Cheviot Hills’ (often renamed & mostly tennis) Club

The first tennis would be played at the Palomar Tennis Club on August 16, 1925, per a Los Angeles Times article. The paper reported that the club, at 3084 Motor Avenue in the southeast corner of the Cheviot Hills subdivision, was still under construction: “The Palomar Tennis Club’s first two courts will be thrown open for use tomorrow morning, according to an announcement yesterday by Rans Abbott, manager or that organization. The courts were finished last week, but have been given additional time to set. The exhibition and championship courts are the ones that are finished.”

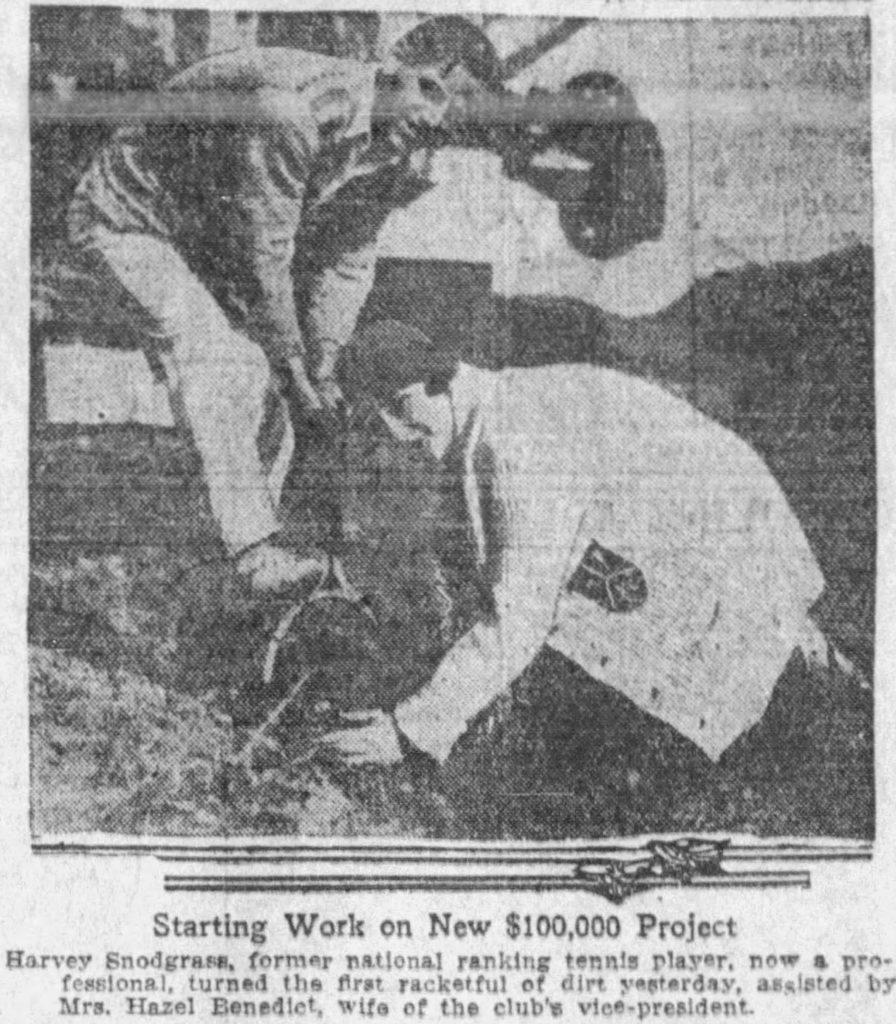

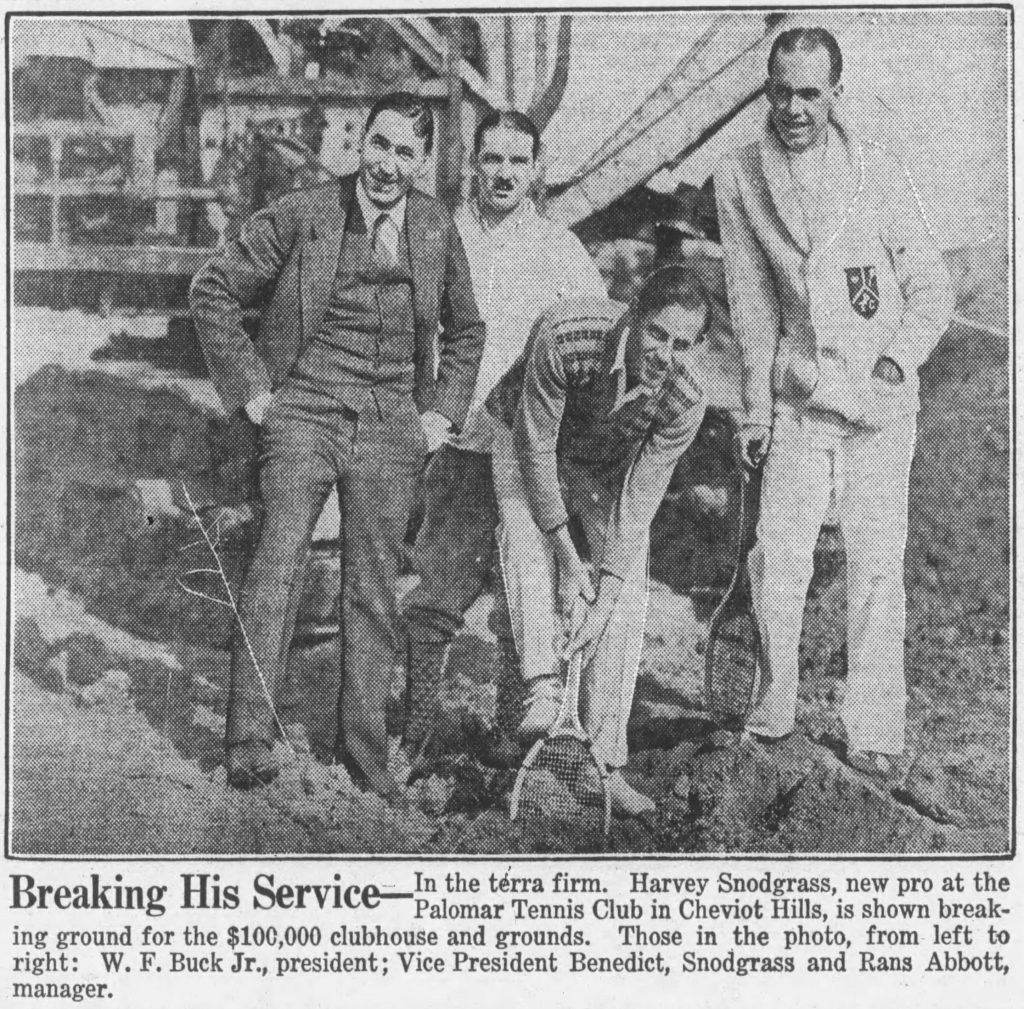

Nearly six months later the Times covered the groundbreaking for the “new $100,000 Palomar Tennis clubhouse and swimming pool at Cheviot Hills near the California Country Club.” Harvey Burton Snodgrass (1896-1983) “turned the first racketfull of dirt … assisted by Mrs. Hazel Benedict, wife of the club’s vice president.” The design would be “true Spanish, very low and long.” (L. A. Times, Jan. 25, 1926.)

The following January, as construction continued, a report said that recently “ground was broken for the clubhouse of the Palomar Tennis Club, which has just purchased six acres at Cheviot Hills.” (L. A. Evening Express, Jan. 30, 1926.)

Although the above article quoted “Harvey Nelson of Franz Nelson & Sons, developers of Cheviot Hills” and featured a picture of club pro Harvey Snodgrass congratulating club president William Franklin “W. F.” Buck (1896-1944), it left out Buck’s connection to the developers. In fact, W. F. Buck, was a Nelson family member. Buck had married Bernice Ethelda Nelson (1896-1991) in Nebraska in 1920, before the families moved west.

So, the Palomar Club was essentially part of the Cheviot Hills development, with the Nelsons nearby: William and Bernice resided at 10275 Dunleer Drive in 1931, two blocks from the club. (Before passing away in 1924, Bernice’s brother George had begun building a house a block closer at 3053 Motor Avenue, which may have stayed in the family.) Frans Nelson tells it this way in his biography: “We also built a clubhouse near the properties complete with plunge and tennis courts.” And, in his obituary, Frans Nelson was remembered for founding the club:

