CULVER CITY

A Calendar of Events

In which is included, also, the story of Palms and Playa Del Rey together with Rancho La Ballona

and Rancho Rincón de los Bueyes

By Robinson, W. W. (1939)

1769

The title to all land in California becomes vested in the King of Spain.

The Culver City area was off the main highway of travel during the period of first white occupation of California which began in 1769.

It lay in the valley formed by La Ballona Creek flowing toward Playa del Rey, a year-round river draining the whole of the west Los Angeles region and fed directly from the chain of cienegas and lakes that stretched from the Hollywood mountains to the Baldwin Hills. This valley was a place of rich silt, the higher ground being the present Culver City, the lower ground being the extensive marshes that stretch far back of the lagoon at La Ballona’s mouth. Sycamores, willows and tules lined the river.

On old maps the cliffs of Ballona’s easterly boundary are labeled “Guacho,” sometimes “Huacho,” an Indian term meaning high place, according to Cristobal Machado of Culver City, whose memory of La Ballona Valley goes back to Indian days. It was against these cliffs that the Indians built their brush-and-mud huts. From them the brown-skinned men went forth to gather clams and shell fish at the beach beyond the lagoon, to hunt small game in the marshes and to find edible berries, seeds and insects in the river growth and on hillside shrubs.

1781

Los Angeles is founded and, while the pueblo is still young, its citizens discover that the Culver City valley is good pasture ground for cattle.

Within the decade after the eleven families from Sonora and Sinaloa started building Los Angeles’ first houses, the names of Machado, Higuera, Talamantes and Lopez were established in the community.

Members of these families were to become the first white settlers along Ballona Creek, the first white occupants of the valley land that stretches from Culver City to the sea.

One of the soldier-guard who came from Sonora to Los Angeles in 1781 was 25-year-old Jose’ Manuel Machado. He brought with him a 17-year-old wife, Maria. It was this Machado whose sons Augustin and Ygnacio were to settle Rancho La Ballona.

A few years after the founding of the Pueblo, Felipe Talamantes and his brother Tomas became Los Angeles citizens. Later they shared with the young Machado men in their ranch venture.

The alcalde of the pueblo in the year 1800 was Joaquin Higuera. His son, Bernardo, was to settle the land that adjoined the Rancho La Ballona on the northeast — Rancho Rincón de los Bueyes.

Meanwhile the people of the pueblo, with vague ideas about the boundaries of their own four square leagues of land, needed more good pasturage for their cattle. The Rincón and the Ballona, lying to the southwest, could qualify and in addition were so far from San Gabriel and San Fernando as to be unclaimed by the Missions.

At a very early period, then, cattle owners from the pueblo were visiting the Culver City valley.

1819 – 1821

White men settle the Ballona and the Rincón: site of Culver City.

— The Ballona —

“We occupied, with our grazing stock, houses and other interests, the place called ‘Pass of the Carretas,’ but more generally known by the name of the Ballona.”

This was the statement of Augustin and Ygnacio Machado and Felipe and Tomas Talamantes. They made this statement on September 19, 1839, in a petition for confirmation of their title. It had been “about the space of eighteen or nineteen years,” they said, “since they had moved in, under a permit from the military commander José de la Guerra y Noriega. Another source, the historian Bancroft, indicates the date was probably 1819, for in that year the Church was protesting, without avail, a cattle-grazing permit given by Noriega to these four citizens of Los Angeles. The permit itself, unfortunately, is not among the United States Land Commission records, though it is referred to.

Augustin and Ygnacio Machado were young men in 1819 — so young they would have received no ranch favors from the government, according to family tradition, without taking the older Talamantes brothers into partnership.

The road through the “Pass of the Carretas” — paso de las Carretas it appears on first maps — was the ancestor of Washington Boulevard. To appreciate that this old sandy road was actually a pass between hills, the visitor of today need only stand on California Country Club or Pacific Military Academy property, and look toward the nearest point of the Baldwin Hills.

— The Rincón —

The Rincón was settled in the last month of 1821, under another concession from Noriega. A petition was delivered to him, written and dated on December 5, 1821. It read:

To the Snr. CapN

Bernardo Higuera and Cornelio Lopez, citizens of the Pueblo de Nuestra Señora la Reina de Los Angeles, and under the command of our honor, with the greatest respect and submission before your Excellency, appear and say that, possessing at the present time a number of cattle and not having any place so as properly to be able to keep them with a grazing ground of sufficient extent . . . . Therefore ask and beseech your extreme clemency to be pleased to grant to them the tract within this vicinity called Corral Viejo del Rincón so as that they may be able to place a corral for herding the said cattle unless it does some injury to the neighboring residents — a favor they expect from your extreme goodness and for which they will recognize themselves very grateful. May God preserve you many years.”

