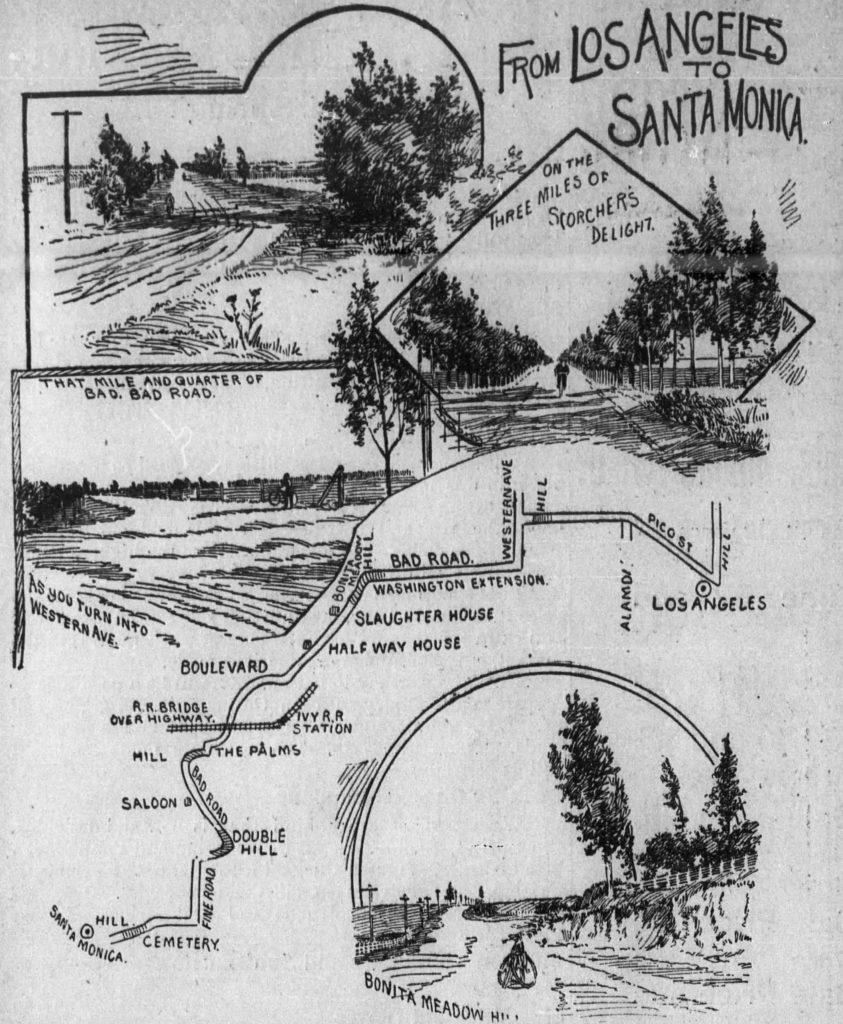

Los Angeles to Santa Monica Bicycle Race

The Fourth of July bicycle race between LA and Santa Monica was held from 1891-1902. The seventeen-mile race did not follow the same route each year. In 1898, it was run in the opposite direction, from Santa Monica to Los Angeles. The starting point eventually moved out of Downtown to avoid traffic. The Santa Monica end of the race was, for a few years, at Third and Utah (today’s Third and Broadway). It always passed through Los Angeles’ early suburb, The Palms.

The Los Angeles Herald‘s July 5, 1895, report is as good as any in capturing the passion for bicycle racing that overtook the area every July 4th. The reporter as breathless in his account as the riders must have been:

All previous records were smashed in the Santa Monica road race yesterday, and cycling men all over the city are enthusiastic over the result as are lovers of the flying wheel in all Southern California.

The crowd surged and peered and called their names as the cracks pushed along to scratch and they cheered them as, at 9 o’clock sharp, they dashed away. Emil Ulbricht got the lead, closely pressed by Herb McCrea, followed in turn by Will Hatton and Will Rodriguez. As they disappeared down Olive street there was a ringing hurrah and the mass of humanity began breaking and flying to catch the 9:10 o’clock special train to be in at the finish.

Officials and assistants scrambled into a waiting coach and the party was driven hastily to the Arcade depot. There was racing and chasing for a brief few minutes and people in carriages, afoot and in the cycle saddle began tumbling into the depot and piling aboard the already heavily loaded seventeen or eighteen coaches, filling the aisles, the baggage car and engine and covering the coal in the tender. The engineer pulled open the throttle and the train raced down the track after the tearing wheelmen.

From the Train

An eager lookout was kept from car windows and all points of vantage for the first glimpse of the riders flying along the road. Little dust clouds barely visible to the naked eye, under the field glass showed a toiling, perspiring rider pumping along merrily toward the Palms. Nearing Palms hill a long stretch was brought plainly into view and the hot pacing racers glimmering like streaks of light though the gauze of dust and sweeping along to their coveted goal.

As the train thundered across the bridge over the road down Palms hill and the scattered field went tearing under it, yells of encouragement broke from the cars and cheers told the struggling racers that they would be warmly greeted on the finish. For some little distance they were kept in view, then the road turned and the train passed the wheelmen, leaving them far out of sight.

