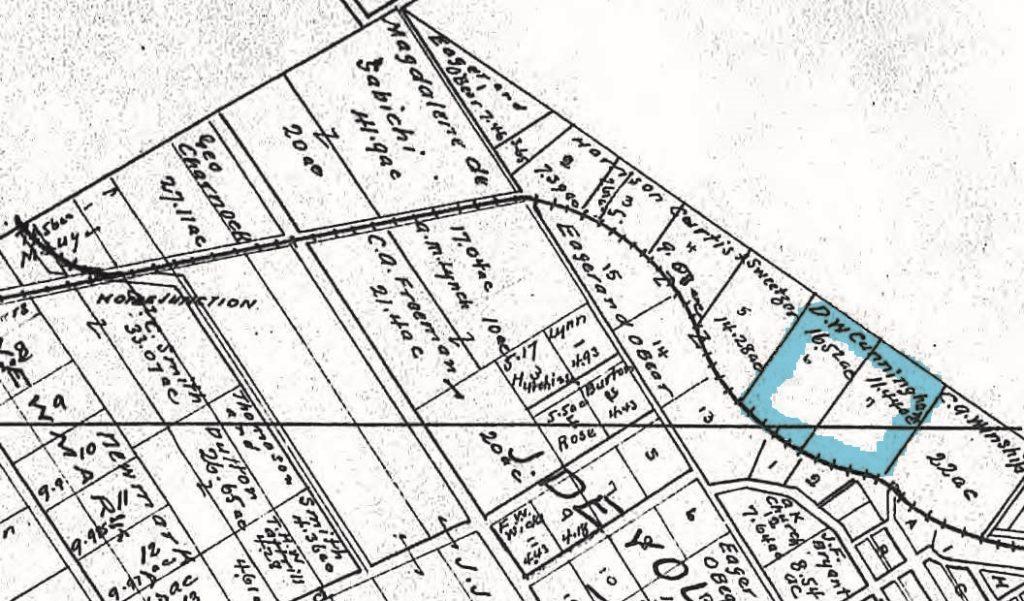

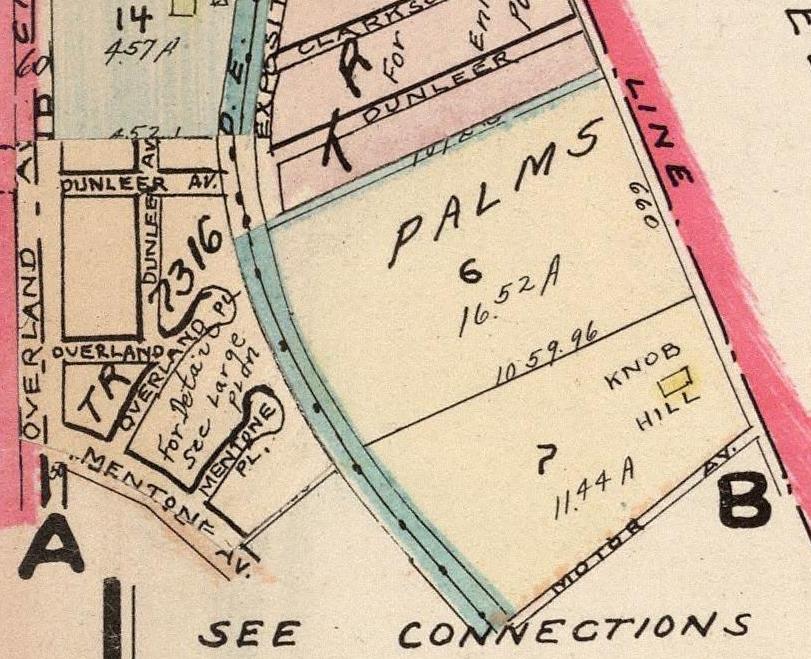

In 1886, Joseph Curtis (1839-1920), Edward Healey Sweetser (1844-1916) and Cornelius Gooding Harrison (1829-1904) bought 500 acres of Rancho La Ballona for $80 an acre (roughly $1.2 million in 2022 dollars) and subdivided it as “The Palms.”

