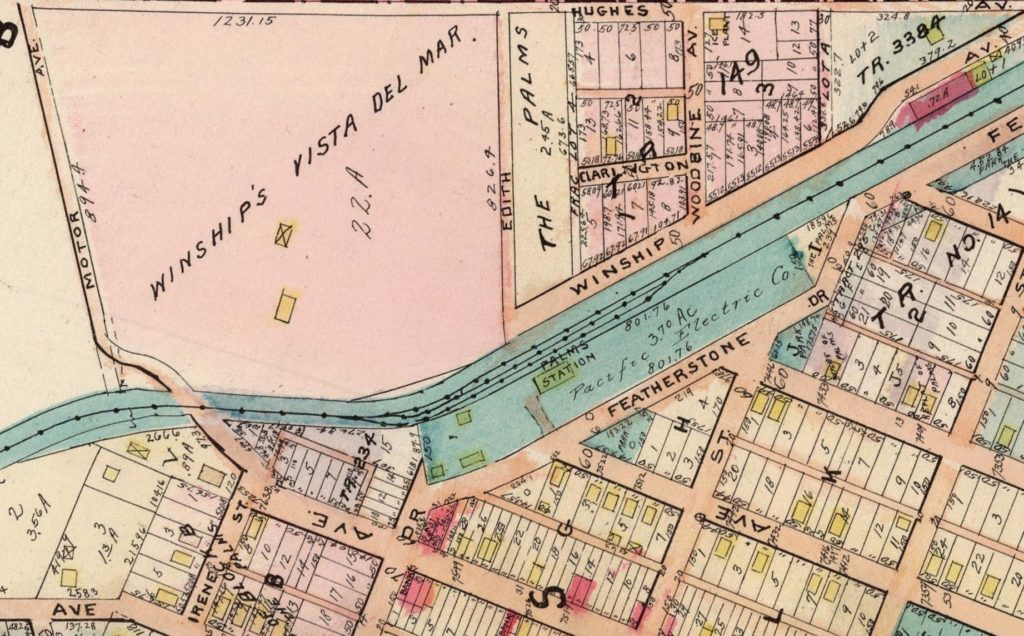

Winship’s Vista del Mar is the largest undivided single-owner piece of The Palms subdivision. The Palms’ first developers named it Vista del Mar, then Charles Winship, who held it from 1898 through 1904, put his name before “Vista del Mar,” making it Winship’s Vista del Mar, which it remains. Wealthy industrialist Thomas Hughes had his country home there from 1906 until about 1922, but his name stayed only on a nearby road. The Jewish Orphans Home of Southern California – now named Vista Del Mar Child Care Services – bought the site in 1924 renaming itself “Vista Del Mar” when it moved there in 1925. After land was sacrificed to widen and reroute Motor Avenue and for the Santa Monica Freeway, Vista del Mar covers 16 acres.

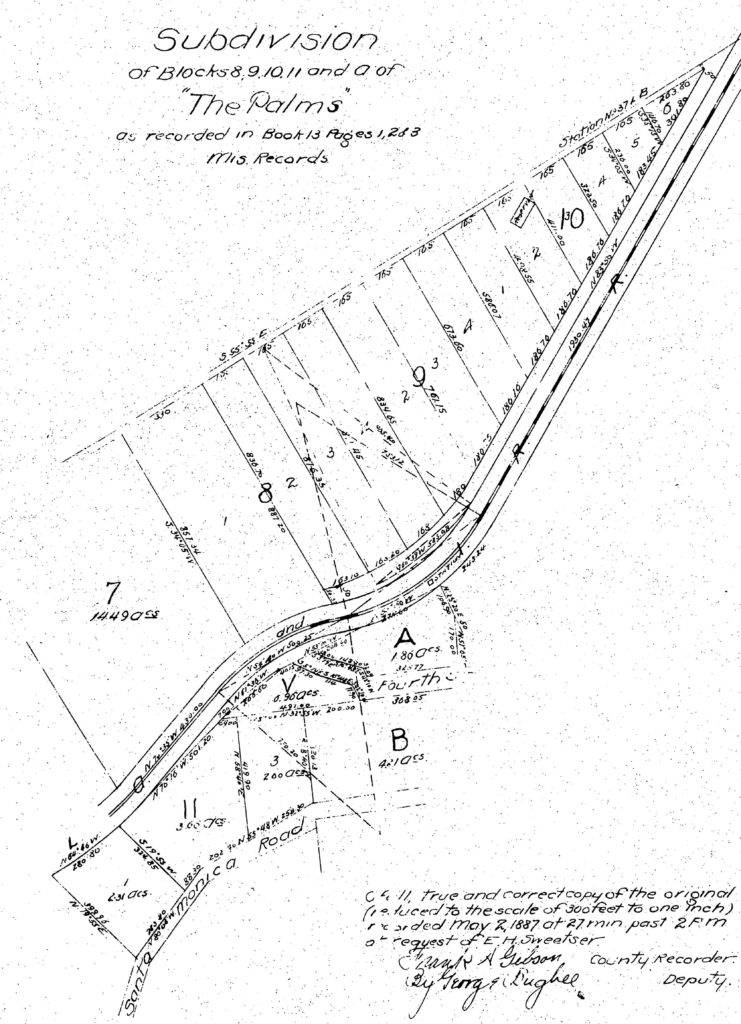

Sweetser resubdivides part of The Palms (1887)

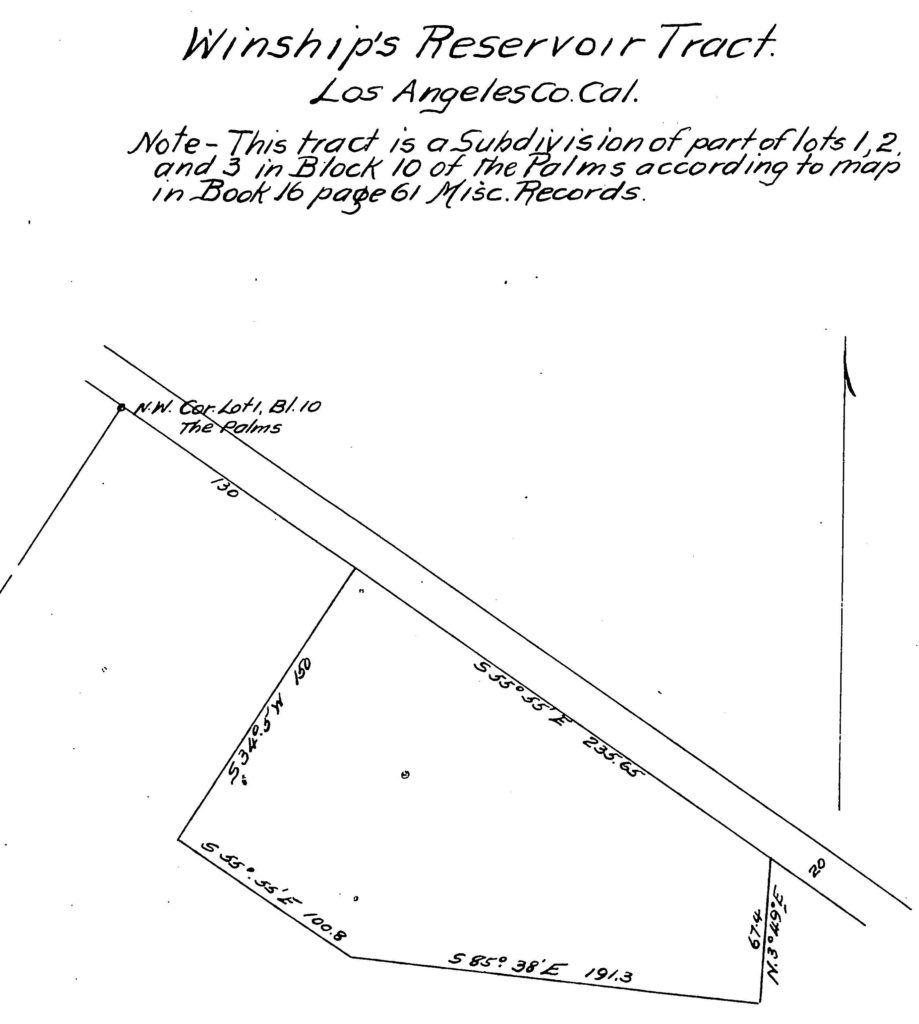

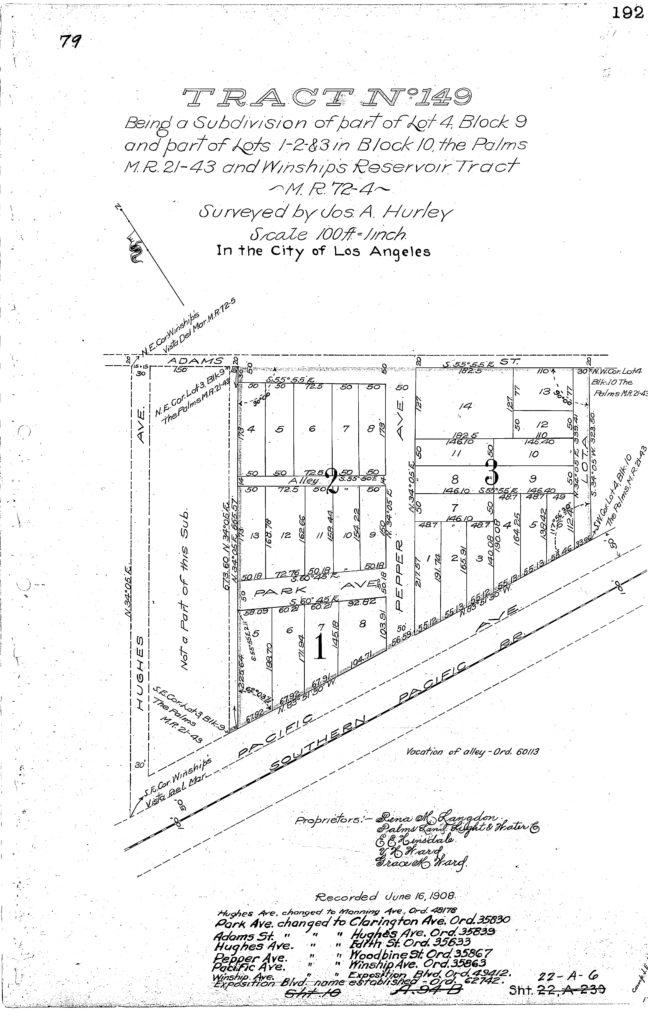

Months after The Palms was subdivided from the former Ballona Rancho, one of the three promoters, Edward Healey Sweetser (1844-1916), resubdivided Blocks 8, 9, 10, 11 and A into smaller lots. He carved Vista del Mar from Lots 8 and 9.