After his retirement, he came to California, only to become so enthusiastic over real estate development that he re-entered business, sponsoring the tract now known as Cheviot Hills and building and organizing the Palomar Tennis Club, now known as the West Side Club. He was also one of the founders of the California Country Club.

Apocryphal Origin Story

As early as 2013 the club, then known as the Beverly Hills Country Club, claimed it was started by Elmer Griffin.

The Club’s fabled story begins with Elmer Griffin. In 1926, Griffin opened the Westside Tennis Club, as a club for actors and entertainers who were shunned by the elite clubs of the time. The Club became a special gathering place some of Hollywood’s most famous actors of the time, including Humphrey Bogart, Errol Flynn, Caesar Romero and Joan Bennett. Over the last 90 years, the Club has changed names and changed hands a number of times, but has never lost its inherent appeal to the residents of Los Angeles.

Beverly Hills Country Club website (archived by the Internet Archive Wayback Machine).

“Fabled” is an appropriate adjective for the club’s origin story since nothing in the contemporaneous history of its opening connects it to Elmer Griffin. And Griffin’s connection would have been touted, given his celebrity in the 1920s. Indeed, he was one of three Griffin Brothers – Clarence James Griffin (1888-1973), Elmer John Griffin (1896-1980), and Mervyn Edward Griffin (1901-1956) – who were well-known tennis players in the 1920s. For instance, the 1920 California tennis rankings had Clarence in second place; Mervyn in sixth; and Elmer in ninth. Each is in the United States Tennis Association Northern California Hall of Fame. (Robert Lindley Murray: the Reluctant U. S. Tennis Champion, Roger W. Ohnsong (2011) p. 77.)