D. W. Cunningham – owner/fruit grower (1894 – 1903)

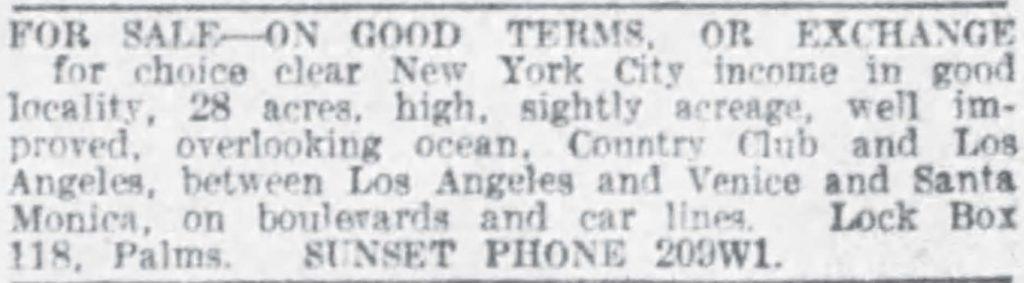

In 1894, David West Cunningham (1829-1916), bought “block 6, and part block 7, The Palms” for $7000 from Curtis and others. A prominent civil engineer who had built waterworks in Massachusetts and the first railroad over the Andes Mountains, he retired to Los Angeles in 1895. In 1897, his daughter Mary F. Rust reportedly bought the land from him for $7000.

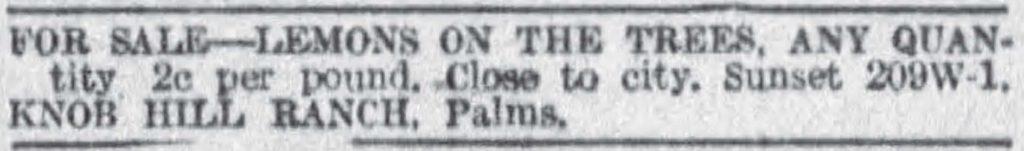

Cunningham grew fruit on the ranch. Local papers reported him sending Eureka lemons to the Los Angeles Chamber of Commerce in 1896 and Royal apricots in 1897. He exhibited Satsuma plums, Kelsey Japan plums, and Royal apricots in liquid at Omaha, Nebraska’s Trans-Mississippi and International Exposition (world’s fair) in 1898.

Agnes D. Terry/Phebe A. Eddy/George Cunningham – owners (1903 – ?)

In May 1903, the Los Angeles Times reported the transfer from “David W Cunningham and Caroline S Cunningham to Agnes D Terry, part blocks 6 and 7, The Palms, $10.” It is unclear why David W. Cunningham would have parted with the property for $10 (or if the number was complete or accurate), but by July 1904, Agnes Terry had sufficient ownership interest to mortgage the property to a George Cunningham: the Times reported that “Agnes D. Terry [conveyed] to George Cunningham. block 6 and part block 7. Palms. 2 years. 7½ per cent, $6000.” The mortgagee, George Cunningham, was apparently not related to David W. Cunningham, since a newspaper called him “young Kentuckian,” and David Cunningham was apparently unconnected to that state. It is unknown whether George Cunningham foreclosed on the mortgage or who subsequent owners were before the Francis Land Company would subdivide it in 1938.

What is clear is that Agnes Daisy Terry (c. 1883-1960) and George Cunningham had a falling out that went to court. According to allegations, George Cunningham was a mining promotor associated with the Hermosa Mining Company who swindled Terry out of $8500 worth of San Diego County real estate in exchange for nearly worthless shares in the mine.

Agnes alleged George Cunningham established himself in her family circle as a close friend and advisor to her mother, Phebe Audrey Eddy (whose married name was Nast then Terry) (c. 1852-1936). Agnes Terry’s mother testified – concerning the Palms property – that she had followed Cunningham’s earlier advice that she mortgage her “place at the Palms,” which was in her daughter Agnes’ name, to pay off the mortgage on the San Diego property.

Agnes and Phebe also made claims against Harry Webster Hanson, Esq. (1872-1929), the lawyer they hired to recover the land from Cunningham, after Hanson was implicated in (and arrested for) a real estate scam involving selling non-existent orange groves in Rialto, California. That swindle was orchestrated by con artist Ollie J. “Oily” Watkins using Watkins’ enterprise, the “California Fruit Growers’ Association.” The suit against Cunningham was delayed while Cunningham recovered from stab wounds he received at the hand of another disgruntled Hermosa Mine investor. The outcome of the lawsuit has not been uncovered.

