Monte-Mar Vista

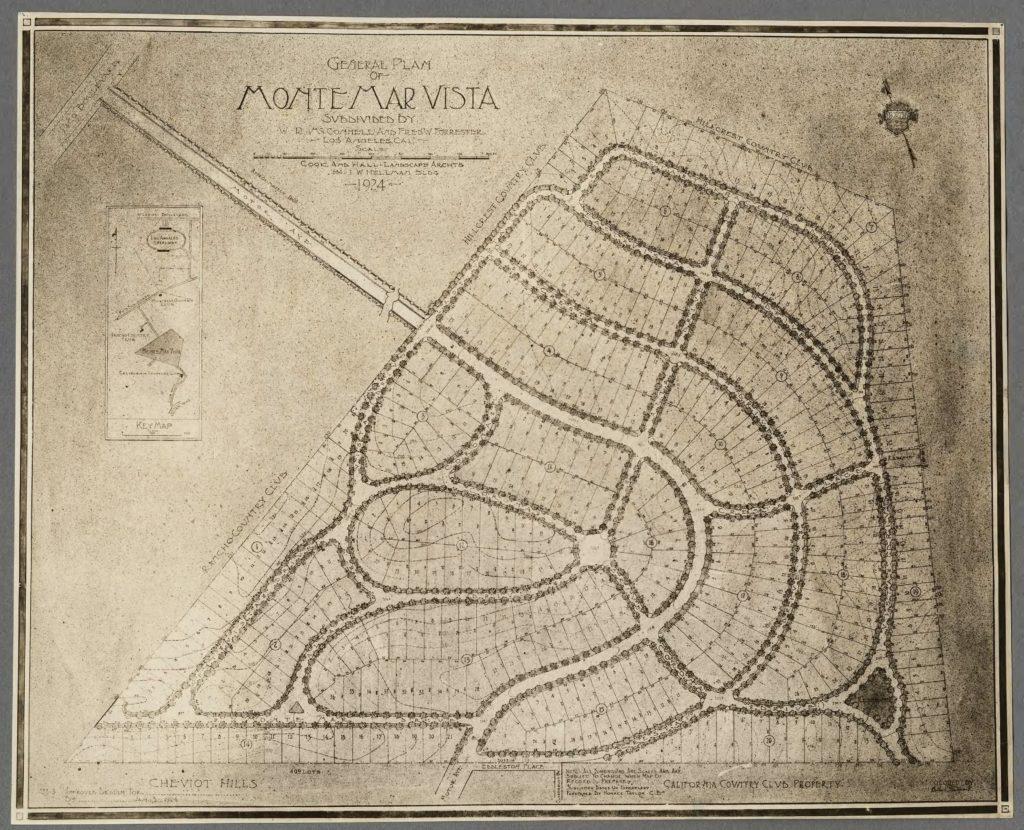

On June 13, 1924, Tract 5713 was registered with the City of Los Angeles, which had annexed the area from the County a year before. The City Council had approved the tract on June 10, 1924. The 409-lot Monte-Mar Vista (Mountain Sea View) tract opened for sale in April 1925. It was notable for concrete streets and underground utilities. Restrictive covenants in deeds to the lots limited the area to expensive, single-family homes. Initially, homes had to cost at least $12,000 to build. During the Great Depression, with about a quarter of the lots still unsold, that was lowered to $4000. That change accounts for the predominance of larger homes on the earlier-sold lots primarily east of Motor Avenue. Cheviot Hills’ deeds required houses constructed on the lots to cost at least $5000. Both tracts’ deeds limited occupancy to whites – except for servants.