In 1926, Elmer Griffin was not starting up a tennis club in Los Angeles; instead, he was living in New York City. In April 1930, the New York Times reported Helen Wills-Moody’s triumph over “veteran Elmer Griffin … who now lives in New York. Griffin … first played against Mrs. Moody in 1917, and since coming to New York four years ago has been the first every year to oppose her in exhibitions here.” (Thus, Griffin moved to New York City in 1926.)

Elmer Griffin’s only apparent connection to the Cheviot Hills club is that he played there. For instance, in 1935, he played up-and-comer Bobby Riggs (1918-1995).

Bobby Riggs, 18-year-old Franklin High School boy, seeks his second local tennis crown in two days this afternoon when he plays Elmer Griffin for the county singles championship on the court of the Bath and Tennis Club in Cheviot Hills.

December 8, 1935, L. A. Times.

Riggs was crowned Southern California interscholastic titlist yesterday at Fullerton. He is the national junior champion. Griffin, twenty-two years older than his foe, won the California State singles crown fifteen years ago.

Griffin and Riggs share another connection: decades apart they would engage in tennis matches against top women’s players. As the above April 1930 New York Times article shows, Griffin was playing exhibition matches against Helen Wills-Moody –decades before Riggs did it in the sensational 1973 “Battle of the Sexes” match versus Billy Jean King. Incidentally, in 1933, Helen Wills beat another man, eighth-ranked American male player Phil Neer, who, in 1930, also swung a racket at the Cheviot club.

In any event, in 2017, the club changed its name from “Beverly Hills Country Club” to “Griffin Club,” perpetuating the fable:

The Club was established by the late Elmer Griffin, uncle of celebrity businessman Merv Griffin, as a place where Twentieth Century Fox and MGM executives could meet, socialize, conduct business and play tennis. During the early years of operation, when many other area clubs were not admitting entertainers, many sports and socially minded celebrities joined the Club. The Club quickly became a haven for film industry personalities and entertainers as a favorite place to play tennis, and to see and be seen. Early Members included Cesar Romero, Humphrey Bogart, Errol Flynn, Ann Sothern, Jack Lemmon, Edie Adams, Ernie Kovacs, Robert Montgomery and Oscar Hammerstein to name a few. Although the Membership at Beverly Hills Country Club is now more diverse, the Club’s Membership still includes top celebrities, athletes and executives.

Griffin Club website.

The Club’s Many Names

Palomar Tennis Club (August 16, 1925-1932)

Ransford “Rans” James Abbott (1898-1956) was the sales manager/manager of the Palomar Tennis Club when he announced the first two courts would be open for play the next day. (L. A. Times, Aug. 15, 1925.) In the January 3, 1926, L. A. Times, W. F. Buck (aka W. F. Buck, Jr.) was called the “newly elected president of the club.” Buck confirmed the “report that Harvey Snodgrass, nationally famous tennis player and sixth ranking national player, will have the position of tennis professional exclusively for the Palomar Tennis Club.” Buck said “three classes of courts will be constructed: clay, cement and gravel. The exhibition court grand stand will seat 3500 spectators.” Others named were Maynard G. Benedict, vice-president and B. F. Bressler, secretary and treasurer. Snodgrass was “1925 national clay court tennis champion in doubles.” (San Bernardino Daily Sun, Feb. 15, 1926.)

At the Palomar club, Snodgrass used the “slow speed motion picture camera as a short cut in tennis coaching.” “A photographer on the sidelines ‘shoots’ the pupils as they go through their first few lessons. Then they are shown the film and all ‘defects’ in playing form are pointed out. Then back to the courts they go for correction.” (San Bernardino Daily Sun, Feb. 28, 1926.)

On October 27, 1926, the Los Angeles Times reported the clubhouse’s upcoming November 15th unveiling. It had been furnished by renowned interior decorator Howard Verbeck (1891-1959)

In April 1927, the club hosted whippet racing. (L. A. Times, March 27, 1927.) Cheviot Hills subdivider, Frans Nelson (who lived up the street), using the event to promote home sales, put up the purse.

By December 1928, William (Bill) Coit Ackerman (1902-1988) had “succeeded Harvey Snodgrass as instructor at the Palomar tennis club.” (San Bernardino Daily Sun, Dec. 20, 1928.) In 1921, Ackerman, then a sophomore, became UCLA’s tennis coach. He brought the school its first NCAA championship of any sort (in 1950) and was inducted into the NCAA Hall of Fame in 1984. He is the namesake of the student union building, Ackerman Union. (L. A. Times, May 17, 1984; L. A. Times, Feb. 17, 1988.) In 1919, Ackerman was in the first class at the University of California’s Southern Branch (then on Vermont Avenue, the current site of Los Angeles City College). Reportedly (and coincidentally) his father surveyed John Wolfskill’s Rancho San Jose de Buenos Ayres, where UCLA would relocate in 1929.

Later in 1927, the club added stables and bought six thoroughbreds to provide horseback riding for its members. (L. A. Times, Sept. 25, 1927.)

Pacific Coast Tennis Club (1932-1933)

On December 8, 1932, the Los Angeles Times reported that “The name of the Palomar Tennis Club has been changed to the Pacific Coast Tennis Club.” Art Park was the “professional in charge.”