Phebe A. Eddy (1849-1936) was born about 1849 in New York. She first married Elisha Alvord (1843-1910) from whom she was divorced in 1879. He was from a prominent family and the proceedings were described in several newspaper articles. Phebe and Elisha had 5 children and three lived to marry. Phebe was reputed to have been a very attractive and accomplished woman. She was a skilled dressmaker and lived and worked in Syracuse, Chicago, and then Denver in various retail businesses. In Denver in 1880, she married Augustus Winters Terry (1848–1928) with whom she had five more children. They divorced in 1891. In 1894, in Denver, she married Dr. Henry Highland Nast (1862-1942) under the name Audrey Terry and thereafter she was always known as Audrey. Henry was a physician and a very accomplished musician as well. Henry and Audrey moved to California with her last five children before the 1900 census. Most of her children by Augustus Terry adopted the surname Nast. The family lived in California, mostly in Los Angeles County, for the rest of their lives.

As early as 1913, the land was called “Knob Hill”

Francis Land Company – owner/subdivider (1938)

Cheviot Knolls’ 120 homesites were laid out in December 21, 1938, when the Francis Land Company, an affiliate of the Dominguez Estate Company, resubdivided Block 6 and a portion of Block 7 of The Palms into Tract 11556. The Francis Land Company (1928-1944) was owned and operated by descendants of Juan José Domínguez (1736-1809), recipient of the first Spanish land grant in California, Rancho San Pedro. Rancho San Pedro covered over 120 square miles: today’s Carson, Compton, Gardena, Hermosa Beach, Lomita, Manhattan Beach, Palos Verdes Estates, Rancho Palos Verdes, Redondo Beach, Rolling Hills, Rolling Hills Estates, Torrance, the western portions of Long Beach and Paramount, and the Los Angeles communities of Harbor City, Harbor Gateway, San Pedro, Terminal Island and Wilmington. The Francis Land Company’s namesake, Maria de los Reyes Domínguez de Francis (1847-1933) (“Reyes Francis”), was the youngest granddaughter of Juan José Domínguez’ brother, Cristóbal Domínguez (1761-1822). Cristóbal had inherited half of Rancho San Pedro and bequeathed it to his six surviving children, among them Luis Gonzaga Policarpo Manuel Antonio Fernando Dominguez y Reyes (1803-1882) – Reyes Francis’ father.

Land holdings aside, Reyes Francis became “substantially wealthier” when oil was found beneath her Dominguez Hill holdings. Widowed, she engaged family friend and attorney Henry O’Melveny to formed the Francis Land Company.

Due to her immense wealth, she had to pay more income taxes than any other woman in the United States. At the time of her death on June 4, 1933, her estate was worth $15,000,000.

Historic Adobes of Los Angeles County, Rancho San Pedro, The Dominguez Ranch Adobe (1997) by John R. Kielbasa.

Reyes Francis’ nephew, David V. Carson, led the Francis Land Company when Cheviot Knolls was developed a few years after her death. (California Legacy, The Watson Family, by Judson A. Grenier, pp. 414-415.) In 1939-1940, Ramona Properties, owned by Reyes Francis’ sister Dolores Watson Jarrett’s heirs, purchased Cheviot Knolls lots from the Francis Land Company. (Description of Inventory of the Rancho San Pedro Collection, 1769-1972, bulk 1900-1960, California State University, Dominguez Hills, Archives and Special Collections Department.)