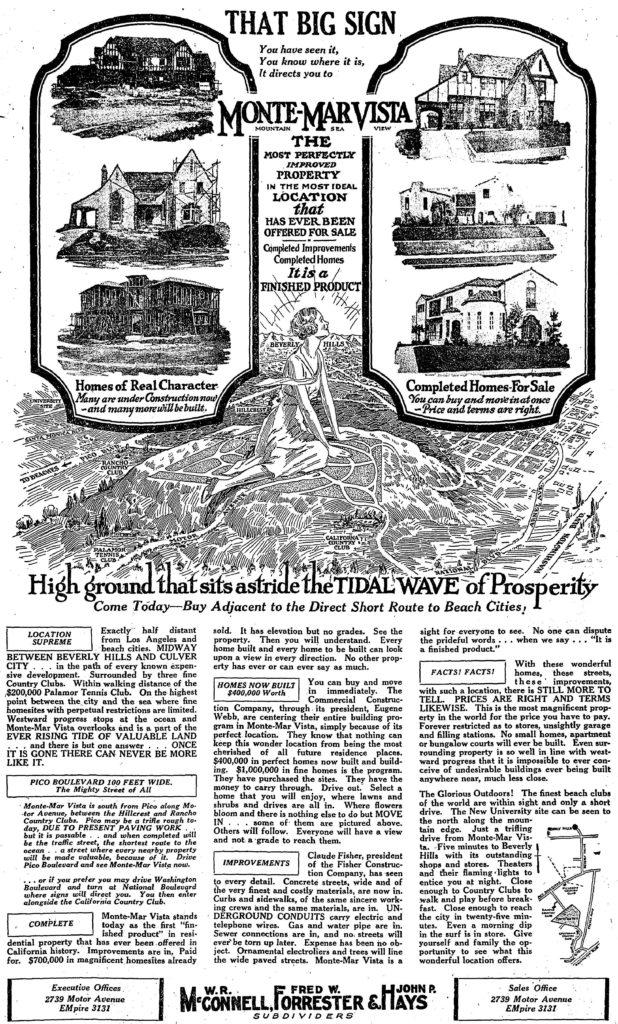

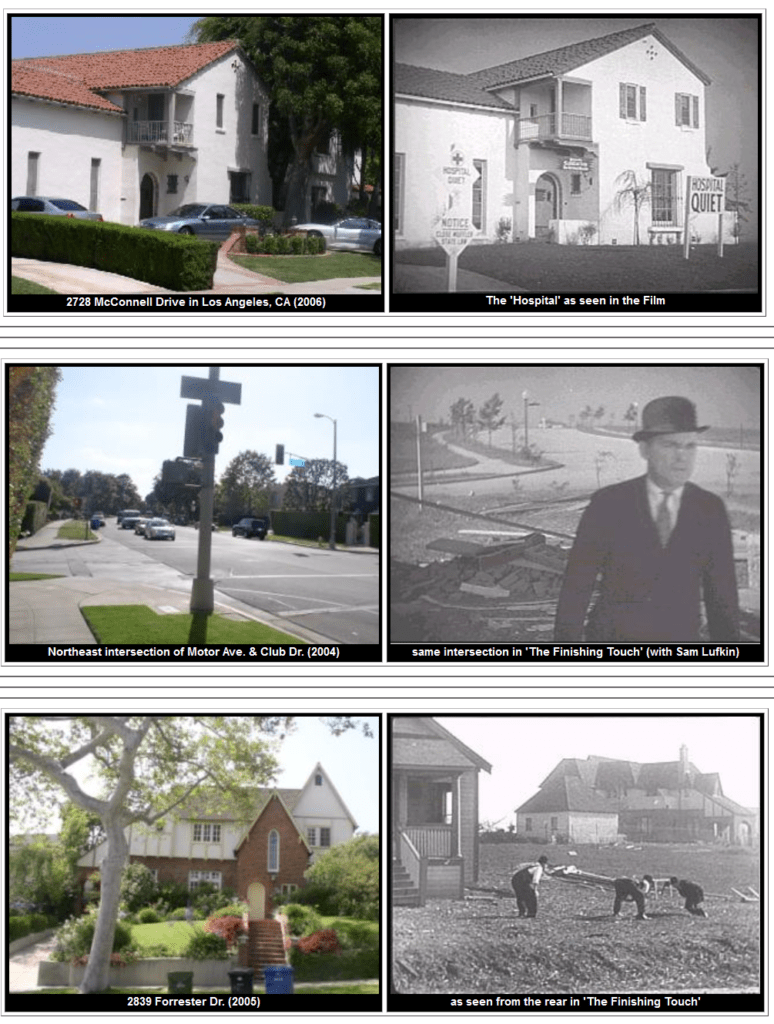

McConnell, Forrester & Hayes of Beverly Hills were the initial developers and agents. Ole Hanson (1874-1940) (who is better known as the Mayor of Seattle (1918-1919) and for founding San Clemente (1925)), was also associated with the development – but when is uncertain, since the story was told decades later by a grandson of Cheviot Hills developer, Frans Nelson (who said the elder Nelson and Hanson were friends). The McConnell, Forrester & Hayes firm exited Monte-Mar Vista in early 1928, if not sooner, when sales were taken over by noted developer Frank Meline Company. (The latter apparently removed the hyphen from Monte-Mar in their advertising.) During the Great Depression, Bank of America’s “Capital Company” (which may have taken the land in foreclosure) was in charge.