This petition was signed at Los Angeles by Bernardo Higuera and Cornelio Lopez.

Two days later Noriega made an entry on the margin of the petition:

“Pueblo de Nuestra Señora de Los Angeles. Dec. 7, 1821. It is granted if no prejudice result to the community. (Signed) Noriega.”

— — — — — —

The origin of the word “Ballona” is in doubt. It does not appear on first maps. There is no basis in the old records or in local tradition for the common explanation of its being a corruption of “Ballena,” meaning whale. “More likely,” says Cristobal Machado, “it comes, somehow, from the word ‘bay’.” Certainly the bay was the big feature of Rancho La Ballona, for at flood time waters of the lagoon and the marshes backed up nearly to the present Culver City.

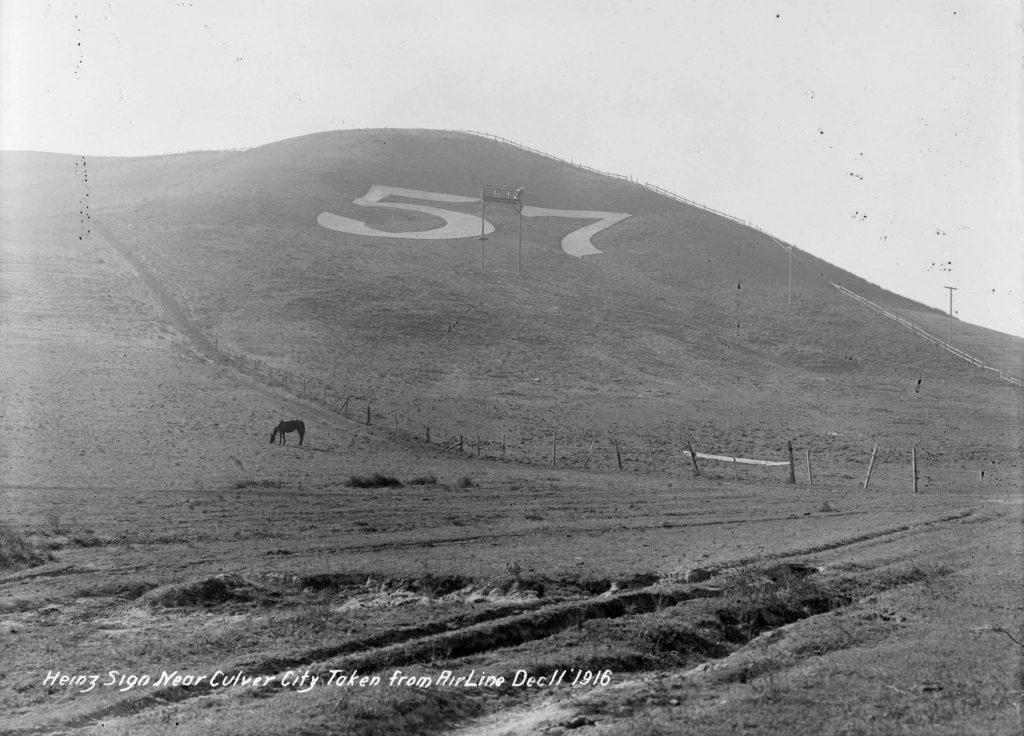

The origin of “Rincón de los Bueyes” — corner for cattle — is simpler. The “Rincón,” meaning corner, was the natural corral created by a ravine in the Baldwin Hills which lies just southwesterly of the large advertising sign of “57.” From that “corner, with its rising knolls — attractive to grazing cattle — the name was applied to the rancho.

1822

Spanish control of California ends.

1839

The owners of La Ballona get a grant from the Governor, and two ranchos go in for cattle, corn and wine.

During the twenty years that. La Ballona had been occupied by members of the Machado and Talamantes families, or their representatives, they had stocked the ranch with “large cattle and horses and small cattle” and had improved it “with vineyards and houses and sowing grounds.”