Palomar-Pacific Club (1933)

The Palomar-Pacific Club ran into trouble with the vice squad near the end of Prohibition – and not just for booze. In July 1933, fourteen were arrested on “various charges of gambling when Acting Captain of Detectives Sears, and his newly depleted Central vice squad raided the Palomar-Pacific Club ….” He told the press, “in these places you can get the finest imported liquors in all kinds of fancy pre-prohibition drinks.” (L. A. Times, July 8, 1933.) “At the time of the raid police officers reported finding a roulette wheel, crap tables and other gambling devices in operation.” Only one of those arrested showed up for the first date set for trial, one Joseph Hanahan. Bench warrants were issued for the rest. (L. A. Times, Aug. 5, 1933.)

Colony Club (1933-1934)

On December 12, 1933, Colony Club manager S. Stanford Stickney and his attorney David Clark issued a “joint statement” resulting from a “complaint by the building and safety department that the establishment had failed to obtain a permit for certain alterations to the structure.” “The Colony Club is closed and will remain closed, as far as we are concerned and we are turning in our lease!” (Post Record newspaper.)

A week earlier, December 5, 1933, the Eighteenth Amendment had repealed the Twenty-first Amendment, and alcohol was once more legal. In California, alcohol sales were covered by new rules: California’s State Liquor Control Act. The Colony Club was among 32 “clubs” that the State Board of Equalization denied the right to sell pending a “proper showing.” (L. A. Times, Jan. 13, 1934.) “Most places which were denied the privilege of selling beer and wines were listed as clubs and, generally, the board found that they were not truly clubs. In seeking renewals, the proprietors [were] obliged to show that their quarters [were] open to the public and that they compl[ied] fully with the law in other respects.” The Colony Club was one of four listed as “widely known to the public.”

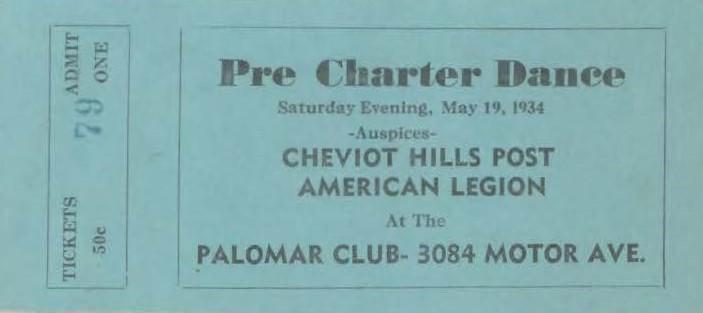

Palomar Tennis Club (1934)

Apparently, the club used its original name again during this tumultuous year.

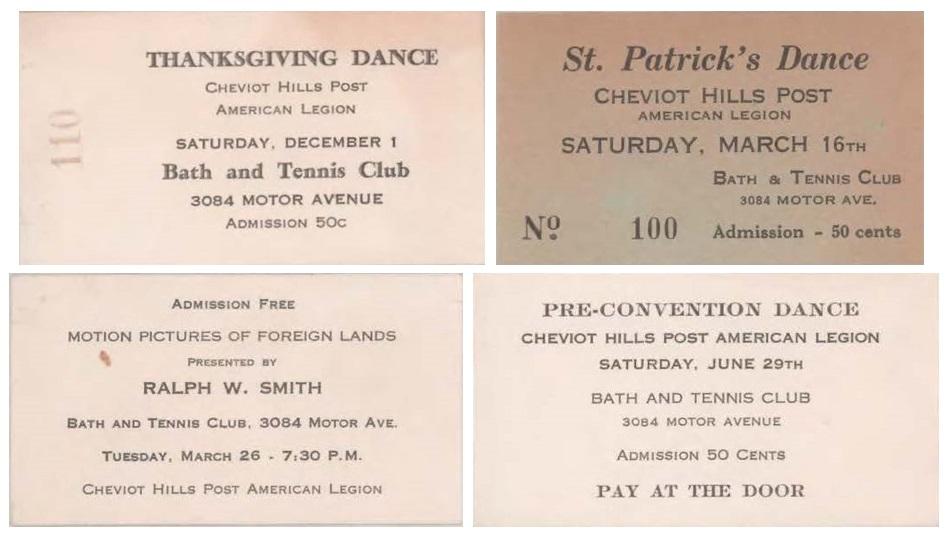

Bath and Tennis Club (1934-1935)

In 1934, Harvey Snodgrass was once again tennis pro at the club, which was now owned by a celebrity. The “Bath and Tennis Club, fashioned after the Long Island Club of the same name in the East. Nick Stuart, film actor, is president of the local club.” At the time, the club featured “eight tennis courts, badminton and squash courts, a ninety by thirty-foot swimming pool, indoor sports, electric cabinet baths, health ray treatments and all the latest scientific conveniences.” (L. A. Times, June 5, 1934.)

Later that year, sixteen-year-old Bobby Riggs played at the club, losing to Gene Mako (1916-2013) who “all but sweep his youthful opponent off the court.” (L. A. Times, Dec. 24, 1934.) Riggs played there again in 1935. (L. A. Times, Nov. 28, 1935; L. A. Times, Dec. 8, 1935.) In 1939, Riggs won Wimbledon and U. S. National Championships (now the U. S. Open).