At the Finish

Santa Monica was out en masse to see the Los Angeles wheelmen finish the great annual race named after that beautiful summer city. When the crowds from the train rushed through the deserted streets to the point of finish, they found swarms of people crowding toward every point of vantage. The officials took their places, the police lined the crush back of the boundaries and within a very brief space the cry of “Here they come” was heard. But it was a false alarm: only a couple of women bloomers regaled the eyes of the eager crowd, and they themselves were greeted with remarks calculated to worry the most impervious new woman. When they had ridden an exhibition over the course, a lookout announced a rider in view, and with the cheers a dirty, dusty specter careered down the stretch and rolled across the tape with a triumphant smile that emphasized the pride of victory that filled his eyes.

The rider was Louis Lawton, a stranger, a young man from Duarte, who surprised the talent by taking the first place and making his race in the good time of 50:09 ….

Close on their heels came other tired and dusty riders, singly, by twos and in groups. Some of them rode painfully across the tape, others romped over easily and pacing bunches scorched along. The usual foolish, senseless crowd blocked the course, crowded inanely out into the path of the riders and even when ridden down and knocked about in the dust some of them persevered until even the police could not but notice the condition of affairs. But threats and entreaties were in vain and half a dozen wheelmen were thrown heavily by collision with the mob.

Summary

Ulbricht broke the Santa Monica road race record of 57:01, made by him last year, making the seventeen miles in 49:29.

Race winner Emil Ulbricht (1864-1900) was as an agent for Thistle Bicycles. Some reports referred to him as “The German” since he was born there. The most famous Thistle racer was world champion Tillie Anderson.

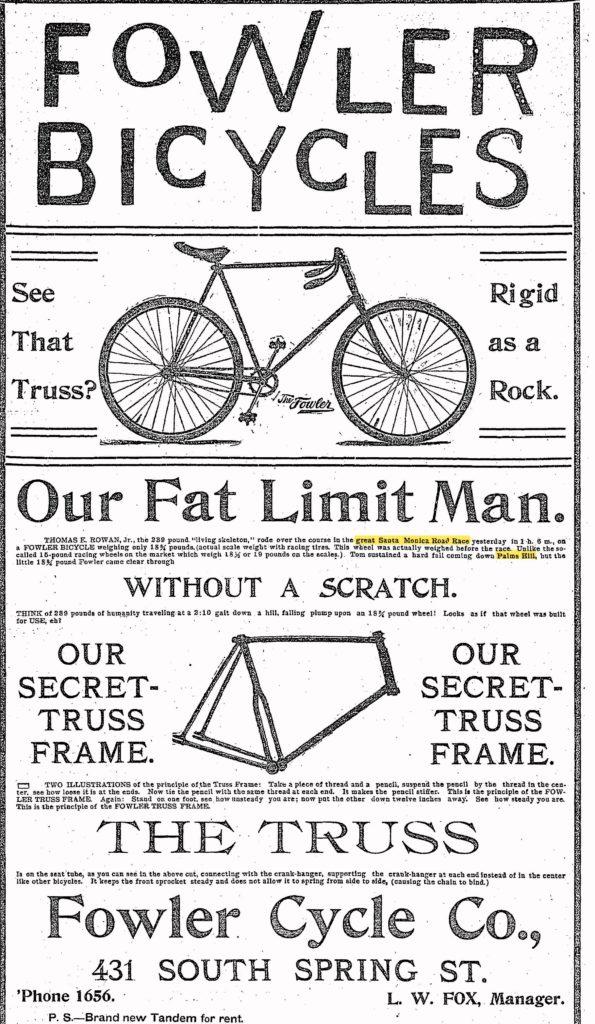

The 1895 Santa Monica Race’s slowest rider, or “limit man” (see glossary), Thomas E. Rowan, Jr., was featured in the Herald article’s illustration (also found at the top of this page) and in a Fowler Bicycles advertisement next to the Herald article. Fowler touted the 18 ¾ pound bike’s strength for holding up to the 239-pound Rowan, even when “Tom sustained a hard fall coming down the Palms hill.”

Luthor Ingersoll’s Century History, Santa Monica Bay Cities (1908) looked back on the bicycle phenomenon – including the Santa Monica Race:

During the rage of the cycling fever the annual road race on July Fourth was the leading event of the year to bicycle racers. On those days Santa Monica was crowded with dusty, sweating, red-faced youths, in the most abbreviated of clothes and with the most enthusiastic of yells, greeting each man as he pedaled into view. A bicycle path to Los Angeles was constructed, bicycle clubs and a club house flourished, and the Southern Pacific spent thousands of dollars on a bicycle race track and grand stand which was probably the poorest investment that the S. P. railway ever made, for almost before it was completed the bicycle craze died out as suddenly and as completely as the various spells of roller skating, which sweep over the country and vanish into space. The Athletic Park, as it was christened, was used for several years for ball games and sports of various kinds, but it has now become a thing of the past.”

(Ingersoll, pp. 307-308.)

Articles about the Santa Monica Race (and other races) include:

June 22, 1895, Los Angeles Times (map shown above)

July 5, 1895, Los Angeles Herald (excerpted above)

December 7, 1930, Los Angeles Times (“Many a local wheelman still remembers the annual road races form Los Angeles to Santa Monica, inaugurated one Fourth of July in the early ’90s” “The first ‘century run,’ as the 100-mile ride was called, was a yearly event here, as in other parts of the country. The trip had to be finished in not more than twenty-four hours and the recognized course extended from Los Angeles to Pomona, thence to Santa Monica and back to the city.” “Annual relay races from Los Angeles to San Diego . . . were important occasions.” “Wheelmen contended for such valuable prizes as pianos, furniture, bicycles, medals, jewelry, etc.”)