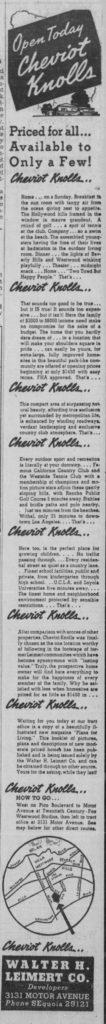

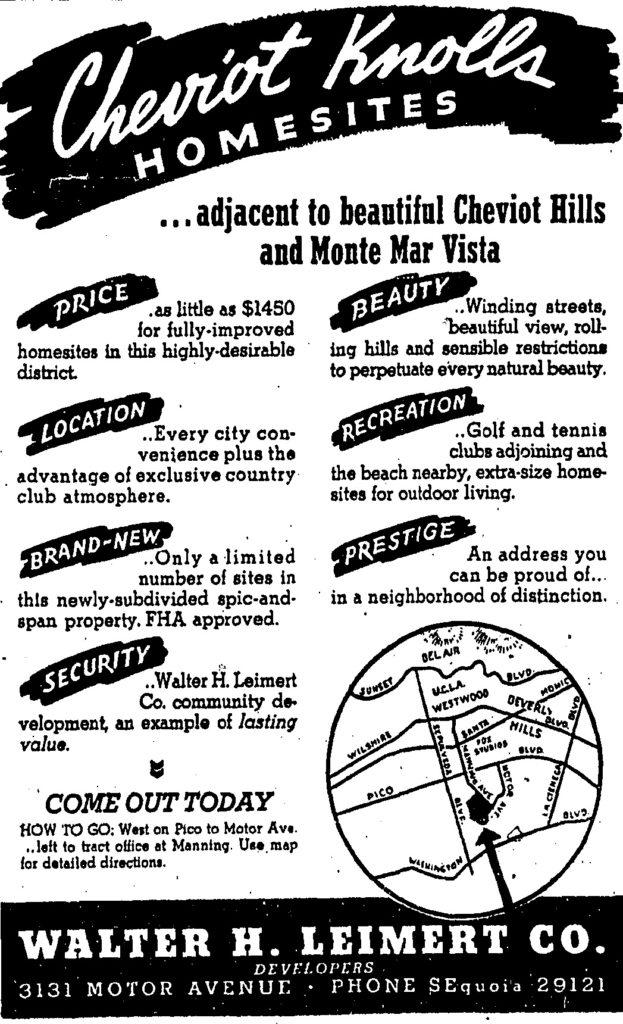

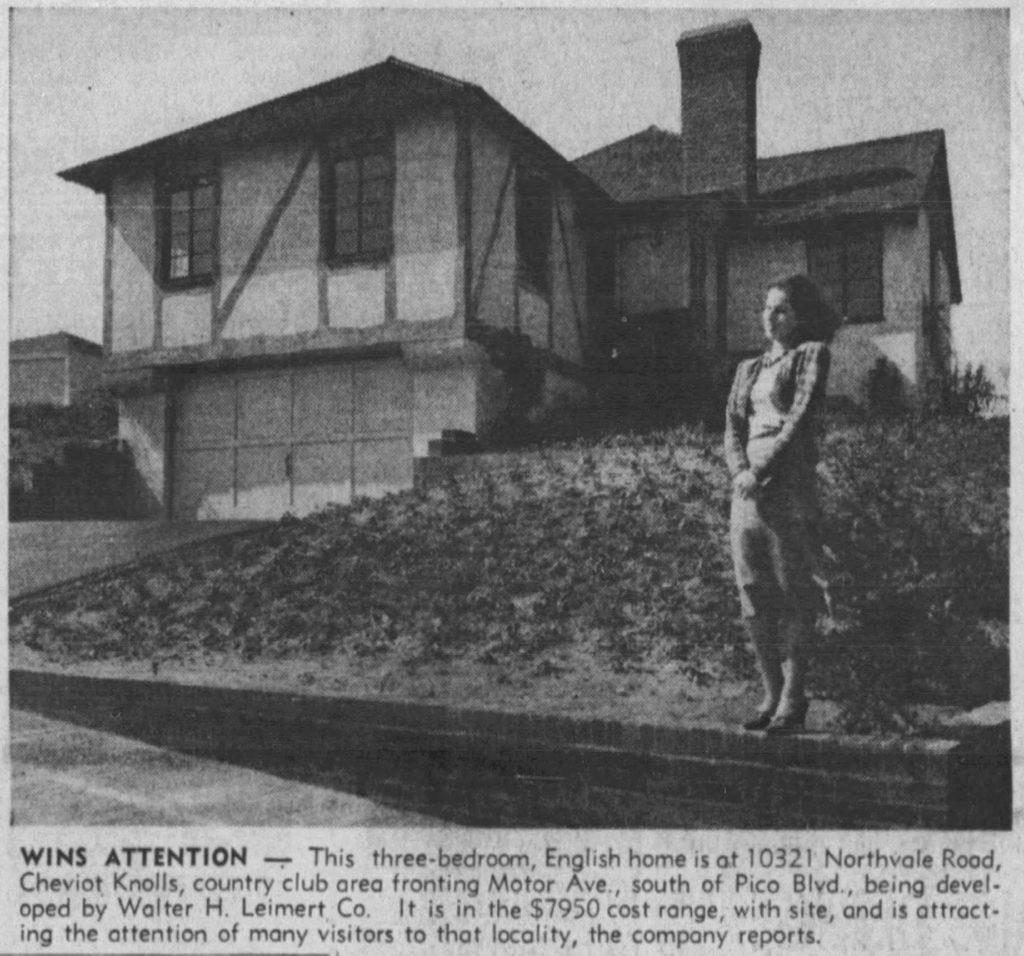

Walter H. Leimert Company – developer

The Walter H. Leimert Company, run by Walter H. Leimert (1887-1970), developed Cheviot Knolls for the Francis Land Company. Today, Leimert is better known for the Leimert Park subdivision. The Leimert provenance was a selling point: Cheviot Knolls was advertised as “following in the footsteps of former Leimert communities which have become synonymous with ‘lasting value.’” The senior Leimert worked with his son, Walter “Tim” Leimert Jr. (1921-2004), to develop Beverlywood, east of Cheviot Hills, for the Beverly-Arnaz Land Company, which involved another Dominguez family corporation.

The City imposed pages of requirements when it approved Tract 11556. For instance, storm drain and sewer easements were required, including under the “future street” between Northvale Road and the Southern Pacific Railroad Right of Way. (Exposition Boulevard ran up to the tract’s western edge in the adjacent County Club Highlands subdivision, Tract 7156.) The City prohibited “the fronting of houses on the ‘future’ Exposition Boulevard,” while it required that houses with backyards along Exposition “present a pleasing appearance … in substantial conformity to the fronts of said houses.”