West Side Tennis Club (1936-1954)

In 1936, the Los Angeles Times reported:

West Side Tennis Club will initiate the outdoor swimming season with a pre-Olympic review of local champions at the opening of its pool in Cheviot Hills this afternoon at 2 o’clock. This is the first of sixteen outdoor meets already sanctioned by the Southern Pacific Association A.A.U., according to C. P. L. Nichols, chairman of the swimming committee.

For this afternoon’s program Fred Cady, Olympic diving coach for the Berlin Games, has a choice selection of Olympic prospects, headed by 13-year-old Marjorie Gestring who stunned gray heads of the swimming world by her recent barnstorming debut at the Chicago indoor nationals championships last month.

At the age of 13 years and 268 days, Marjorie Gestring won the gold medal in 3-meter springboard diving at the 1936 Summer Olympics in Berlin, making her, at the time, the youngest person ever to win an Olympic gold medal.

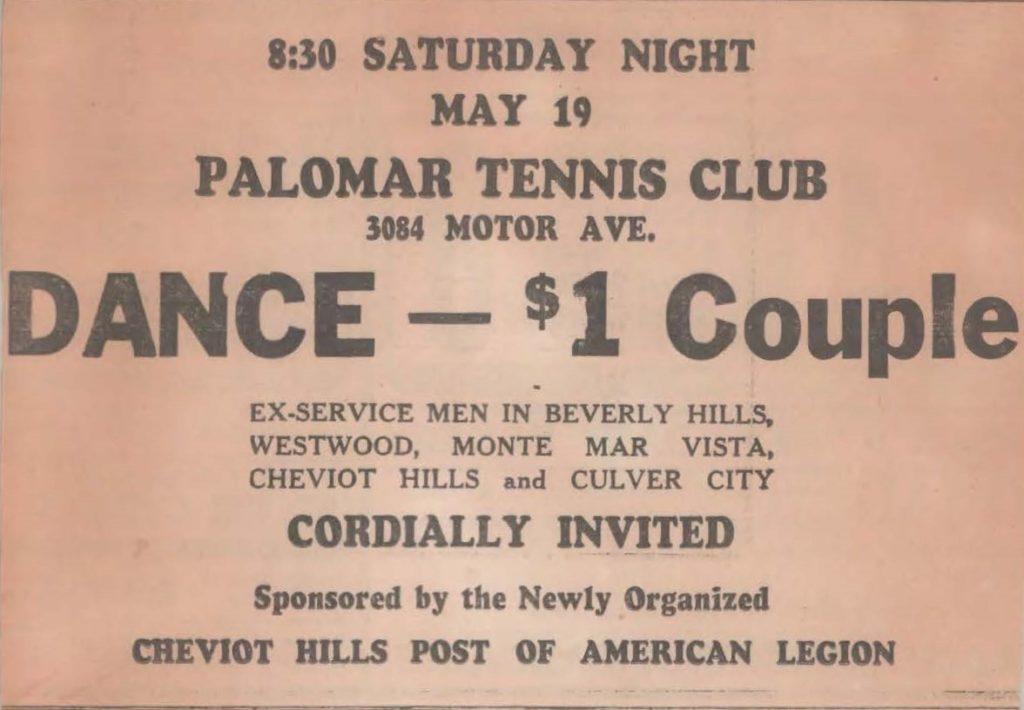

In 1937, the Cheviot Hills Garden Club was meeting at the “West Side Tennis Club.” (Garden Club History 1937.) It was still meeting there in 1950 (L. A. Times, Jan. 5, 1950) and into the 1970s (L. A. Times, Nov. 9, 1972). Indeed, many area groups (such as the American Legion, Palms Chamber of Commerce, and the Beverly Hills Republican Club) have gathered at the site.