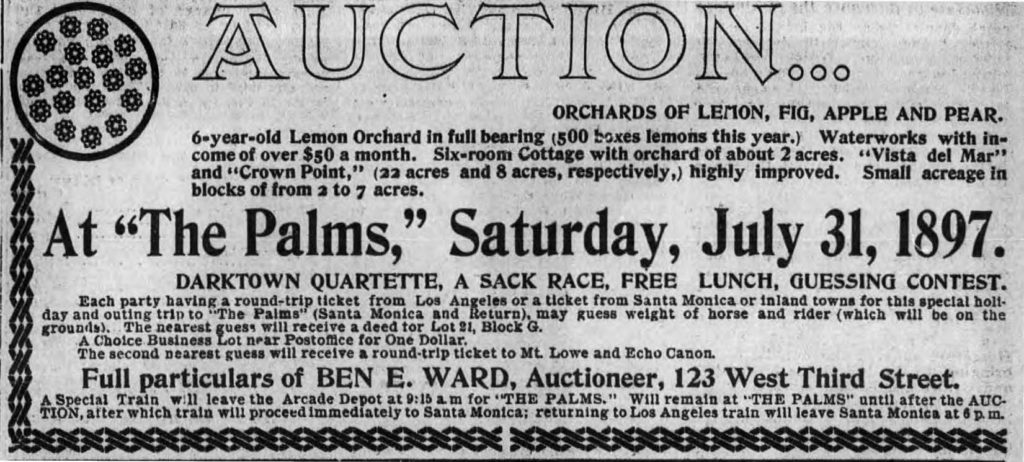

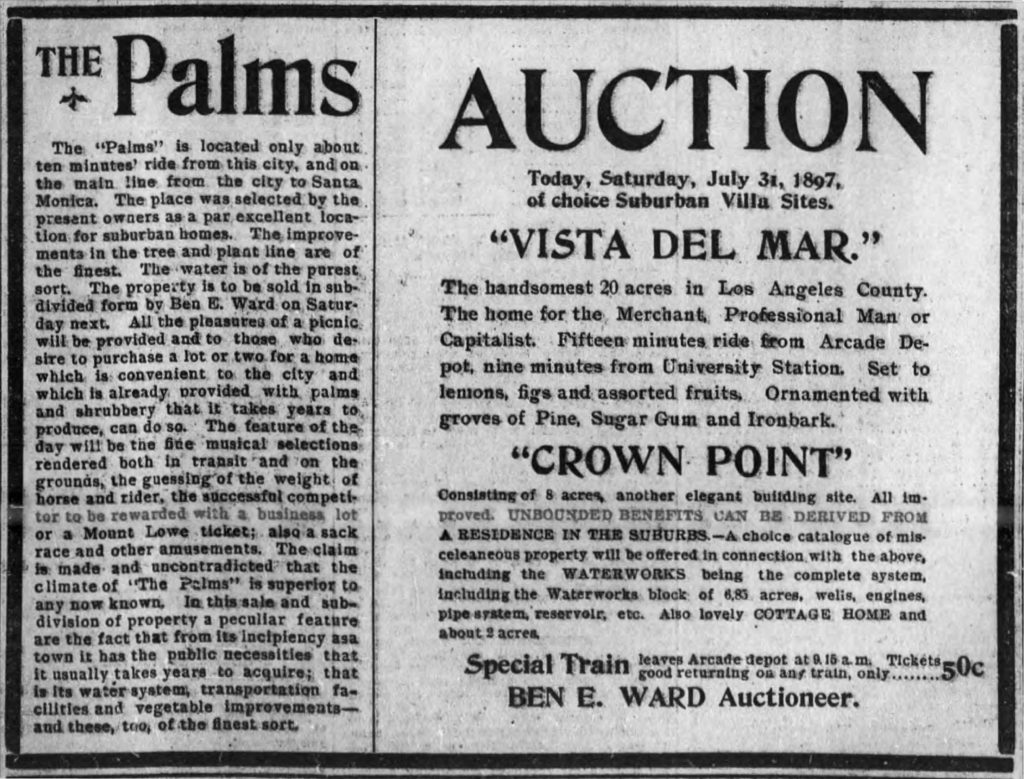

An Auction: Vista del Mar & Crown Point

Inducements to attend the July 31, 1897, auction where Vista del Mar would be offered included a guessing contest to win a free lot and another for a dollar.

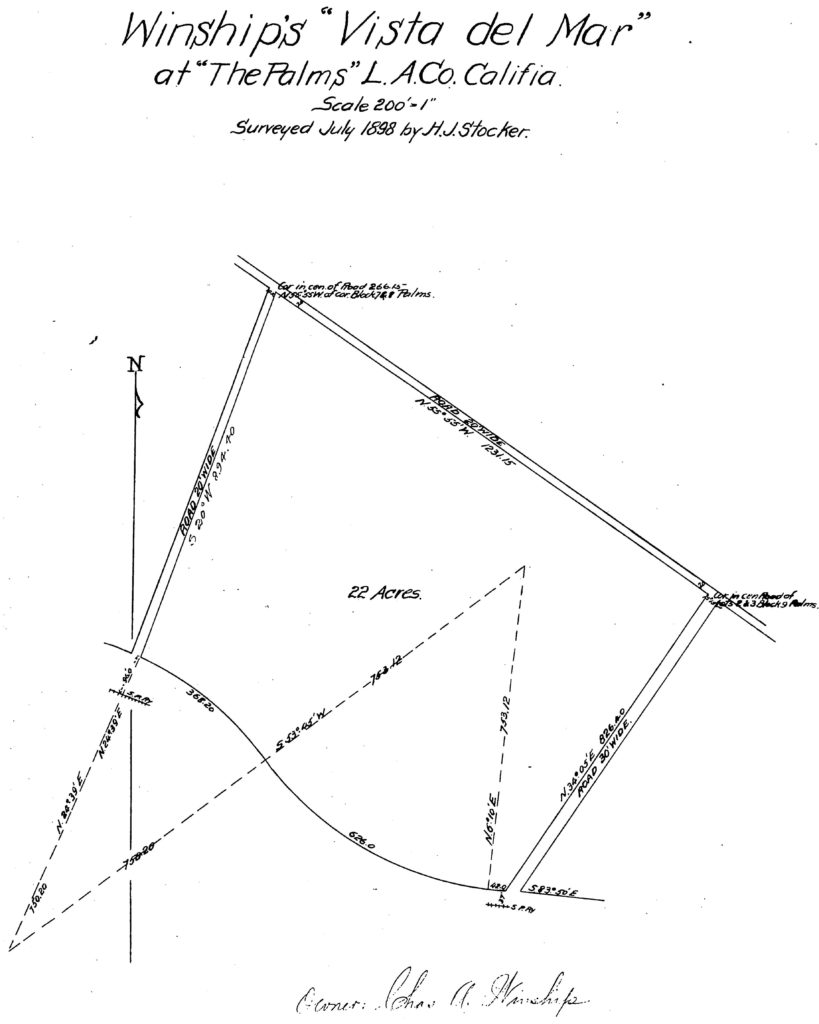

Sweetser advertised Vista del Mar at both 20 and 22 acres. The advertisement above offers up for auction “‘Vista del Mar’ and ‘Crown Point,’ (22 acres and 8 acres, respectively,) highly improved.”

Three days later, an advertisement called Vista del Mar “The handsomest 20 acres in Los Angeles County. The home of the Merchant, Professional Man or Capitalist.” On the Los Angeles & Independence Railroad, it was “Fifteen minutes ride from Arcade Depot” and “nine minutes from University Station” (the railway’s station at Vermont Avenue). The land had “lemons, figs, and assorted fruits” and was “ornamented with groves of Pine, Sugar Gum, and Iron Bark.”

Winship Buys (1898)

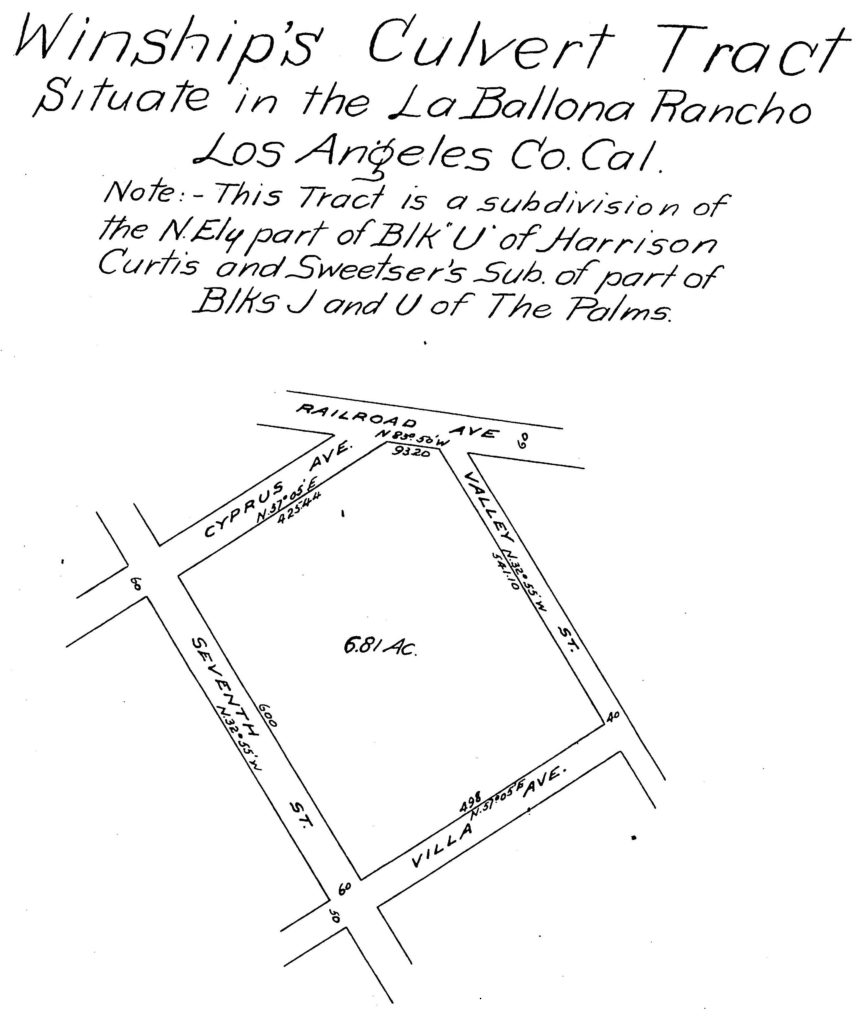

Whether Vista del Mar sold at the Summer 1897 auction is unknown. However, newspaper reports do show that in 1898, Charles Albert Winship (1855-1920) became the owner of Vista del Mar and various other parcels, including The Palms’ water works. On February 24, 1898, The Evening Express reported Mr. E. H. Sweetser [transferred] his beautiful tract at the Palms, called The Vista Del Mar, containing over [20] acres, planted to oranges and deciduous fruits, to a Minneapolis gentleman, who intends to build a fine home thereon and to highly improve the property.” Maybe Mr. Winship came to Los Angeles via Minneapolis (he was born in Connecticut). Or maybe the Evening Express confused Winship with the Minnesotan land buyer in the same article. On March 22, 1898, the Los Angeles Times reported Winship’s purchase, adding that Edward Sweetser’s wife, Elisabeth Leona (Borchers) Sweetser (1852-1940), was also a seller: “E H Sweetser and Elizabeth L Sweetser to Charles A Winship, lots 6 to 9, 20 and 21, block U. Harrison, Curtis and Sweetser’s Subdivision of part blocks J and U, The Palms; lots 9 to 12, block U, all of block 8, lots 1 and 2, block 9, and part of block 7, also part Lots 1, 2, 3, and 6, block 10, the Palms, including entire water system on said property . . ..”