Augustin Machado had married Ramona, the daughter of Francisco Sepulveda, a neighbor rancher. Augustin had built an adobe home near Ballona Creek, just northeast of the present Overland Avenue. One home, probably not his first, had been washed away by floods. The next he placed on higher ground, in the same general location, but facing what is now Jefferson Boulevard. The site of the last ranch house is today a Japanese beetfield.

Ygnacio Machado had married Estefana Palomares and had built a home farther up the stream.

The work of the ranch was done by the local Indians, one group of whom had their huts among the sycamores not far from Augustin’s home, another group having their village against the cliffs beneath the present-day Loyola University.

Both brothers were widely known. They were respected as honorable men, generous and just.

On November 27, 1839, Governor Alvarado confirmed the Machado-Talamantes title by giving the four owners a grant. This followed the request made in September when they expressed a wish “to secure in the best possible mode the maintenance of our increased families.” None of the four petitioners could write.

About a month later they were given formal, or “judicial,” possession. This was done in the presence of the neighbors: Policarpio Higuera (of the Rancho Rincón de los Bueyes), who, incidentally, was one of the official cordbearers at the ceremony; Antonio Ygnacio Avila (of Rancho Sausal Redondo); Francisco Sepulveda (of Rancho San Vicente); and Maximo Alanis (of Rancho San José de Buenos Ayres).

In 1833 or 1834 Ygnacio Machado had moved into the Canada del Centinela, west of Inglewood’s Centinela Springs. This left Augustin in full charge of La Ballona, for the Talamantes brothers lived on the Rincón de los Bueyes.

It was during this period and in the years following that Augustin Machado’s white wine, produced on La Ballona, attained fame throughout California for its excellence. It ranked with the red wine for which San Gabriel was famous. Augustin’s blond vintage cost ten dollars at the ranch for an eighteen-gallon barrel, and the agents sold it in the north for twenty-five dollars.

To get the necessities and luxuries that came only from New England and the Orient, it was Augustin’s custom to go to San Pedro where the foreign traders anchored. He would send an ox-drawn carreta over the old road through the hills and over the site of Inglewood. He followed on horseback. One time, after selecting goods aboard ship, he was asked by the supercargo’s new assistant to give a note or a guaranty — an unheard of procedure in California. For a moment Augustin was speechless. Then he pulled a hair from his beard, handed it to the youth and said: “Here, deliver this to Señor Aguirre (the ship owner). Tell him it is a hair from the beard of Augustin Machado.”

Meanwhile there had been changes on the Rincón , where the Higueras went in for cattle, horses, corn, pumpkins and beans, as well as vineyards.

It (the Rincón) was occupied when I first knew it,” testified Januario Avila many years later, “by Bernardo Higuera jointly with Cornelio Lopez. Cornelio Lopez abandoned it and it was then occupied by Bernardo Higuera during his lifetime and after his death by his children. It is now (in 1852) occupied by Francisco Higuera, one of the sons of the late Bernardo. Bernardo built the two houses on the land about the year 1822 or 1823 and he lived on the land and the family have lived there ever since . . . .

Bernardo “verbally ceded” his interest to his brother Policarpio in 1834, according to the old records. Policarpio, together with another brother, Mariano, Bernardo’s son Francisco, and Pedro Mendez claimed title in 1848 by “denouncement,” saying that the deceased Bernardo had abandoned the ranch. The 1836 census showed Bernardo and his wife, Maria Rosalia Palomares, living in Los Angeles.

“I lived in the family of the late Policarpio,” said Francisco Botiller. “I also knew a man by the name of Pedro Mendez who lived on the rancho with Policarpio . . . I left the family quite young, but lived in their vicinity afterwards. I know when Mendez came there but cannot tell how long ago. I know when Mendez left, but cannot fix the time. It was after Policarpio’s death, which happened soon after Micheltorena came to Los Angeles. After Policarpio’s death, Mendez sold the small house he had on the place to Policarpio’s widow for three or four tame cows, I believe, which were then worth about six dollars each. I was not present at the bargain, but I was told of it by both the widow and Mendez. I saw two of the cows in the possession of Mendez. Mendez then took away everything he had from the place and never returned” . . . .

In 1843 Francisco Higuera was having a dispute with his fiery neighbor, Vicente Sanchez, who allowed hogs to pasture on the Rincón and who, Francisco feared, was claiming his land.

Francisco’s adobe stood on the present site of the Casserini ranch house. It was close enough to La Ballona Creek for Francisco’s nine children to swim in the clear waters of the stream with its fine sandy bottom. Not far from the adobe was the “little orchard,” with its olive, apple, pear and pomegranate trees.