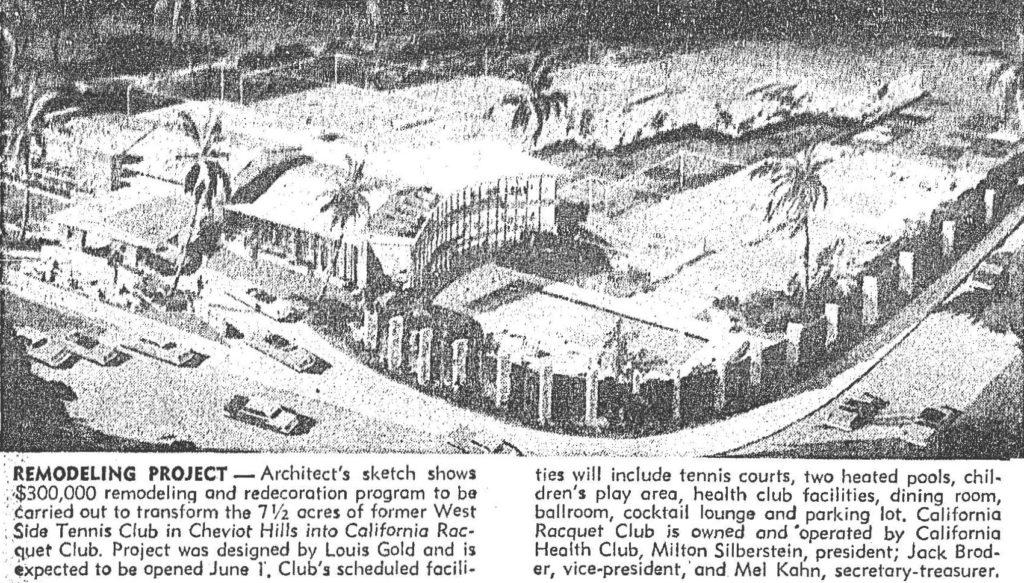

California Racquet Club (1955-1962)

In 1955, the Los Angeles Times featured an architect’s sketch (below) of the Louis Gold-designed “remodeling and redecoration program to be carried out to transform the 7½ acres of former West Side Tennis Club in Cheviot Hills into California Racquet Club.” The redo, set to open June 1st, was to include “tennis courts, two heated pools, children’s play area, health club facilities, dining room, ballroom, cocktail lounge and parking lot.” The California Racquet Club was “owned and operated by California Health Club, Milton Silberstein, president; Jack Broder, vice-president; and Mel Kahn, secretary-treasurer.”

Standard Club (1962-1971)

This December 31, 1964, Los Angeles Times report has the wrong address and city (albeit newspapers have long referred to the area as Culver City). But the list of celebrity owners and former owners is consistent with other sources – and includes a foretaste of animosity from neighbors:

Owners of 13 Culver City homes have filed suit in Superior Court against a nearby tennis club, charging it made too much noise, and have asked an injunction to prevent further club operation until it had “toned down” its facilities.

The suit was filed against the owners and managers of the Standard Club, formerly the California Racquet Club, at 3077 Motor Ave. Named defendants included actor Jack Lemmon, movie producer Richard A. Quine and lawyer Robert A. Eaton, owners; actress Edie Adams, former owner, and Jack Broder [1904-1979] and his wife, Beatrice [Helen (Fabrick) 1918-1985], managers.

The 12 couples and one man who filed the suit asked $15,000 damages each. They demanded “modulation” of music, loudspeakers, tennis and swimming events and asked for more complete parking facilities.

In April, 1964, Jack Broder was president, and Tommy Cook the tennis pro. (L. A. Evening Citizen News, Apr. 8, 1964).

Cheviot Club or Cheviot Hills Club (1972)

In November 1972, the site was the “Cheviot Club” (L. A. Times, Nov. 9, 1972) or “Cheviot Hills Club” (L. A. Times, Nov. 16, 1972).