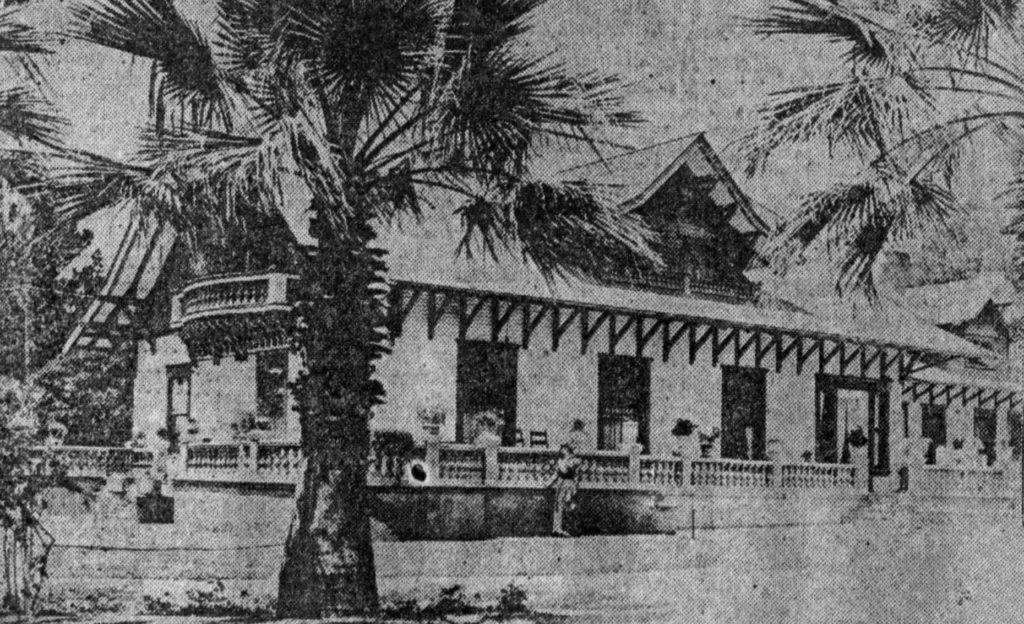

Vista del Mar house designed by top architects (1898)

Winship moved quickly to have a house built at Vista del Mar. On April 28, 1898, the Evening Express, detailed a building agreement: Cahill & Raney contractors would build a house and barn designed by architect “Dennis P. Farwell” by July 1, 1898, at a price of $2,941. Apparently “Dennis P. Farwell” is a typo; the article should have said “Dennis & Farwell,” since “Dennis & Farwell was a Los Angeles architecture firm formed in 1895 by architects Oliver P. Dennis (1858-1927) and Lyman Farwell (1864-1933).” The Online Archive of California reports that they designed homes for Henry Fisher, Redlands (1897); Erasmus Wilson, West Adams (1903); John Cline, West Adams (1903); and Rollin B. Lane, Hollywood (1909) (now the Magic Castle nightclub).

Architecture enthusiast Michael Locke tells more about the Dennis & Farwell firm and provides photographs of their projects:

Architects Dennis and Farwell designed many important buildings in Southern California during a partnership that lasted from 1895 until the mid teens. Lyman Farwell attended the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, graduating from the architecture program in 1887. (MIT established the first architecture school in the United States in 1865). After graduation, Farwell studied at the famous Ecole des Beaux-Arts in Paris, France. Oliver Perry Dennis served as a draughtsman for the firm W.H. Dennis & Company; the firm designed a number of notable business buildings in Minneapolis. He moved to Los Angeles in 1895 and formed a partnership with Lyman Farwell under the firm name of Dennis & Farwell.

The firm designed many important commercial buildings including the Fay, Merchants’ Trust, Columbia Trust, and Iowa Buildings, the Fifth Street Store, Chickasaw Hotel, Science Hall of Los Angeles High School, the Salvation Army Home as well as the Hollywood Hotel and the Hotel Napoli at Naples.

(Michael Locke, flickr.)

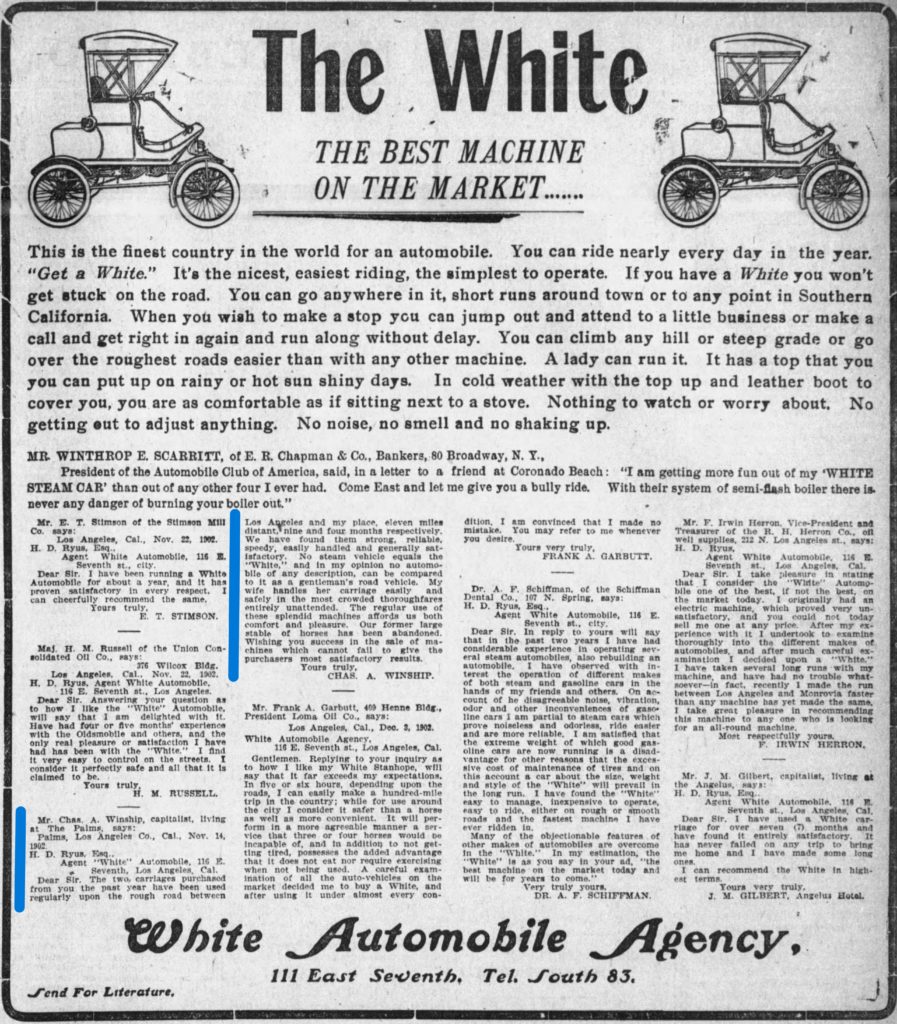

Winship name attached to tracts (1898-1899)

In an October 1999 telephone interview, Janice (Brooks) Arner (1908-2000) told this site’s author that her parents, John Columbus Brooks (1865-1939) and Lila Louise Stinton (1879-1929) met at the Winship ranch where her father was the horse trainer and her mother was a housekeeper. And in the January 1903 testimonial above, Charles Winship wrote his two steam-powered “carriages purchased … the past year have been used regularly upon the rough road between Los Angeles and my place, eleven miles distant.” “Our former large stable of horses has been abandoned.” Mr. Winship abandoning his stable would have put Janice’s father John out of work only eight months after her parents wed on April 30, 1902. Janice’s father found other work, though, with the 1920 and 1930 censuses showing John working as a teamster on county roads – in the days when horse drawn wagons oiled dusty dirt roads. Mr. and Mrs. Brooks raised their family down the street from Winship’s Vista del Mar, at 3613 Motor Avenue. That would also be down the street from Lila’s brothers’ sister-in-law Frances Louise “Frankie” (Laforge) King (1870-1966) whose farm was developed into Cheviot Hills. Two of Lila’s sisters married two of Frankies’ brothers back in Iowa (whence many Palmsians came). Lila’s sister Esther Florence Stinton (1860-1930) married Webster William Laforge (1851-1921) and sister Emily Elizabeth Stinton (1863-1929) married Emerson “Doc” Laforge (1857-1941). Frankie and A. L. King built an impressive house at the head of Motor Avenue in 1914 and would be friends with the new residents at Winship’s Vista del Mar after the Winships moved away.