1848

California becomes part of the United States by the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo.

Francisco Higuera, it is told, fought in the Battle of San Pasqual — one of the sad preliminaries to the taking of California by the United States. He wounded and unhorsed Captain Gillespie and took Gillespie’s saddle. “It was that fine saddle,” Ynezita Higuera — Francisco’s granddaughter — tells us, “that saved Gillespie’s life.”

1850

California comes into the Union as a state.

The United States Board of Land Commissioners receives petitions from Machados, Talamantes and Higueras.

In October of 1852 the families owning La Ballona and El Rincon filed their claims with the Commission which had been established the year before to settle all land claims.

The Machados and Talamantes had smooth sailing. The Board gave them its approval on February 14, 1854, and the United States District Court upheld the decision on appeal.

The Higueras were not so lucky. They were turned down at first. Not until the end of 1869 was their claim upheld in the District Court.

When the United States finally issued its patent covering Rancho La Ballona, on December 8, 1873, it confirmed the title to nearly 14,000 acres. The patentees were the original four claimants. The patent covering Rancho Rincon de los Bueyes, issued on August 27, 1872, confirmed title to 3100 acres, the patentees being Francisco and Secundino Higuera.

1854

Tomas Talamantes borrows money and signs a mortgage: first steps toward the break-up of Rancho La Ballona.

Tomas Talamantes, one of the four owners of La Ballona, needed money. Two Americans, Benjamin D. Wilson — Don Benito he was called — and William T. B. Sanford, obliged him with a loan of $1500.

The note was dated June 14, 1854. It was to run for six months, with interest at five per cent per month until paid. The mortgage securing it covered Tomas’ undivided fourth part of the whole rancho.

Tomas was like other Spanish Californians who borrowed money from Yankee invaders. He couldn’t keep up the interest. Before the end of the year the lenders had gone to court and recovered a judgment against him of $2353.26, with interest at five per cent per month from September 25, 1854, and an additional sum of $239.81. On December 6, 1855, a writ of execution was issued, and at that time the interest was $1690.28.

In the forenoon of December 31, 1855, a public auction sale by Sheriff Alexander was held in front of the court house in Los Angeles. Notice had been given in English and Spanish. The highest bidder was Benjamin D. Wilson whose offer was $2000.00.

On January 2, 1857, the Sheriff gave Wilson a deed, and Wilson became a fourth owner of a great rancho.

The death, the year before, of Felipe Talamantes — the oldest of the four original owners — helped further to complicate ranch ownership, for he left twenty-five heirs and devisees.

1861

Echoes of the Civil War are heard in La Ballona.

1865

Augustin Machado dies.

The best known of the original four owners of La Ballona died on May 17, 1865.

Augustin’s wife was a Sepulveda, and Judge Sepulveda heard probate cases in Los Angeles County. So, the administration of the estate was transferred to San Bernardino County.

Two years later Ygnacio Machado deeded most of his interest in the ranch to relatives.

Partition of the Ballona was now unavoidable.

At the outset of the Civil War southern California’s sympathies were so strongly southern that the national government kept it under close watch — with one force of troops established at Drum Barracks, near Wilmington, and another at Camp Latham on the slope of the Baldwin Hills near Ballona Creek.

1868

La Ballona is partitioned.

In 1859 Benjamin D. Wilson, the first American to be an owner of Rancho La Ballona, had sold his undivided fourth interest for $5500.00. The purchasers were John Sanford, James T. Young and John D. Young, who, in 1863, petitioned the District Court (Case 965) for a partition of the great ranch.

It took five years to obtain a partition decree.

In the partition of May 14, 1868, those who received allotments were:

John D. Young

George A. Sanford

Elenda Young

Addison Rose

Willis G. Prather

Macedonio Aguilar

Benina Talamantes

Estate of Augustin Machado

Gregoria Talamantes

Tomasa Talamantes

Pedro Talamantes

Jacinto Talamantes

Jesus Talamantes

Lauriano Talamantes

Manuel Valenzuela

Francisco Machado

Dolores Machado

Andres Machado

José Machado

Antonio Machado

Rafael Machado

Cristoval Machado

Ygnacio Machado

Each person got, in the partition, three kinds of land: “pasture” lands; “irrigable” lands; and “lands in Bay.”