In 1951, the developer deeded Lots 121 and 122 for the future Exposition Boulevard to the City. It was never built. As of 2022, the City was dedicating the land to a bike path.

Neff & Hurst – realtor

When Cheviot Knolls came on the market in 1939, realtors Neff & Hurst, at 3131 Motor Avenue, were the exclusive selling agents. The City Council passed an ordinance allowing Francis Land Company to locate its real estate office on that residential lot, now 10300 Northvale Avenue, the eastern entrance to the tract, for two years. (Neff & Hurst had previously offered the Cheviot Hills tract from their 3017 Motor Avenue office up the street.) As sales got underway, “Realty activity in the Cheviot Knolls-Cheviot Hills-Monte Mar Vista residential district . . . was given marked impetus . . . through announcement of . . . the new $12,000,000 Paramount Studios on a near-by site.” “Paramount City,” Paramount Studios’ planned new plant west of Cheviot Hills, was never built, although other nearby studios remained in the picture.

In 1940, a Cheviot Knolls view lot was advertised at $1,125, and a “California ranch-style home – two bedrooms and den – 1 1/2 baths – tile kitchen – large walled-in rear porch” was priced at $7,250. Like other neighborhood tracts, Cheviot Knolls was advertised as restricted.

Protected by “Sensible Restrictions” and “F. H. A. Approved”