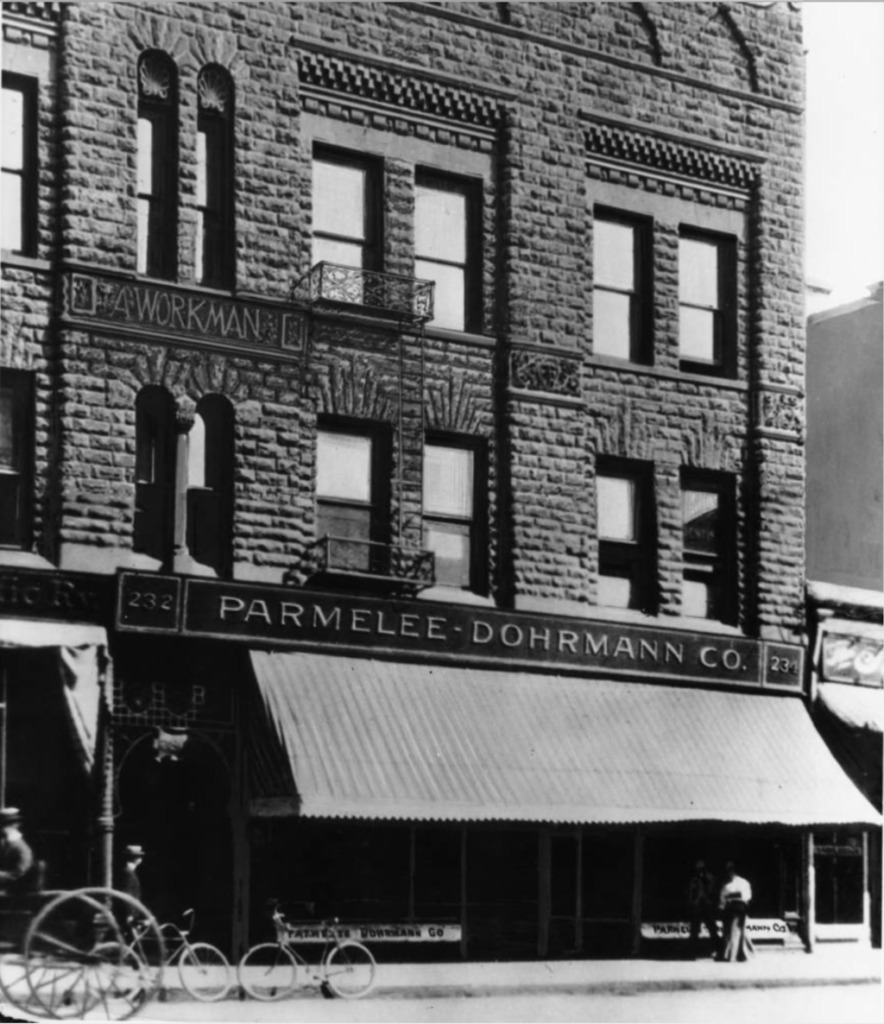

Winship trades out for Workman Block (1904)

In 1904, Winship sold his Vista del Mar properties to A. W. [Alonzo Willard] Rhodes (1870-1937), manager and principal owner of the United Investment Company. The Los Angeles Evening Express (Jan. 30, 1904) reported that A. W. Rhodes sold the Workman Block (230 to 234 South Spring Street) for $200,000, for which Winship “gave in part payment . . . his magnificent home place at The Palms, known as Vista del Mar, and valued at $50,000.” Days earlier, the Los Angeles Times (Jan. 24, 1904) had reported that the Vista del Mar sale included “twenty-two acres highly improved, together with a handsome twelve-room two-story combination frame and stone dwelling, at $40,000.” Alfred Henry Workman and Henrietta S. Workman had sold their eponymous block to United Investment in 1902 for $170,000. (L. A. Express, June 13, 1902.)

Thomas and Carrie Hughes buy Vista del Mar (1906)

On September 1, 1906, Los Angeles Herald reported Thomas “Tom” Hughes (1859-1923), had bought Vista del Mar, presumably from A. W. Rhodes’ United Investment Company: “the well known oil operator, paid $50,000 for the Winship ranch at Palms. The tract embraces 24-acres which will be subdivided and improved in high class style. The acreage is convenient to the Los Angeles-Pacific Railroad.” The Herald’s prediction was wrong: unlike most of the surrounding area, the acreage was not subdivided. Instead, Tom Hughes and his wife Caroline E. “Carrie” (Sweet) Hughes (c. 1860-1918) operated it as a farm. Notables of the Southwest (L. A. Examiner, 1912) indicates she was married before, reporting that Mr. Hughes “was married in June, 1881, to Mrs. Perry Mosher in New Mexico.” (The marriage may have been to a John M. Mosher.) The 1910 Census shows Carrie and Tom Hughes living in Ballona Township (a subdivision of Los Angeles County) along with Norita Kintaro (1879-?), Sakujiro Yoskikawa (1882-?), Kerjiro Watanabe (1870-?) (listed as farm workers/gardeners) and Ida Tam (1883-?) (the farm’s manager).

The year before he bought Vista del Mar, the Los Angeles Times profiled Thomas Hughes and his sash and door company, Hughes Manufacturing Company, highlighting their successful fight against unionization: “The splendid industrial results that are achievable in manufacturing in Los Angeles when the industry is not saddled with unionism are well exemplified by the large new plant which has just been completed by the Hughes Manufacturing Company of this city.” (L. A. Times, May 14, 1905.) Several months later, Hughes and his company were extolled for making cots in the immediate aftermath of the 1906 San Francisco Earthquake. (L. A. Times, April 23, 1906.) Thomas Hughes would be the subject of several biographies during his lifetime: Men of Achievement (L. A. Times, 1904); Out West Magazine (1909); Notables of the Southwest (L. A. Examiner, 1912); and Los Angeles, From the Mountains to the Sea (American Historical Society, 1921) (largely repeating Notables of the Southwest). Highlights from these sources include Tom Hughes moved to California from his birthplace in Pennsylvania, via Kansas and New Mexico, where he picked up skills in a planing mill.

After working a year, he invested his capital, five hundred dollars, in two machines and went into the sash business for himself. He had success and in 1896 organized the firm of Hughes Brothers, changing this in 1902 to the Hughes Manufacturing Company, of which he is president. His plant today represents a value of $700,000, employs five hundred men and is considered the largest of its kind in the West.

(Notables of the Southwest, L. A. Examiner, 1912.)

He also is active in oil production, having with Ed. Strassburg organized the American [Crude] Oil Company, one of the first formed in the Southwest. This company has been a steady producer, and has been one of the most conservative and profitable. He has helped organize other companies. He is the owner of considerable property in Los Angeles and in the adjacent cities of Southern California.

Mr. Hughes is a purist in business and politics, and although he has never held public office has

done much to aid the city and keep its politics clean.

He is an Elk, a member of the Driving Club, Los Angeles Country Club, San Gabriel Country

Club and former president of the Union Club.

Thomas Hughes would also be California Governor William D. Stephens’ (1859-1944) campaign manager and be appointed to the Los Angeles Harbor Commission by Mayor Woodman in 1917.

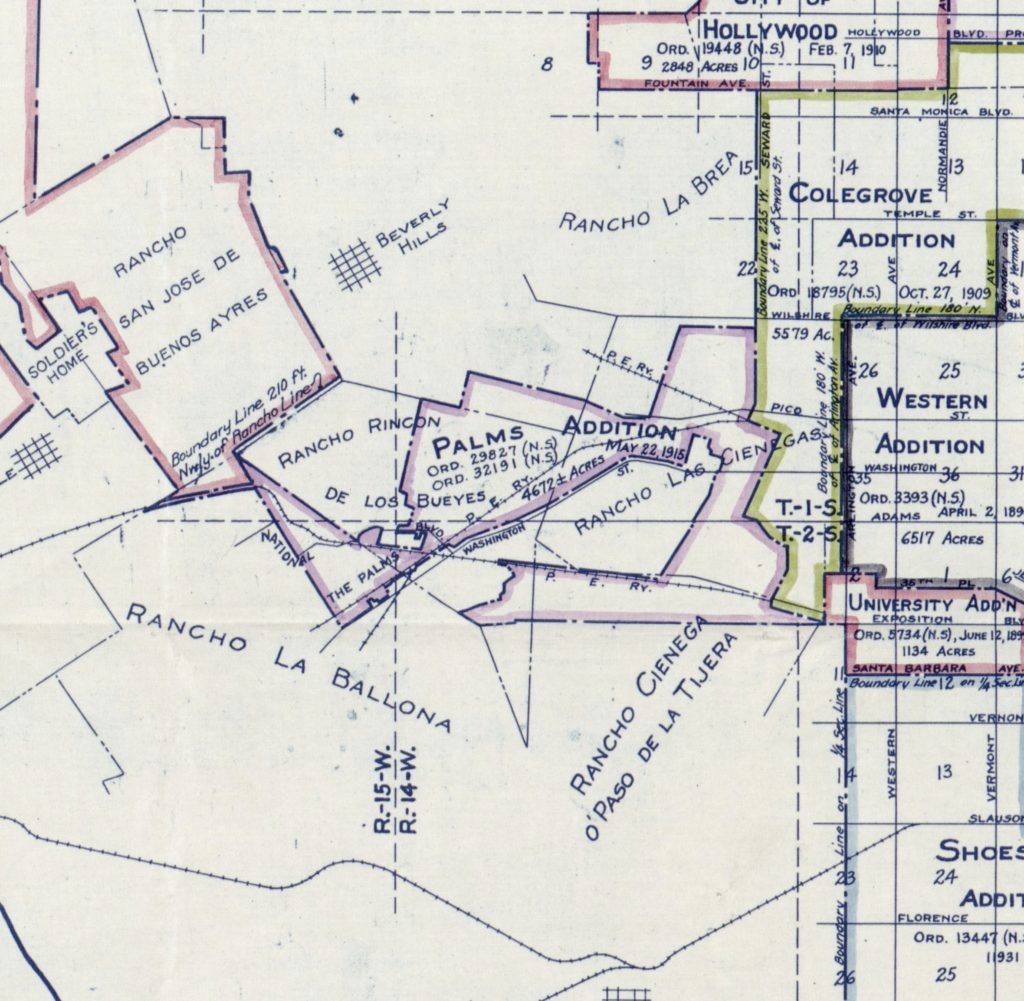

The Palms becomes part of Los Angeles and street names change (1915)

Winship’s Vista del Mar (along with much of “The Palms” subdivision) was included in the land annexed to Los Angeles through the May 22, 1915, “Palms Addition.”