Each person got beach frontage. To make this possible, it was necessary, in some instances, to describe and plat narrow strips of land connecting interior allotments with the sea. Some strips were two and a half miles long, though no wider than a city lot.

The largest allotments were to the “Estate of Augustin Machado.” By a later partition, in 1875 these were redivided among the heirs of Augustin.

Up on the pasture lands allotted to Macedonio Aguilar was to arise most of Palms and later Culver City.

1871

William Tell, a squatter, files a claim to part of La Ballona and establishes a seaside resort.

Will Tell sometimes called William Tell, who once kept a paint shop in the Temple Block, Los Angeles, filed a preemption claim to one hundred and fifty acres in the vicinity of Del Rey Lagoon at the mouth of Ballona Creek.

On the edge of the lagoon he built a home for himself and Mrs. Tell. He called it Will Tell’s Sea Shore Retreat, also Tell’s Lookout. The lagoon became the William Tell Lake. The Tells got eight or ten boats, together with a supply of fishing tackle, guns and Don Mateo Keller’s brandies. They ran the place for the benefit of picnic, boating and duck-hunting parties.

The widow of Augustin Machado started an action to evict the Tells in 1874, but it was allowed to lapse, and the Tells moved on to Santa Monica. An Irishman named Michael Duffy “took over” for a while, with his Hunter’s Cottage, from which he advertised that he was prepared to “furnish sportsmen with board and lodging for man and beast.” High tides came along, finally, to destroy the resort.

The whole marsh area of La Ballona long remained a favorite place for duck hunters. Among the gun clubs of the area were the Centinela, the Del Rey and the Recreation.

1886

Subdividers come to La Ballona and create “The Palms.”

Three subdividers, Joseph Curtis [1839-1920], E. H. [Edward Healey] Sweetser [1844-1916] and C. J. [sic] [Cornelius Gooding] Harrison [1829-1904], looked upon the good earth and the good location of Rancho La Ballona. They may have foreseen the boom that was about to hit southern California. These men laid out and subdivided a triangular tract, the map of which became official by its recording on December 24, 1886. They called it “The Palms.”

The land within “The Palms” was bounded by Ballona Road, now Washington Boulevard, by First Street, now Overland Avenue, and by Manning Avenue.

The subdivision was carved out of a five-hundred-acre tract which was a part of Macedonio Aguilar’s allotment in the partition of the Rancho. Curtis, Sweetser and Harrison paid $40, 000 for the five hundred acres. (Rita Botiller de Aguilar, widow of Macedonio, had succeeded to her husband’s title in 1871. In 1883 she made a gift deed of the land to J. F. Figueroa, her grandson. Figueroa, six months later, sold the property to E. H. Owen and Albert Rimpau for $17,500.00. He reserved for his own use seventeen acres, at the present northeast corner of Washington and Overland. In 1886 the new owners conveyed to W. A. Clinton, H. Clay Graham, J. M. Taylor and C. J. Fox, the sales price, still rising, being $37,500.00. A few months later the subdividers bought them out.)

Before this invasion of subdividers there were only two roads through the region — the one that is Washington and the other that forked off toward San Vicente (Santa Monica). For travelers there was the Half Way House, directly west of Francisco Higuera’s adobe and half way between Los Angeles and Santa Monica — on the site of the Beacon Laundry near the Helms Bakeries. This House was well known for its wines and pickled olives.

1887

A great harbor — Port Ballona — is planned, as the boom hits the two ranchos.

The old ranchos of the Machado, Talamantes and Higuera families felt new stirrings of life when the real estate boom of the Eighties began to transform the landscape of southern California.

In “The Palms” the subdividers resubdivided, putting in more streets and more lots. In the Rincón de los Bueyes an old survey was brought out and recorded by José De Arnaz, who had bought a large portion northwest of Washington Boulevard from Secundino Higuera (in 1849) and Francisco Higuera (in 1867).

The greatest activity was at the mouth of La Ballona Creek, now Playa Del Rey, where a harbor — magnificently outlined on paper — was being constructed out of the old lagoon that had been the haunt of duck-hunters and picnickers since Indian days. The harbor was the brain child of Moye L. Wicks. He had been urging it since 1885, ever since Los Angeles began hunting for a tidewater terminal for the Santa Fe Railroad. The Ballona Harbor and Improvement Company, under the guidance of M. L. Wicks, H. W. Mills, R. F. Lotspeich, Frank Sabichi and others, was organized in 1886, with a capital stock of $300,000.00. Engineer Hugh Crable was employed to lay out a harbor to “float the fleets of the world.”