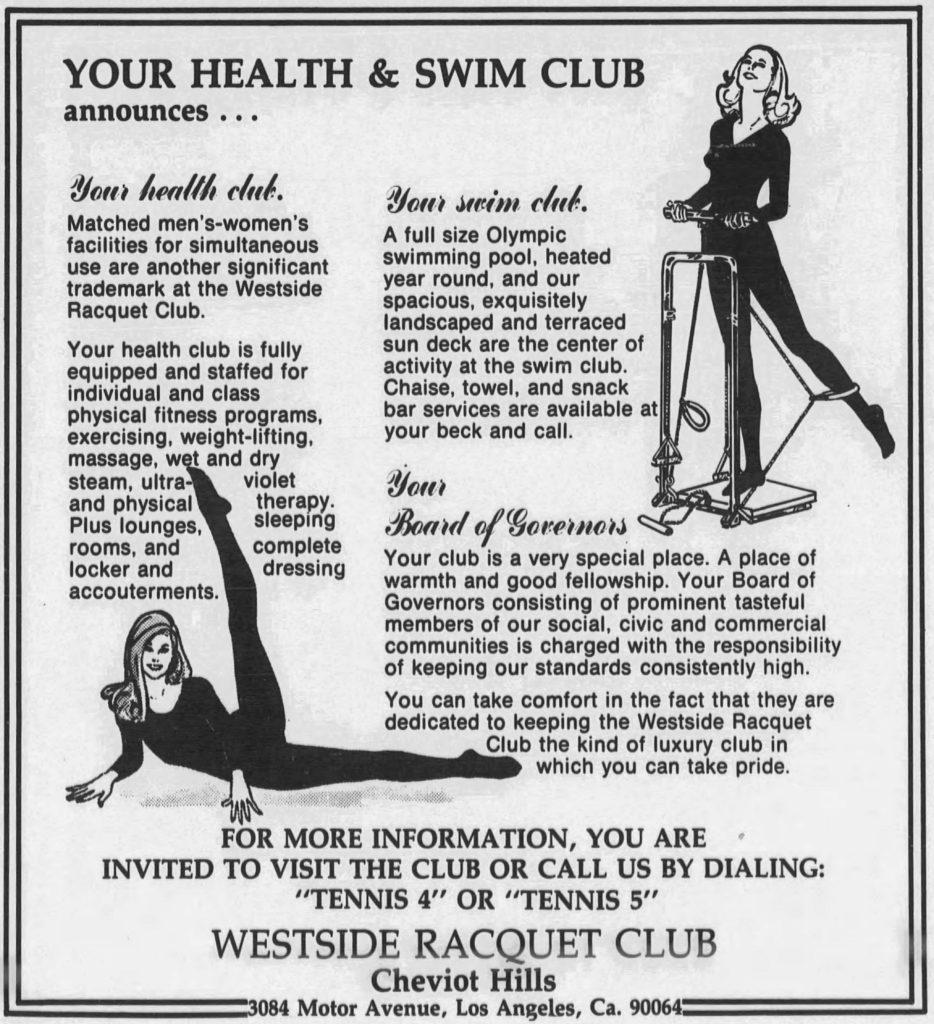

Westside Racquet Club (1973-1985)

In May 1973, the Los Angeles Times reported the club’s celebrity-filled board: “Bill Cosby, Kirk Douglas, Clint Eastwood, Janet Leigh Brandt and Liza Minelli have joined the board of governors of the new Westside Racquet Club.”

In 1985, Knight Development Corp. bought the club and planned improvements, upsetting some neighbors. Knight initially prevailed, with the Los Angeles Time reporting in December 1985, “Racquet Club Scores Win Over Neighbors.” But that was only the beginning of the legal contest with the area homeowners’ association which alleged the club brought traffic, noise, parking, and public urination. The article (excerpted below) covered ownership, membership, and why the club in the residential neighborhood had the right to keep operating as it had.

When Knight Development Corp. bought the Westside Racquet Club last year, the new ownership expected neighbors to welcome plans to refurbish the run-down, 60-year-old facility that once was a retreat for such Hollywood luminaries as Humphrey Bogart and Errol Flynn.

Owned in the past by, among others, Ernie Kovacs and Jack Lemmon, the Cheviot Hills club at 3084 Motor Ave. has fallen on hard times. The roof leaks, the kitchen is outdated and repairs are needed everywhere, according to Gene Axelrod, president of the corporation.

“We thought the people living near the club would welcome us with open arms,” Axelrod said. “We planned to fix up the facility, bring it up to modern standards and develop it into a first-class recreational and social club.

“Surprise! We have not been able to overcome the fears of a small group of homeowners who refuse to believe that we will be good neighbors. They have opposed us at every opportunity, despite our best efforts to reach an accommodation with them. We still intend to be a good neighbor.”

The company will have a chance to stand by its promises. After winning approval to proceed with construction, refurbishing is due to begin Monday.

Opponents of Axelrod’s plans would like to be able to accept his assurances, said Jerold Steiner, a board member of the Cheviot Hills Homeowners Assn., which has led the fight against the club.

“The problem is,” Steiner said, “that we want more than assurances. We want controls to be placed on the operation of the club to guarantee that there will not be excessive noise, parking in the neighborhood and a general intensification of activities at the facility.

“In the past, neighbors have had to live with all of those problems–noisy parties until all hours of the night, parking in the neighborhood, urinating on people’s lawns when they leave the club. While we recognize the club’s right to exist, we will accept nothing less than tight controls to preserve the tranquility of the neighborhood.”

Steiner and Axelrod made their comments after a Los Angeles Board of Zoning Administration decision Tuesday that allowed Knight Development, a Hawaii-based developer, to refurbish the building without a public hearing.

Axelrod said he plans to rename the facility the Beverly Hills Country Club, charge members a fee of $5,000 or $8,000 and provide them with “first-class” dining, health, exercise and relaxation facilities. He also plans to provide such business amenities as offices and limousine service.

The Cheviot Hills Homeowners Assn. and two other complainants had argued that a public hearing was required under city law because the developer was planning to change the operating conditions of the club established by the zoning administrator 30 years ago when the clubhouse was expanded to its existing size.

The homeowners maintained that the only approved uses for the existing facility are tennis, swimming, a limited number of gym activities, casual dining and drinking.

Lengthy Arguments

After listening to nearly six hours of arguments from both sides, the board ruled 3 to 1 that a public hearing was not required and that Chief Zoning Administrator Frank B. Eberhard was correct in approving the refurbishment because there was no increase planned in the size of the 34,000-square foot structure.

Board members and Eberhard expressed sympathy for the homeowners and said that they will closely monitor both Knight Development’s building plans and future club operations to ensure that club activities do not disrupt the neighborhood.

“We heard the words of assurance from Eberhard,” Steiner said. “We simply do not think they mean anything.”

The association will meet Monday to consider several options, including a possible appeal for a City Council hearing, a lawsuit and meetings with Axelrod to reach an agreement on operations that satisfies the club’s neighbors, Steiner said.

Steiner said most of the approximately 1,800 homeowners in the area support the association’s position on the club. This does not include Country Club Estates, a group of 450 homeowners who have reached an agreement with Knight Development Corp. to submit disputes to arbitration.

Eberhard said in an interview after the hearing that he and board members were frustrated by the case and the action taken because they sympathize with neighborhood fears about future operation of the facility.

‘Cannot Act on Fear‘

“But as a matter of law,” Eberhard said, “we cannot act on fear or speculation. We can only deal with violations when they occur – and we will act if there are violations.”