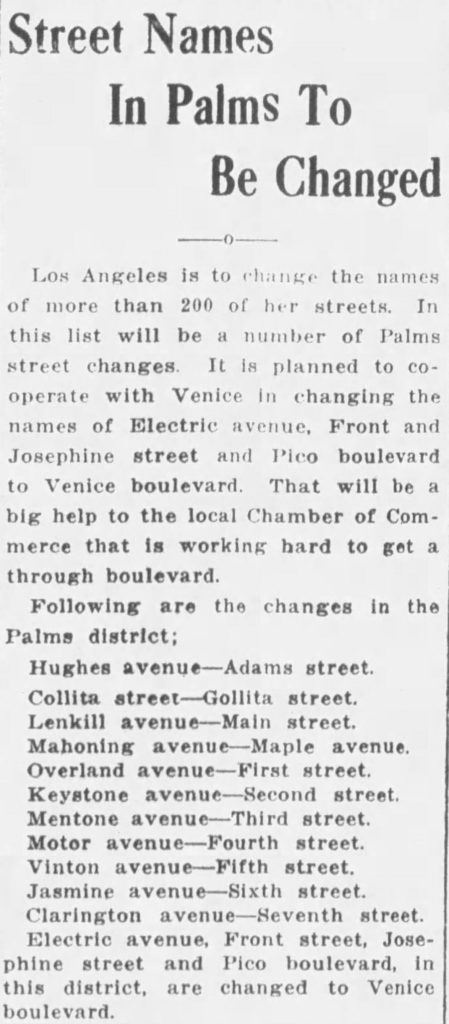

In 1916, soon after the Palms Addition, Motor Avenue was renamed from Fourth Street. The next year, on January 25, 1917, the name Hughes Avenue moved from one street to another. It had applied to a north-south street on the east edge of Winship’s Vista del Mar; that street was rechristened Edith Street, which it remains. At the same time, Adams Street (the roadway on the northern edge of Thomas Hughes’ property) became Hughes Avenue. (It would become Manning Avenue on March 11, 1924.) A month later, on February 27, 1917, Valley Street (from Exposition Boulevard south to Washington Boulevard) took the Hughes name, also becoming Hughes Avenue, which it remains.

Carrie Hughes Dies and Thomas Hughes Remarries

Carrie Hughes died in April 1918 after a two-year illness. The Evening Express reported that “Mrs. Hughes, through her activities during her 34 years’ residence in Los Angeles, became widely known in social and club life. She was a member of the Ebell and Friday Morning clubs, the Pine Forest Card club for 16 years and of the National Sunshine club.” (Evening Express, April 24, 1918.) At her funeral, pallbearers included her neighbor Abraham Lincoln King (1866-1927) (a subdivider, but not developer, of Cheviot Hills) and Los Angeles Mayor Frederic Thomas Woodman (1872-1949). (L. A. Times, April 25, 1918.)

On December 24, 1918, eight months after Carrie’s passing, Thomas Hughes married Gertrude Cullen (c. 1879-1958), who had been married (and widowed) twice before. Back in 1896, Gertrude had married Roydon Wheeler Ozmun, Sr. (1875-1905), who died on April 30, 1905, of a “paralytic stroke” after a “nervous break-down,” leaving behind Gertrude and two young boys. (Anaheim Gazette, May 4, 1905.) One account had Mrs. Ozmun inheriting the entire million-dollar estate – well over $35 million in 2023 dollars. (Chico Daily Enterprise, May 3, 1905.) By August, Gertrude had married attorney Byron Lee Oliver (1872-1909). That union lasted until May 1919, when Mr. Oliver was stricken with typhus fever while he and Gertrude were travelling with Tom Hughes in Chiapas, Mexico (where Hughes had extensive lumber interests). The Los Angeles Times reported that Oliver died in Hughes’ arms. (L. A. Times, May 6, 1919.)

Sadly, after six months this last marriage exploded onto the front pages of newspapers. Mrs. Hughes sued to enforce “an alleged prenuptial contract through which she expected to receive $500,000” from the “millionaire politician and Harbor Commissioner.” (L. A. Times, May 6, 1919.) Coming on the heels of a sensational bribery trial of Hughes’ friend, Los Angeles Mayor Woodman (who had been exonerated), Hughes contended some of the same people were behind this action against him:

“The trouble began about the time the grand jury began investigating the Woodman bribery case,” says Mr. Hughes. ”When Mrs. Hughes and her sister, Mrs. Minnie Heffner were greatly wrought up over the fat that I was called to testify before the grand jury. My wife said it would ruin her social standing. Back of the whole trouble is the fact that an attorney has been ‘keeping company’ with my niece, Miss Maude Heffner. It was my niece who took the stand in the Woodman case and contradicted my testimony. I am thoroughly convinced that this lawyer (Mr. Hughes named him) was keeping company with Miss Heffner for no reason other than that of ‘getting something’ on me to use in the Woodman trial. I firmly believe he was assisting the prosecution. I cannot believe otherwise, for he is a man of about 40 years, while she is a slip of a girl, 22 years old.

(L. A. Times, May, 6, 1919.)

Three or four weeks ago when the Woodman case began to loom up I went out to my country home at The Palms to look after the harvesting of the crops. My wife did not accompany me. I have been staying out there and at the Union League Club since. We had no quarrel, and I did not desert her. She is supposed to live where I live, and she agreed before our marriage that she would live at The Palms if I would spend several hundred dollars remodeling the house. I had it fitted to suit, but she insists on living at her home in Los Angeles, so I made my home there too. After we were married she went to the Palms and hauled all my furniture to her residence.

Mrs. Hughes’ allegations were laid out in a decision by the California Court of Appeal (holding the prenuptial unenforceable because it was not in writing):

It is alleged in the amended complaint that the defendant is seventy-two years of age, and possesses property of the value of more than five million dollars. Between April 30 and December 24, 1918, the defendant importuned plaintiff to marry him, and offered, if she would do so, to convey to her property worth six hundred thousand dollars. To all these proposals the plaintiff turned a deaf ear. While the plaintiff was absent from the state of California, the defendant, pursuant to a design, and intention to compel the plaintiff to marry him, moved himself and his personal belongings into the residence of plaintiff in Los Angeles, and there took up his abode. He caused to be inserted and published in various newspapers statements to the effect that the plaintiff and himself were to be married about Christmas time, and caused copies of a photograph of plaintiff, which he took without her knowledge or consent from her residence, to be published in connection with these notices.

(Hughes v. Hughes (Sept. 7, 1920) 49 Cal.App. 206, 207-208.)

Finally, so it is alleged, the defendant, by pretending he was seriously ill, induced the plaintiff to go to him at Santa Barbara, where he then was. On her arrival there she found that the defendant was not ill, but had so represented himself, in order to cause her to come to him. She then learned for the first time of the stories the defendant had published in the newspapers concerning the approaching nuptials. She discovered that he had also invited guests to be present at a certain time, had provided a wedding dinner, secured a marriage license, and had arranged for a minister to be present to perform the wedding ceremony. Plaintiff still persisted in her refusal to marry defendant. He thereupon stated that he would be ruined politically, that his social standing would be impaired, he would be disgraced and humiliated, and his opportunity to represent the state of California in the United States Senate, which he asserted had been entirely arranged and determined upon between himself and the Governor of the state, would thereby be lost to him. He promised that if plaintiff would marry him he would give her, as her own, a valuable diamond ring, a diamond stickpin, an ermine coat, and an automobile. At the same time defendant orally reiterated his promises that, if plaintiff would marry him, he would immediately after the marriage convey to her the real property formerly agreed to be given to her, and would erect an imposing residence on land owned by plaintiff. He promised, also, to purchase other land for her, and erect thereon an apartment house, at a cost of one hundred thousand dollars. He further agreed to pay off and discharge a sixty thousand dollar mortgage upon property belonging to the plaintiff.

After Mr. Hughes’ countersuit and Mrs. Hughes’ appeal (favorable to him), the couple reconciled in 1921. (Santa Ana Register, March 25, 1921.) On March 15, 1922, they received a passport to travel throughout Europe; they returned via Cherbourg, France, arriving in New York City on October 6, 1922.

When Thomas Hughes died on December 12, 1923, his obituary appeared throughout the state and beyond.

Vista del Mar Health Farm promoted for site (1922)

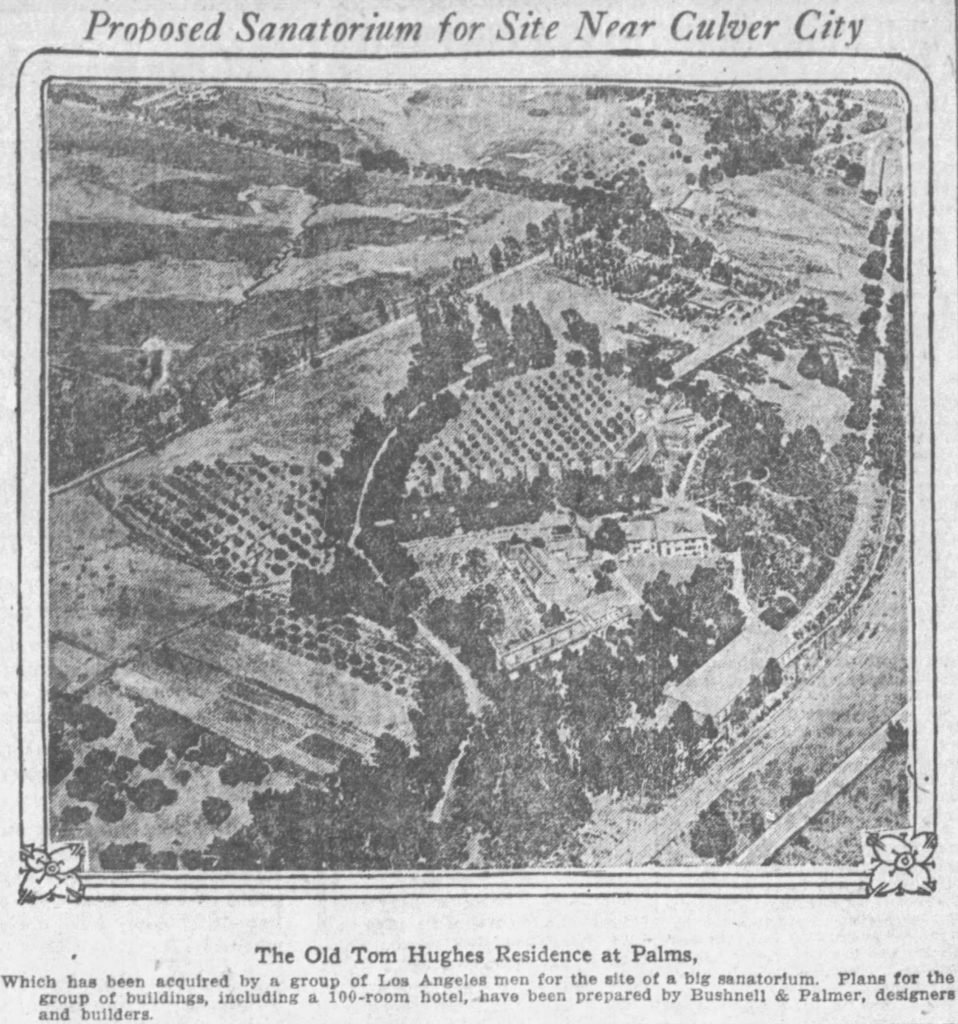

In 1922, insurance salesman Thomas S. Brown (1881-1927) was selling shares in the Vista del Mar Health Farm at the “Old Tom Hughes Residence.”