By dredging, the Company hoped to create a 200-foot channel and an inner harbor two miles long, 300 to 600 feet wide and six to twenty feet deep. A right of way was granted the California Central Railway Company (Santa Fe) and a railroad was laid, connecting Los Angeles with the proposed harbor. A small steam dredger began work and two piers were constructed.

Meanwhile, on the cliffs above, the “Town of Port Ballona” was laid out. The building of homes began and the sound of carpenters’ hammers filled the air.

On August 21, 1887, the railroad was finished and the first train brought an excursion load of three hundred prominent Angelenos to Port Ballona. They listened to optimistic speeches and happy predictions.

The boom burst in 1888, the funds of the Ballona Harbor and Improvement Company became exhausted, the sands and the tides continued their opposition — and the dream of Port Ballona remained a dream.

1902

La Ballona’s beach gets a new name Playa Del Rey, and a second lease on life.

Port Ballona, forgotten by all but antiquarians, was refurbished in 1902, given the euphonious name of Playa Del Rey and placed on the real estate market once more. Within Playa Del Rey’s boundaries was included also the beach and land around the lagoon, all nicely subdivided and adorned with a long boardwalk.

This was in the beginning of the period of beach-town expansion in southern California, with the electric railroads behind the movement.

The subdivider was The Beach Land Company, Henry P. Barbour, president. Associated with Barbour were F. H. Rindge, M. H. Sherman, E. P. Clark, E. T. Earl, R. C. Gillis, Arthur Fleming, A. I. Smith and P. M. Green. This Company had acquired from Louis and Joseph Mesmer nearly all of the town of Port Ballona and adjoining property. It gave a sixty-foot right of way to The Los Angeles-Hermosa Beach & Redondo Railway Company, succeeded by Los Angeles Pacific Company, which, in 1911, was to consolidate with the Pacific Electric Railway Company.

A new building period began. A pavilion costing $100,000.00 was built. An eighteen-mile speedway for automobile racing was constructed. The Hotel Del Rey, with fifty guest rooms, arose at a cost of $200,000.00. The lagoon blossomed out with boathouse and grandstands. An inclined railway with two cars — “Alphonse” and “Gaston” — carried passengers up to an observation platform on the palisades above.

Playa Del Rey was on all the excursion routes, and when the electric railroad established its famous “Balloon Trip” for the tourists, Playa Del Rey was a favorite stop. A fish dinner was served in the pavilion. The tourists were given time to look at the cliffs, the beach, and the lagoon with its “longest bridge span of reinforced concrete in the world,” before being carried on to gather moonstones on Moonstone Beach near Redondo. Many bought lots and built attractive seaside homes along the beach in front of Rancho La Ballona.

For many years afterward Playa Del Rey was a popular seaside resort. On holidays it was crowded with auto-racing and boat-racing fans. But when the pavilion and hotel burned down, when the grandstand was removed and when sand filled the boat course, Playa Del Rey fell into decay.

Not until the middle twenties did subdividers come back and this time they devoted themselves successfully to the mesa and cliffs above.

Out of their efforts came “Palisades Del Rey” and “Surfridge” — residence areas still in the building — whose substantial homes command today a high view of the sea. At the foot of the cliffs is the attractive Westport Beach Club.

1912

Subdividers pick the high land of La Ballona and the outlines of Culver City appear.

On July 16, 1912, the Washington Boulevard Improvement Company subdivided the remainder of Macedonia Aguilar’s pasture-land.

This was the 150-acre piece of land adjoining “The Palms” on the southeast that J. F. Figueroa sold to Victor Ponet in 1886 for $7500.00. It extended from Washington Boulevard to Ballona Creek and included much of the present Culver City. On the southwest it extended half a block beyond Jackson Avenue. It was officially named “Tract No. 1775” but popularly called Washington Park. It carried the lay-out of streets, blocks and lots that has continued to date. Streets were given the names of presidents and other prominent figures in American history. Putnam Avenue was later to be changed to Culver Boulevard.

The Washington Boulevard Improvement Company did not buy this land directly from Victor Ponet. Ponet deeded to Alice Dana in 1906. Later in the same year Dana conveyed to M. J. Nolan, J. W. Vaughn and A. H. Busch, the three gentlemen whose title was acquired in 1912 by the subdividing corporation.