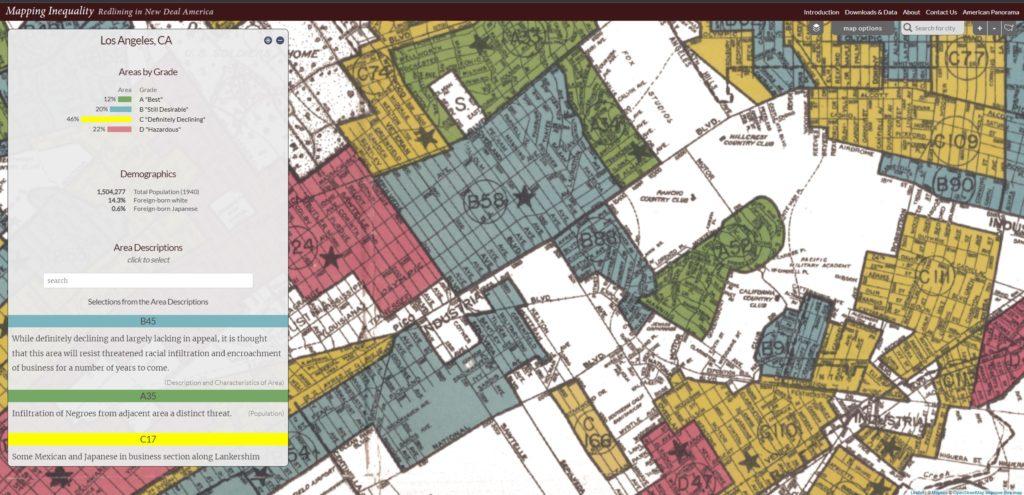

Maybe advertising homes as “protected by sensible restrictions” or “highly restricted” or “well restricted” was meant to highlight the prohibition against alcohol sales in Cheviot Knolls, where owners agreed that “no part of said realty shall ever at any time be used for the purpose of buying, selling, or handling intoxicating liquors.” The Palms had a similar restriction: “Deeds contain a forfeiture clause prohibiting the sale of spiritous liquors.” But since Cheviot Knolls was only residential, it is more likely that the touted restriction was code for “Whites Only.” Indeed, only the latter restriction was essential to the development of Cheviot Knolls, as explained by California State University Dominguez Hills University Library archivist, Thomas Philo in “Perpetual and Binding Forever: Race and the Creation of a Los Angeles Subdivision” (2021).

Mr. Philo focuses on Cheviot Knolls to illustrate the interplay between corporate and governmental racism in the 20th century housing industry. Essentially, the Cheviot Knolls subdivision required the Federal Housing Administration’s approval to secure mortgage insurance, the FHA did not approve of racial mixing, and the FHA’s requirements were satisfied by Leimert Company restricting Cheviot Knolls to “persons whose blood [was] entirely that of the Caucasian race.”

Attorney Stanley L. McMichael (1879-1950) laid bare the self-fulfilling prophesy that integration lowered property values in his book, Real Estate Subdivisions, published in 1949, just after the Supreme Court stopped courts from enforcing restrictive covenants with its decision in Shelley v. Kraemer (1948) 334 US 1.

That the entry of non-Caucasians into districts where distinctly Caucasian residents live tends to depress real estate values is agreed to by practically all real estate subdividers and students of city life and growth. Infiltration at the outset may be slow, but once the trend is established, values start to drop, until properties can be purchased at discounts of from 50 to 75 per cent. Later, when a district has been entirely taken over, values tend to re-establish themselves to meet the needs and demands of the new occupants.

Stanley L. McMichael, Real Estate Subdivisions (New York: Prentice-Hall, Inc. 1949), chapter 22 (Racial Restrictions), p. 204.

Fear that property values would go down caused White flight, which lowered property values temporarily. McMichael’s book was a how-to on keeping things from changing to – as he saw it – protect property values. That included laying out the case for a Constitutional Amendment proposed by Philip M. Rea, president of the Los Angeles Realty Board, to retroactively reverse Shelley v. Kraemer.

Additionally, the insistence of some Negroes upon moving into areas previously restricted exclusively to the occupancy of Caucasians will necessarily create racial tensions and antagonisms and do much harm to our national social structure.

To avoid these consequences and to stabilize the values of home ownership, it has become essential that an amendment be adopted to the Constitution of the United States, as herein proposed. This amendment should be made retroactive, so as to provide a remedy for those who have already suffered from the conditions mentioned. In the interests of fairness it should be so drawn as to assure Negroes of the enjoyment of areas restricted to the occupancy of their race, as well as to insure Caucasians of the enjoyment of areas restricted to the occupancy of Caucasians.

Stanley L. McMichael, Real Estate Subdivisions (New York: Prentice-Hall, Inc. 1949), chapter 22 (Racial Restrictions), pp. 204 – 206.

Attorney McMichael’s racist perspective inherent in his guide to developers and their lawyers was not unique. Indeed, the University of Miami Law Review summarized the book uncritically:

Can a subdivider of land so restrict sales of his lots that he can prevent, legally, the occupancy of such by non-Caucasians?” is a question McMichael covers at length [in Real Estate Subdivisions]. …. Regarding these decisions rendered by the Supreme Court, McMichael lists eight suggestions “made to soften the impact of the blow that racial restrictions have received.”

Gary I. Salzman, 5 U. Miami L. Rev. 185 (1950).

Mr. McMichael is quoted here because of his affiliation with Cheviot Knolls’ developer, Walter H. Leimert, whose “typical set of restrictions controlling the development of a medium -grade subdivision known as ‘Beverlywood’ in the city of Los Angeles, California” are reprinted in McMichael’s book “through the courtesy of Walter H. Leimert, developer.” (Real Estate Subdivisions, p. 345.)

As World War II was coming closer to an end, lots were once again advertised. Reflecting rationing, one ad stated the “lots are ready for home construction as soon as materials are available.”