Plans for the development on the estate of the late Tom Hughes at Palms of a big sanitorium were announced yesterday by officials of the Vista del Mar Health Farm, Inc., a company recently organized for the purpose of carrying out this enterprise. The property, comprising twenty-two acres, fronting on National Boulevard, was acquired several months ago by George Smith, Dr. D. A. Ragland and associates for this purpose.

(L. A. Times, Oct. 8, 1922.)

Bushnell & Palmer, contractors and builders, have prepared plans for a group of buildings, including an administration building, a 100-room hotel, a big plunge with baths, garage and farm buildings upon which it is planned to expend approximately $250,000, according to Mr. Smith.

Advantage will be taken of the sulphur spring now on the property, and a bathhouse, with hydrotherapy and electrotherapy equipment, will be erected, and the most modern equipment for giving treatments will be installed.

The general and administrative offices and the laboratories will be incorporated in one building. It is planned to install a clinical laboratory, X-ray laboratory, metabolism laboratories and a laboratory with complete equipment for making physical examinations.

The hotel, as planned, will be two stories in height, and its capacity will be increased by the erection of a number of adjoining bungalows. In connection with the hotel will be erected scientific diet kitchens, as well as general kitchens.

The farm buildings will include a greenhouse for propagating vegetables, barns for the dairy herds and buildings for housing chickens, rabbits and squabs. The entire tract, not used for the sanatorium buildings proper, will be given over to farming.

Construction of the buildings will be started early next year, and it is expected to have the group finished by the end of summer. The company is headed by Dr. Albert Baff, president. George Smith is vice-president and general manager, and other officials and directors include: Dr. D. C. Ragland, treasurer and medical director; George W. Lichtenberger, director, and Clyde Doyle, attorney. In addition, there will be an advisory board of a number of well-known local physicians.

The Venice Evening Vanguard-Herald newspaper carried the identical story the next day, verbatim but for the headline and without the photograph. Possibly, both papers credulously accepted and reprinted the representations from the “Vista del Mar Health Farm, Inc. Parts of the story were a little wrong – such as the property “fronting on National Boulevard.” (National is across the railroad tracks.) Other parts were a lot wrong – like referring to the “late Tom Hughes.” Mr. Hughes was very much alive when these articles appeared.

Health Farm a fraud (1923)

Within a few months of the Vista del Mar Health Farm story, its promoter, Tom Brown, was jailed for embezzlement.

Tom Brown’s health farm lies amoulding in the grave while the wheels of justice go grinding on. But nobody is singing “Glory, Glory, Hallelujah, [least] of all Tom Brown, for he’s in the County Jail, charged with a violation of the Corporate Securities Act and embezzlement.

(L. A. Times, Jan. 22, 1923.)

Justice Scott held Brown to answer after testimony brought out the fact that he had sold nearly 2000 shares of stock to various persons, collecting the money and spending it upon himself.

Brown, according to witnesses, represented that he had an option on a lease at Palms, near Culver City. He showed papers and credentials proving that he was a fiscal agent for the Vista Del Mar Health Farms Corporation and stated that the company was to erect a health farm at the new location. But, say the complainants, he forgot to mention that he himself was virtually the company and had neglected to get a permit to sell stock of any kind.

He did, however, succeed in selling to H. A. Ragland of Los Angeles, 850 shares of stock and to Doctor A. J. Babb 1750 shares. Brown also supplemented this amount with $1750, which Dr. Babb says he gave Brown for current expenses during the sales campaign.

But instead of for the health farm, the plaintiffs say, their money went for diamonds and jewelry. So they went to [Deputy District Attorney] McClelland, obtained a complaint, and haled him to court.

As for the supposed purchase of the property, apparently there was only a lapsed option to buy, which had “expired and had been disposed of to other parties.” (Fresno Bee, Jan. 31, 1923, “Former Taftian Is Under Arrest in the South.”)

It was not the first time insurance broker Thomas S. Brown was accused of embezzlement, and it would not be the last. In January 1921, Los Angeles police, together with private Pinkerton’s detectives, had arrested him and he was charged with “having embezzled a considerable sum of money from the Pacific Mutual Life Insurance Company, by which he was employed.” (L. A. Times, Jan. 22, 1921.)

Brown would not be jailed for embezzlement again, although he was once more accused. In 1927, he “was charged with the embezzlement of $400 declared given him by Margaret Grell for investment.” (Bakersfield Morning Echo, Jan. 16, 1927.) Another account had it that “Brown had been sought on a fugitive warrant for six weeks charged with embezzling $700 from Mrs. Margaret Grell last November.” (L. A. Times, Jan. 16, 1927.) The news stories vary as to whether he held “a squad of police and sheriff’s deputies at bay for more than an hour” or whether he had an “automatic pistol under his pillow.” In any event, rather than face charges, he fatally poisoned himself.

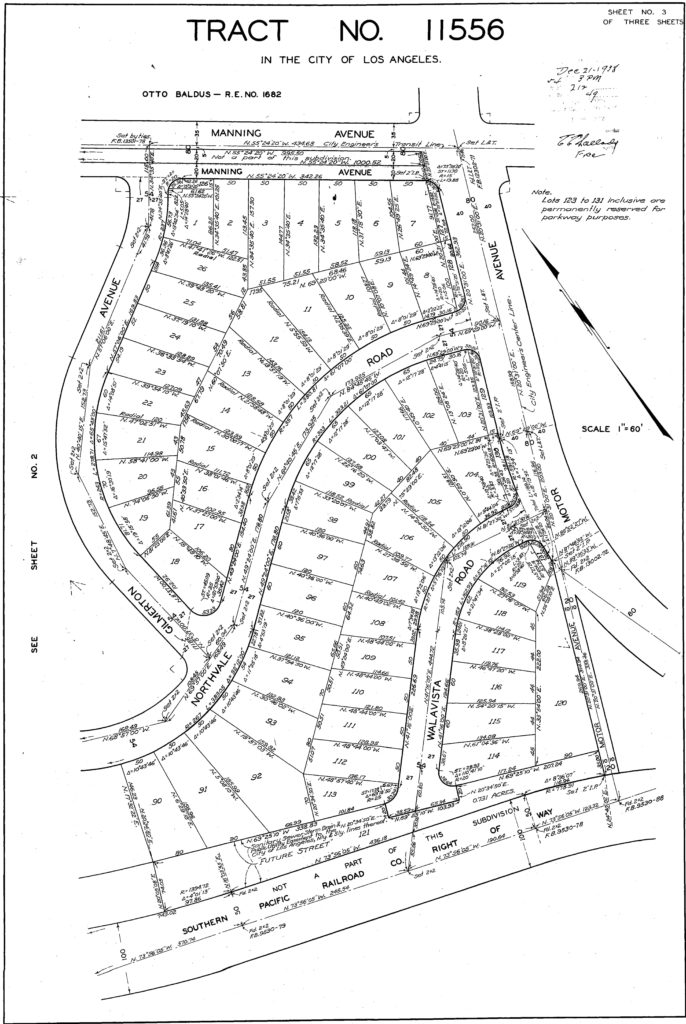

Frans Nelson & Sons plans to subdivide (1923)

In September 1923, developer Frans Nelson & Sons’ engineer E. E. Mix told the Los Angeles City Council that, along with subdividing Cheviot Hills, they had “plans for the development of Winship’s Vista Del Mar subdivision … .” (Los Angeles City Council Minutes, September 14, 1923.) Those plans, while not fraudulent like Mr. Brown’s, plainly fell through.