C. Cereghino guided this corporation. He and his associates, from San Francisco and Oakland, on a trip through La Ballona, had picked this high land as the best for investment and subdivision. Cereghino is still satisfied with his selection for he lives today surrounded by orchard and garden on the acreage he reserved for himself on Madison Avenue, Culver City, within Tract No. 1775.

1913

Culver City is born.

The announcement that a city, partly residential, partly business, was about to be born, climaxed a banquet held at the California Club in Los Angeles on July 25, 1913. At the tables sat the directors and stockholders of the newly formed Culver Investment Company, and a few of their friends. On this occasion the unborn town was christened “Culver City,” honoring its enthusiastic father, Harry H. Culver.

Culver, whose birthplace was Milford, Nebraska, and who had been educated in Nebraska, had come to Los Angeles in 1910. He had gone into the real estate business, turning his attention to the land lying midway between Los Angeles and Venice.

Into the quiescent barley-field region of Palms, Washington Park and the surrounding countryside, where land was not “moving” fast enough to suit him, Harry Culver introduced new ideas in financing, advertising, and selling. He conceived the notion of a city on the highway between Los Angeles and the sea. He sought the help of the Pacific Electric Railway Company and of several land owners. He organized the Culver Investment Company, bought a group of blocks in Palms and some acreage adjoining: property lying northwest of Washington Boulevard. He secured the aid of P. H. Albright, civil engineer, and went to work on a subdivision that would form the heart of the city to be.

Bulletins issued from the Los Angeles offices of Harry H. Culver & Co., following the banquet at the California Club, throw sidelights on what was happening in the newly acquired barley fields and in lands in the area: —

July 27th — “Acreage values between Los Angeles and Venice are certain to experience a sharp advance.”

August 17th — “Watch Los Angeles-Venice acreage go to $5000.00 . . . Culver City big improvement — work will begin . . . We have a few very attractive snaps.”

August 31st — “The dirt is now flying fast. Acreage values increasing with wonderful rapidity.”

September 7th — “Intense activity. There are now thirty subdivisions. Venice is growing toward Los Angeles. Los Angeles is growing toward Venice.”

On September 11, 1913, the Culver Investment Company’s subdivision (Tract No. 2444) became official by being recorded in the County Recorder’s office.

In later years, a local newspaper, in reminiscent mood, was able to say that “the fields became transformed and in their stead homes began to sprout and groups of industries and marts were springing up where barley leaves waved gently in the breeze.”

Culver City, born in a whirl of real estate activity, was to become the community, “partly residential, partly business,” that its founder planned.

The first building in the new subdivision was Harry Culver’s real estate office. Before a year had gone by, there was a grocery store, a plumbing and hardware shop, a candy store a newspaper (The Culver City Call), two churches, seven miles of sidewalks and curbs, a lighting system, a railroad station, an express company, a macaroni factory, many homes and 150 real estate salesmen.

1915

La Ballona Creek carries canoes in a movie scene and the Culver City motion picture industry is born.

Thomas H. Ince, producing pictures at Inceville, on the coast above Santa Monica, needed a stream of water that could float three canoes full of Indians.

The Los Angeles River at the time was incapable of such an act and the Colorado River was too far away.

La Ballona Creek came to the rescue. Canoes filled with painted savages floated on its surface. The scene was shot under the bridge at Casserini Ranch, not very far from the site of Francisco Higuera’s homestead. One of the most interested spectators was Harry H. Culver.

Ince did more than shoot a scene on La Ballona Creek. He bought a piece of La Ballona Rancho. From E. P. Clark he purchased, in September 1915, a small portion of Macedonio Aguilar’s allotment lying on Washington at Sixth Street, just across from the subdivision of “The Palms.”

This Ince “lot” was the beginning of the Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer “lot.”

Ince deeded his land to the New York Motion Picture Corporation on June 6, 1917. (For a while Keystone and Biograph pictures were produced in the plant, as well as those of the Triangle Studio-Griffith, Ince, Sennett.) Two years later Goldwyn Pictures Corporation succeeded to the title to this and adjoining property. The new owner changed its name to Goldwyn Producing Corporation and later, on May 24, 1924, to Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer Corporation — the “M. G. M.” whose name and pictures are famous throughout the world.

The Ince studio was not the first movie studio in this area, for, according to David Worsfold, historian of Palms, the Kalem Motion Picture Company had established itself in Palms during February of 1915.

1917

Culver City becomes a city in fact – and celebrates.