McConnell, Forrester & Hayes – developers

Fred Warren Forrester (1878-1941), whose own “Terrace View” home (shown below) was one of the great houses in the neighborhood, helmed the Angeles Mesa Land Company when it developed the Angeles Mesa subdivision. In 1913, he hyped the inherent value of view lots on Angeles Mesa’s high land, as he would a decade later for Monte-Mar Vista. According to a report prepared by the County of Los Angeles, Forrester’s father, Edward Arnold Forrester (1832-1917), was “one of the pioneer realty operators of Los Angeles” and also a county supervisor. E. A., Fred, and Arthur Walter Forrester ran “a general real estate and subdivision business under the name of E. A. Forrester & Sons part of the family operation,” which included the Westlake tract including Westlake Park, Porter Ranch, Simi Valley, an area around Calabasas, and the 1907 Forrester Building which remains at 640 South Broadway in Los Angeles.

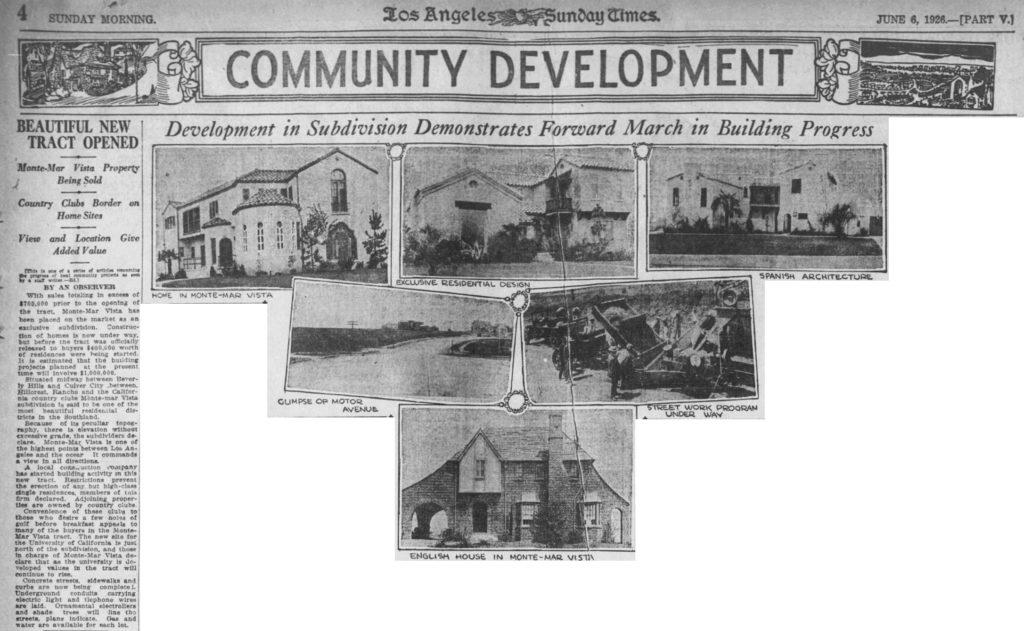

The Los Angeles Times reported on the nascent residential development:

This property, being subdivided by McConnell, Forrester & Hayes, Beverly Hills realty firm, is bounded on the northeast by the Hillcrest Country Club, on the west by the Rancho Country Club and on the south by the California Country Club. The fourth side is bounded by a high-class residential district [the Cheviot Hills and Country Club Highlands subdivisions.] With these advantages the subdividers have provided suitable restrictions for the construction of homes, the minimum cost being $12,000 [around $220,000 in 2023 dollars].

L. A. Times, May 17, 1925.

FOR SALE!