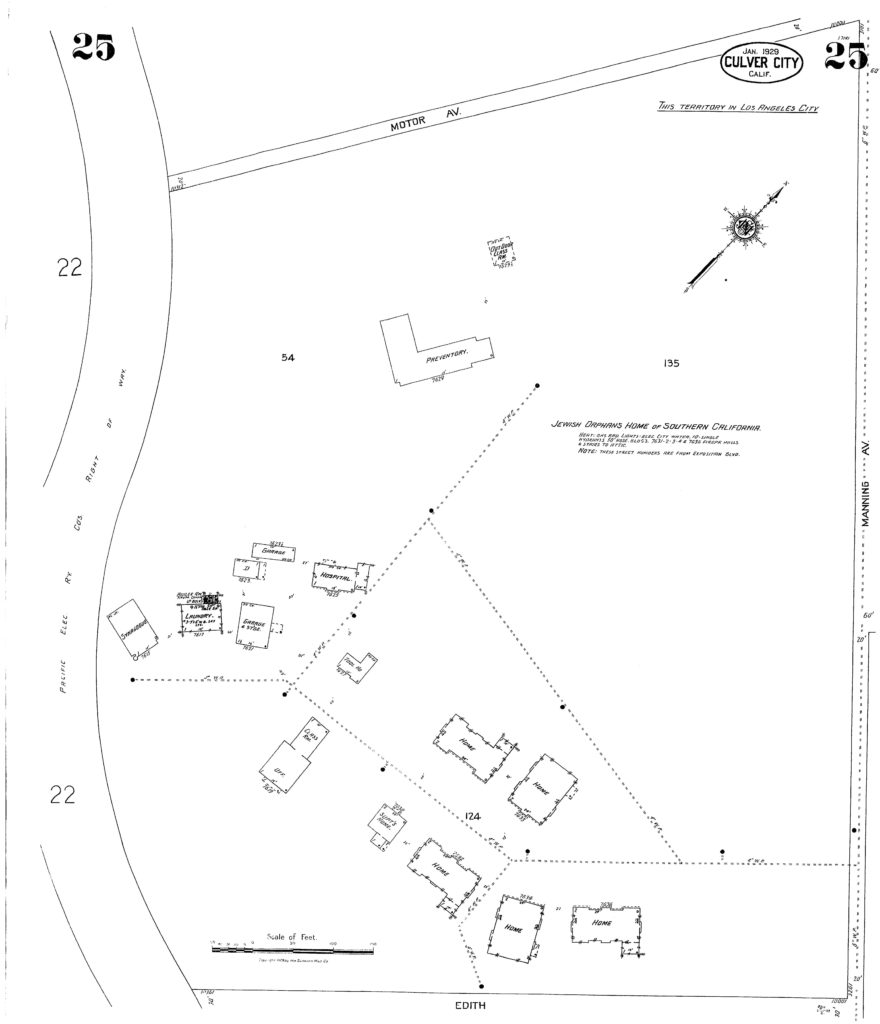

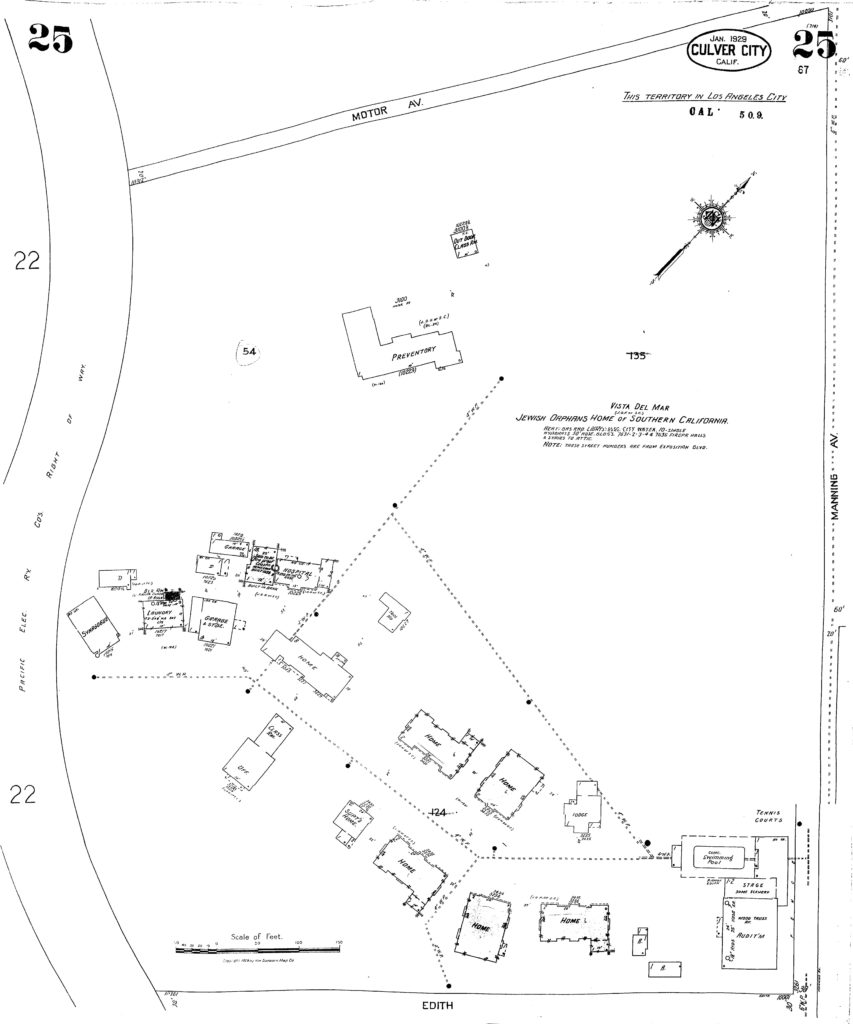

Orphanage buys (1924) and moves in (1925)

This website will not dive deeply into the history of Vista Del Mar Child Care Services (earlier called The Jewish Orphans Home of Southern California) especially since it has published its own story: A Short History of Vista Del Mar Child and Family Services. However, given the site’s focus elsewhere on Alexander Hamilton High School (and through access to the Federalist newspaper archives), some connections between the institutions will be noted. For instance, Anna Mae Mason (1901-1983), who taught physical education at Hamilton from 1938-1966, submitted her Master’s Thesis in 1940, in which she reported 2.7 percent of Hamilton’s enrollment came from Vista Del Mar. She described it as follows:

It is composed of several attractive, comfortable residences constructed not as dormitories, but as fraternities where each group of students have specified duties and privileges, govern themselves and regard themselves as family units. Each residence has its house mother and the Home provides recreational, religious and hospitalization facilities. The training these students receive in their homes in self-discipline, self-management and practical democracy make them likable, respectable, admirable members of the student body. It will be noted by a comparison of percentages that

(A Study of the Pupil Personnel of Alexander Hamilton High School of Los Angeles, p. 25.)

students from the Home use English and not Hebrew as their usual means of discourse.

A March 1935 Federalist featured an interview with Vista Del Mar Director Joseph Bonapart (1889-1973). Mr. Bonapart participated in Hamilton events as late as the mid-sixties, retiring in October 1966, having served Vista Del Mar for 43 years. In 1936, Alexander Hamilton High School borrowed Vista Del Mar’s tennis courts when it competed with other schools. Hamilton football and basketball teams scrimmaged against Vista Del Mar teams. In 1937, the Federalist reported of the footballers, the “entire Del Mar squad consists of Hamilton students who each year organize a team of their own and play various schools in different leagues.” The Medical Arts Club visited Vista del Mar in 1948, touring the hospital learning from the nurse in charge about a nursing career while also seeing one of the homes, “new recreational lodge,” and swimming pool.

Among the buildings permitted in 1928 were a 14-room 127′ x 85′ L-shaped cottage and an outdoor classroom, designed by the Curlett and Beelman partnership (1922-1932). Only Claud Beelman (1884-1963) was listed on the November 14, 1928, permit for the 18 x 52-foot garage. Claud Beelman would become famous for his Beaux-Arts, Art Deco, and Streamline Moderne style buildings, many of which are on the National Register of Historic Places. His Eastern Columbia Building (1930) and Occidental Petroleum (1962) buildings are of the latter two designs.

Easement Acquired from Southern Pacific to Cross Railroad (c. 1923)

On September 14, 1923, engineer Erskine Edward “E. E.” Mix (1893-1952) wrote to the Los Angeles City Council on behalf of Cheviot Hills‘ developer Frans Nelson & Sons for the legal right to cross Southern Pacific’s railroad tracks dividing Cheviot Hills and The Palms. Frans Nelson & Sons wanted to connect its new residential to Washington Boulevard (the oldest and main road in the district) via Motor Avenue. In 1923, Motor Avenue ran only up to Irene Street, but people already crossed the railroad tracks to Winship’s Vista del Mar and the nearby farms. Mr. Mix noted that Ole Hanson was developing a neighborhood further north: Monte-Mar Vista while adding that Frans Nelson & Sons had plans to develop Winship’s Vista Del Mar parcel.

The undersigned petitions you to acquire an easement for highway purposes over the Southern Pacific Railroad Right of Way at the intersection with Motor Avenue in The Palms. This easement has now been in use for 25 years or more, but is not a deeded right of way to the public. This crossing is the only one existing in that area for one half a mile in an easterly direction and a mile in a westerly direction and represents the only feasible method of getting into the area lying north of the above mentioned railroad right of way.

(Los Angeles City Council Minutes, September 14, 1923.)

I am at present developing 127 acres lying just north of Hughes Avenue to be known as Tract 7264 and upon which the City Planning Commission has acted and recommended that Motor Avenue be continued through the subdivision, being 80 feet in width. I would be pleased to have you refer this matter to them for recommendation.

In conjunction with the above I have also plans for the development of Winship’s Vista Del Mar subdivision, also bordering Motor Avenue, in which a deeded width of 80 feet is offered. Motor Avenue continued still further north through a subdivision being placed on the market by Mr. Ole Hanson will give a through connection from the National Boulevard to Pico Boulevard and as the topography at the crossing of the Southern Pacific Right of Way allows for sufficient head to develop same as an under crossing, the element of danger may be removed at any time that traffic may become heavy enough to warrant same. At the present time, the Pacific Electric operates this line for occasional freight trains only.

E. E. Mix mistook a couple of facts. First, Hughes Avenue had been renamed Manning by 1923, so Mix was wrong to call it “Hughes Avenue.” Second, the railway carried passengers as well as freight until 1953 (as shown lower down on this page). (Indeed, in 1934 the City rebuffed the railroad’s request to cease the passenger service.) The City granted the developer’s request and obtained an 80-foot-wide easement, which it abandoned when the “under crossing” Mr. Mix predicted came to pass in the 1930s. (June 19, 1933, City Council Minutes.) Ultimately, that undercrossing, and the road to it, involved building a parallel Motor Avenue along a gully already passing beneath the tracks and buying the necessary land – mostly from Winship’s Vista del Mar – to get to it.

Vista del Mar Land Sold for Opening & Widening Motor Avenue (1932)

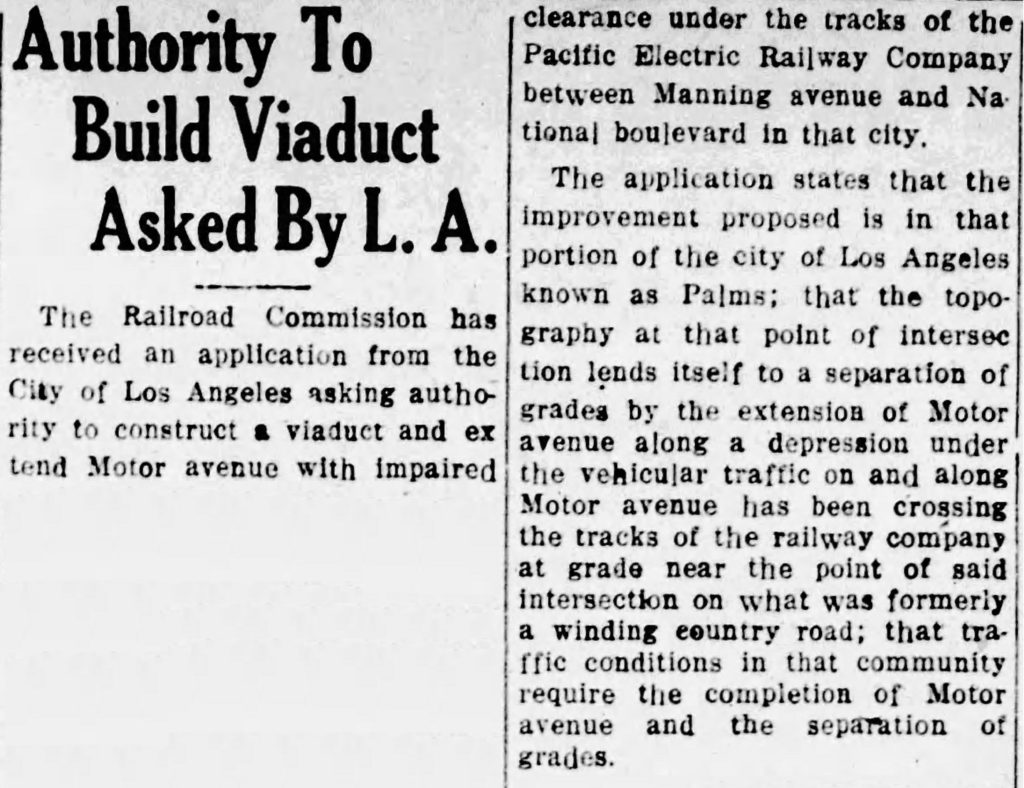

On August 16, 1928, the Los Angeles City Council passed an “ordinance of intention” to build a new Motor Avenue crossing beneath the railroad tracks along an existing gully.