An all-day carnival was held in the streets of Culver City on September 15, 1917.

The occasion? A week before, the townspeople had gone to the polls in the drug store, at 7011 Main Street, and had voted “yes” on incorporation.

There was a parade in the morning, baseball, side-shows, booths presided over by pretty girls, fireworks in the evening, a grand ball in the club house, vaudeville and a dancing contest for the Peggy Hamilton cup.

Culver City’s incorporation was completed on September 20, 1917, when the board of supervisors filed its declaration with the secretary of state. The boundaries included Culver’s Subdivision (Tract No. 2444), Washington Park (Tract No. 1775) and a portion of “The Palms” that had not been annexed to Los Angeles.

Carnivals were commonplace events in Culver City’s first years. “What seems to attract people,” Harry Culver said later, “is something moving. If an object stands still, people will not pay much attention to it.” Accordingly, under the Culver tutelage, the City developed many novelty stunts to draw southern California’s attention. A few of these were: a Marathon race between Los Angeles and Culver City; a baby contest with a building lot to the winner; a monthly booster parade of decorated cars, headed by a band, to a neighboring town; a picnic of trainmen to Culver City; a polo game in which Fords were substituted for horses; a giant searchlight playing nightly from the top of the Culver City Real Estate Office; Junior Vanderbilt Cup races for boys under sixteen who had made their own cars; and a free trip around the world to the one who proposed the best name for the public park.

1935

The Federal Government gets interested in the “Ballona Creek Project,” and new vistas open to Culver City.

In 1931 the Los Angeles County Flood Control District had proposed the permanent improvement of the Ballona Channel and had included it in its county-wide flood control program.

Subsequently, under the direction of Engineer C. H. Howell, a plan for La Ballona’s improvement was submitted to the Federal Government. In 1935 the United States accepted the job and put it under Army engineering direction.

Major Theodore Wyman, Jr. sent his hundreds of workers to straighten and widen the crooked channel that since prehistoric times had been unable to hold the flood waters of rainy seasons that created lagoons and formed vast swamp areas.

They not only straightened, widened and deepened the meandering river, but they put it in a slope-sided, rock-lined strait-jacket. Also, they built three bridges, with the aid of a federal grant of $800,000.00.

The result has been increased flood protection to a wide area and the reclaiming of swamp land. In addition, there has been created an estuary, formed by the flow of ocean tides, extending two miles inland from the channel mouth. This makes an important rowing course. More, the work of the Army has opened up possibilities of great importance to the whole Culver City region such as new beaches, yacht basins, and an industrial awakening to the dormant land lying between Culver City and the sea. The low land of Rancho La Ballona could well take care of textile plants and airplane factories, while a widened estuary would be a recreational center. With the cooperation of land owners affected Culver City can work this out.

Culver City, with its eight thousand and more people, its homes, studios and industrial life, has arisen on the pasture land of the Machados and the Higueras – settlers of the Spanish period. If Augustin Machado could return today, stand on the site of his homestead and look northwest across La Ballona Creek, he would see no expanse of grassy acres dotted with cattle, but immense structures of the M. G. M. studios. Turning his back on this and looking up at the hills that once cast a shadow over his adobe, he would see them bristling with oil derricks. If Bernardo Higuera could revisit his rancho, he would find hill land covered by the charming homes of Monte Mar Vista and Cheviot Hills, by country clubs and military academies, low land covered by industrial Culver City, as well as by the studios of Selznick International and Hal Roach.

W. W. Robinson, 1939

In the Pass of the Carretas — Washington Boulevard — is no longer heard the creaking of ox-drawn carts. Instead is heard the hum of auto traffic carrying thousands of studio workers and such well-known persons as Myrna Loy, Carole Lombard, Norma Shearer, Janet Gaynor, Nelson Eddy, Jeannette MacDonald, Luise Rainer, Clark Gable, Ronald Coleman, Robert Taylor, Eleanor Powell, Robert Montgomery, Joan Crawford, Wallace Beery, William Powell, Spencer Tracy, Greta Garbo, Lionel Barrymore and Freddie Bartholomew. Culver City looks to the future, rather than to its rancho history. It looks to the continuing expansion of its great film industry. Especially does it look toward the sea and to well considered harbor, recreational and industrial development which will further reclaim the marsh land of La Ballona and put new life into an old rancho. With such development, Culver City, midway between Los Angeles and the ocean, can look to an abundant future.

by William Wilcox Robinson (1891-1972)