He said that such a facility could not be built in a residential area today and that had he been the zoning administrator in 1955 he would have imposed tighter restrictions on the club’s activities.

“But that is knowing what I know now,” Eberhard said. “The rights of the club were established in 1926, when it opened, and in 1955 when it was expanded. You do not lose those rights unless you violate the law and become a public nuisance.”

Beverly Hills Country Club (1986-2017)

‘By the start of 1986, the Cheviot Hills Homeowners Association had sued the City of Los Angeles challenging its approval of the club’s renovation. “Carlyle W. Hall, Jr., attorney for the association, said the association wants strict controls on the club’s hours of operation, parking and noise.” The news story said the club’s board of directors included “Armand Hammer and Fred Hartley, actors Tom Selleck and Jim Nabors (1930-2017) and educators Charles E. Young and Norman Cousins.”‘

Bloomberg listed the following on the Beverly Hills Country Club’s board: Buzz Aldrin, Gene Axelrod, Bjorn Borg, Yvonne Burke, Chris Carter, Jimmy Connors, Barbara Eden, Robert Finkelstein, Lawrence Gordon, Dale Gribow, Merv Griffin (1925-2007), George Hamilton, Peter Kelly III, Sherry Lansing, Chapin Hunt, Frank Jobe (1925-2014), Spencer Johnson, Rafer Johnson (1934-2020), Phil McGraw, Leslie Moonves, Jimmy Murphy, Jim Nabors, Matthew Perry, Wolfgang Puck, George Schlatter, Tom Selleck, Nancy Sinatra, Tina Sinatra, John Tunney, Arthur Ulene, Andrea Van de Kamp, Gary Wilson, and Harvey Zarem.

Bloomberg also listed Beverly Hills Country Club’s “key executives” as: Greg Walker, Tennis Professional; Sara Berger, Catering Director; Paulo Hexsel, Executive Director of Tennis; and Trevor Sands, Director of Tennis.

On May 11, 2015, the Times reported the club’s sale, including:

Singerman Real Estate, a Chicago investment firm, and Meriwether Cos., a Boulder, Colo., hospitality and resort development company, bought the four-acre property near the Santa Monica Freeway south of Century City. Terms of the sale were not disclosed, but the new owners promised to spend $10 million on renovations to the dated complex. The seller was L.A. Partners, headed by Gene Axelrod, which had owned the property since 1985. “The Beverly Hills Country Club has served the local community for almost 90 years,” said Meriwether Cos. Managing Partner Graham Culp. ” And we are excited to help ensure it remains a place for Southern California families to gather and socialize for the next 90 years.” Singerman Real Estate is the majority owner of the club. Meriwether Cos. and Los Angeles real estate investor Kris Thabit are responsible for day-to-day operations. The club has about 1,500 members. Monthly dues range from $175 to more than $350. Dues will not rise until renovations are completed, the owners said.

Griffin Club Los Angeles (2017-present)

In August 2017, the Hollywood Reporter covered the club’s reopening as the Griffin Club. (Of course, it repeated the Elmer Griffin origin story.) Interviewed for the story, Graham Culp said:

“Our hope is that it will become a place for entertainment industry types who could meet here on neutral ground and hold meetings and events. And for our high-profile members, we want to make it a safe environment.” Ty Burrell, Josh Gad and writer Chris McKenna (whose credits include Spider-Man: Homecoming) are some of the members who enjoy the family-oriented, paparazzi-free zone.

The Hollywood Reporter outlined changes in the operation:

The main clubhouse features a new staircase and bay windows; works by local artists adorn the walls; Jeff Torin, formerly of Petit Ermitage, has been brought in for the dining (casual California fare, including standout short rib mole tacos). The refashioned upstairs bar is complemented by a poolside bar (take that, Soho House). Fitness areas were upgraded with state-of- the-art cardio machines, a newly outfitted weight room and a Pilates studio. Locker rooms were given a fresh finish with retro-tiled showers. Woodland Hills-based design firm Creative Resource Associates worked with blues, neutrals and warm grays to modernize the interiors.

Over the past two years, more than half of the club’s old guard opted out of the new vision, which includes a stricter membership policy and a revamped fee structure. But director of membership John Myers says that defectors already have been replaced, and there are currently about 1,500 family and non-family memberships. One-third of members live locally in suburb-like Cheviot Hills (once home to Lucille Ball, the neighborhood also has bragging rights to the Modern Family house), where the median residential property value is $1.8 million — up 2.9 percent over 2016, according to Zillow. The one-time entry fee for Griffin Club ranges from $4,000 to $10,000 — well below the six figures at most L.A. country clubs (but Griffin doesn’t offer golf). Still, the club shares the selectivity of its pricier peers: For the foreseeable future, it will be expanding by invitation only, with prospective members required to have at least two current member referrals.

In April 2018, ACORE Capital provided a five-year, $46 million-dollar, loan (replacing a $30 million dollar loan) allowing for future work on the property, including an expansion of the club’s kitchen services. (The Real Deal, April 23, 2018.)

Hervé Lévy was the club’s general manager and chief operating officer from 2015-2021.