An ordinance declaring the intention of the Council of the City of Los Angeles to order the laying out and widening of Motor Avenue from Manning Avenue to a point approximately six hundred (600) feet southwesterly therefrom, also the laying out an opening of a new street to be known as Motor Avenue from said point approximately six hundred (600) feet southwesterly of Manning Avenue to Motor Avenue at Irene Street; also the laying out and widening of Motor Avenue adjacent to the northeasterly line thereof from Irene Street to a point approximately One Hundred Forty-two (142) feet northwesterly of National Boulevard, together with the taking of additional land for public street purposes at the intersection of the northwesterly line of National Boulevard with the southwesterly line of Motor Avenue, and at the intersection of the northwesterly line of National Boulevard with the northeasterly line of Motor Avenue, in the City of Los Angeles, County of Los Angeles, State of California.

(Los Angeles City Council Minutes, August 16, 1928.)

The proposal was met with protests from owners of over a quarter of the 287 acres in Palms, Cheviot Hills, and Monte Mar Vista who were subject to the $300,000 assessment. Those protests are recorded in its October 17, 1928, Minutes, including in part:

- “I have a lot which I purchased in Nov. 15, 1923 paying 7% interest rates and for street lighting and it has become a great burden for a widow with a very small income to carry. I was told it would be a quick turn over when I [bought]. I am very much discouraged after holding it all this time.” (Jennie E. Phillip.)

- “Motor Ave never will be a throughfare as it begins at Washington Blvd and ends at National Blvd. except as it diverges 1 block beyond to run up into Cheviot hills and it will be many years before traffic thereon will require a wider street. It is not even a business street as more than 1/2 the buildings thereon are private residences … .” (H. E. Thomas.)

- “This district is very thinly populated and it appears to me that there is no necessity nor demand for this work being carried through at this time.” (Howard E. McGee.)

- “Less than a year ago we had a very heavy assessment for Boulevards and storm sewers. If it is necessary to do this street work the whole county should pay for it out of the General Fund as the whole county will surely get more benefit than the poor residence district where Motor Avenue is located.” (Mrs. H. E. Kennedy.)

- “I believe Robertson and National serve all purposes.” (H. J. Hunt.)

- “With slack demand for lots in this Subdivision and taxes and special assessments mounting in cost it is becoming a serious drain on the property owner.” (Willis Maple.)

- “[Too] many of us small lot owners are already [losing] our property by virtue of unnecessary assessments to warrant us any longer keeping quiet. Should this work be done it will doubtless mean my [losing] the lot, as I am in no position to secure the money to pay for it. Increases [in] taxes there and other increased assessments are driving hundreds of well to do widows to abandon their holdings and they in turn are discouraging women as a class from such investments. [T]hat is one reason for real estate depression in Los Angeles.” (Mrs. Bettie E. Smith Hughes and W. Thomas Smith.)

History tells us that early buyers in Cheviot Hills and Monte Mar Vista fell victim to the boom-and-bust real estate market. The housing market was booming in 1923 when the Cheviot Hills and Monte-Mar Vista tracts went on the market. A grand opening newspaper advertisement for Cheviot Hills blasted in bold, capital letters, “PROFITS ARE INEVITABLE.” (L. A. Evening Express, Nov. 10, 1923.) Within three years, the housing market went bust. “The famous stock market bubble of 1925–1929 has been closely analyzed. Less well known, and far less well documented, is the nationwide real estate bubble that began around 1921 and deflated around 1926.” (Harvard Business School, Baker Library, Historical Collections, The Forgotten Real Estate Boom of the 1920s.)

The flagging housing market is likely why the Merchants National Trust and Savings Bank (predecessor to Bank of America) controlled the Monte-Mar Vista development in 1928 and – alongside small lot owners and widows – wrote the City Council that it “hereby protests.” The Rancho and Hillcrest golf clubs also protested: “The improvement is unnecessary, unwarranted at this time, and the cost to us will be out of proportion to the benefit.” Each protest was individually voted on and rejected. And, with fewer than half the owners protesting, the project – and assessment – went forward.

As of December 14, 1931, land for a parallel Motor Avenue had been acquired and the roadway widened – but the viaduct had not been built and the road was not yet paved with concrete.

WHEREAS, Motor Avenue between Manning Avenue and National Boulevard has recently been widened at a cost of $300,957.28; and

(Los Angeles City Council Minutes, December 14, 1931.)

WHEREAS, the entire cost of widening was borne by an assessment district with no aid from public funds; and

WHEREAS, the physical improvements now ordered by the City Council, exclusive of the proposed grade separation structure, are estimated by the City Engineer to cost $39,450.00;

NOW, THEREFORE, BE IT RESOLVED that the City Engineer and Board of Public Works be

instructed to invite bids for said project and advise the Public Works Committee direct of the

exact amount necessary to finance same ….

On January 7, 1932, the City Council authorized advertising for bids for paving, but the viaduct was still unfunded.

Referring to resolution presented by Councilman Coe, relative to an appropriation of $39,450.00 to construct the physical improvements on Motor Avenue between Manning Avenue and National Boulevard, exclusive of the proposed grade separation structure which is to be located at the Intersection of Motor Avenue and the Pacific Electric Air Line:

(Los Angeles City Council Minutes, Jan. 7, 1932.)

We recommend that the Board of Public Works be instructed to advertise for bids

for said improvements; said improvements to be in accordance with the list of the work required prepared by the City Engineer and attached hereto – the pavement to be 6″ cement concrete. ….

On February 19, 1932, the Los Angeles Parks Department’s Forestry Division approved removing “29 large existing Pepper and Eucalyptus trees” for the opening and paving of Motor Avenue. (Los Angeles City Council Minutes, Jan. 7, 1932.) And into 1933, the City was still working to get permission (from the State) and funding (from the County) to build a viaduct over new Motor Avenue.

As of June 15, 1933, the City was asking the County for $5,500 “to provide for the construction of a grade separation at Motor avenue and the Pacific Electric Airline tracks in Palms, part of the projected opening and widening of Motor Avenue from the tracks to Manning avenue in Cheviot Hills.” (Venice Evening Vanguard, June 15, 1933.) By July 28, 1933, the paper reported grading was under way, “and with the installation of the viaduct, paving should be complete within the course of two or three months.” (Venice Evening Vanguard, July 28, 1933.) That viaduct, pictured below, remained until the freeway was built thirty years later.

Freeway takes southern swath

In 1955, the Olympic Freeway (later to be the Santa Monica Freeway) was proposed across the northwest corner of Winship’s Vista del Mar.

Vista Del Mar Child Care Service objected.

Superior Court Judge Stanley Mosk, who said he was appearing before the Commission as president of the Vista Del Mar Child Care Service orphanage in West Los Angeles, contended there were “more direct routes (other than the recommended one) that would do less damage.”

(L. A. Times, Sept. 30, 1955, “Freeway Will Ruin Homes, Board Told”.)

The orphanage, he explained, would suffer the loss of four of its 21 acres if the route is adopted. He said an alternate route would take less acreage but would eliminate three buildings, including a chapel. In any case, the freeway would disrupt the lives of the 200 children the orphanage cares for,” he said.

In 1956, the West Los Angeles Independent Newspaper reported that the alternate route would be accepted.

At the hearing held by the Commission on September 29, 1955, representatives of the Vista Del Mar Childcare Service appeared and, while approving Santa Monica as the “westerly terminus” for the proposed freeway, objected to the location as then proposed because it would require purchase by the state of some four acres of the 21 acres comprising the Child Care Service site. While the area to be acquired for the freeway is at present undeveloped property, it was explained by spokesmen for the childcare service that their plans for expansion included the erection of two buildings at this location. Adoption of some alternate or modified route to the South was urged upon the Commission.

(W. L. A. Independent, Nov. 18, 1956.)

A restudy of the proposed line as it affects the Vista Del Mar Child Care Service was made and the proposed changes, as now recommended by the State Highway Engineer, were explained at the public meeting conducted by Assistant State Highway Engineer E. T. Telford in the auditorium of the Vista Del Mar Child Care Service on April 11, 1956. This reconsideration has resulted in a revision of the line southerly, which will now only require purchase of approximately 1.29 acres of the 21 acres of the property of the Child Care Service. The revised plan includes a new access road to the property from Manning Avenue. Fortunately, none of the buildings of the Vista Del Mar Child Care Service will have to be moved. However, it is recognized that the freeway will come within rather close proximity to the synagogue, a building of frame and stucco construction.

Shifting the freeway south by using the former Exposition Boulevard and the Southern Pacific right-of-way lessened the impact on Vista Del Mar to the point where it no longer objected. Vista Del Mar’s alternative was a “route that would cross east of Bagley [which] would avoid all public buildings and would cut through an older, less expensive residential area.” (W. L. A. Independent, April 19, 1956.) So the move also kept the freeway from displacing houses in new and affluent residential subdivisions: Cheviot Knolls and California Country Club Estates. A Short History of Vista Del Mar Child and Family Services summarizes the impact on its campus: ”Despite protests the freeway finally went through in 1962, requiring the demolition of Vista’s original synagogue and other structures. A new synagogue was built by 1965, with services being held in the gym until it was completed. “

As of 2023, the “severed” southwest piece of Winship’s Vista del Mar – between old Motor Avenue and new – is occupied by Chabad of Cheviot Hills. On about six-tenths of an acre at 3185 Motor Avenue, it is the only other occupant of Winship’s Vista del Mar, which now sits on about 16 of its original acres.

Images from the past

Vista del Mar stands in for the fictional “Bay Area Child Care Service and Orphans Home” in 1958’s The Gift of Love movie.