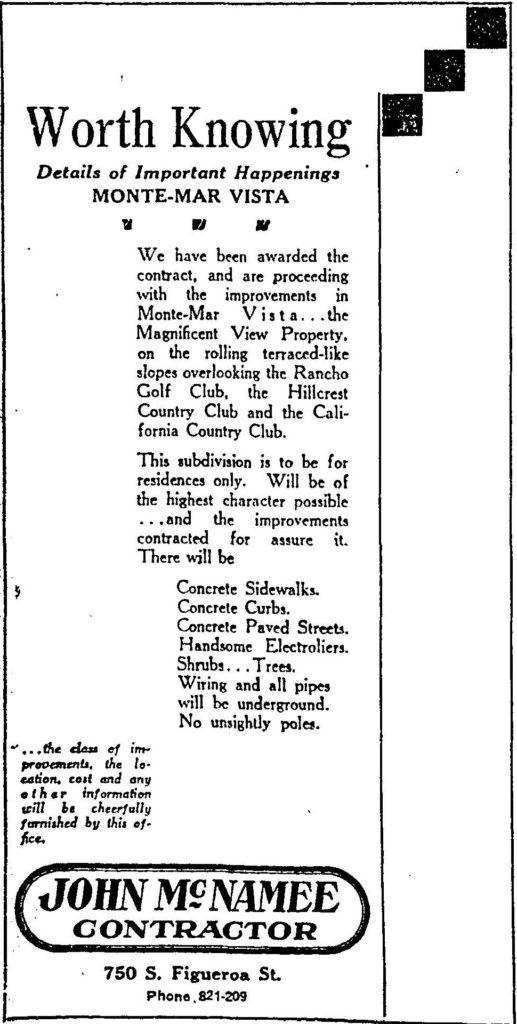

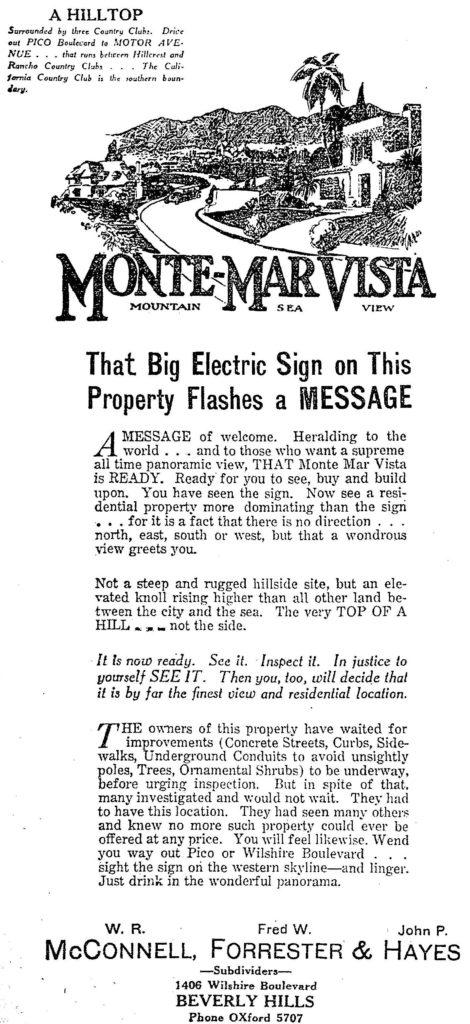

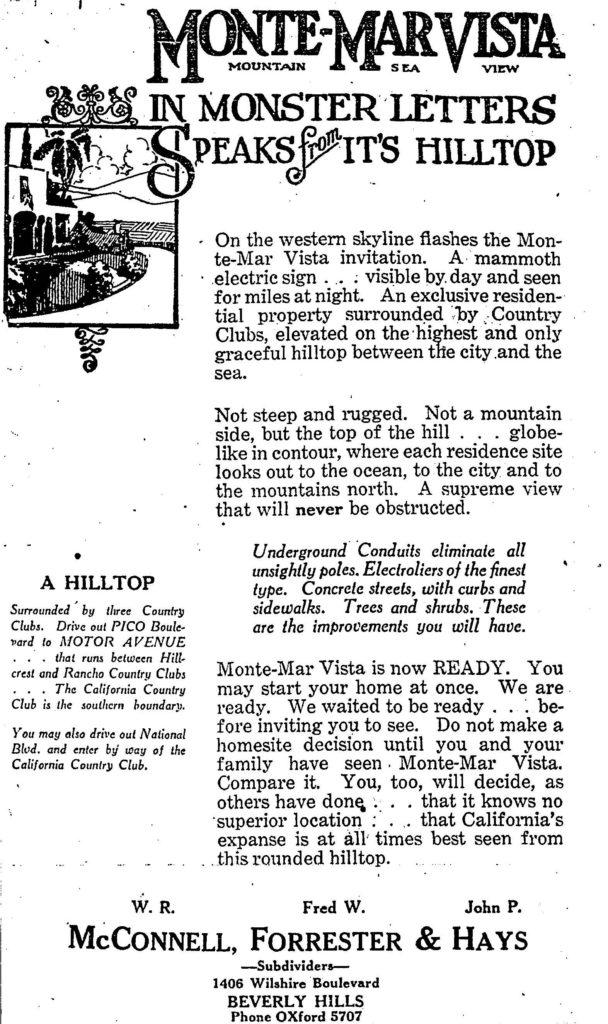

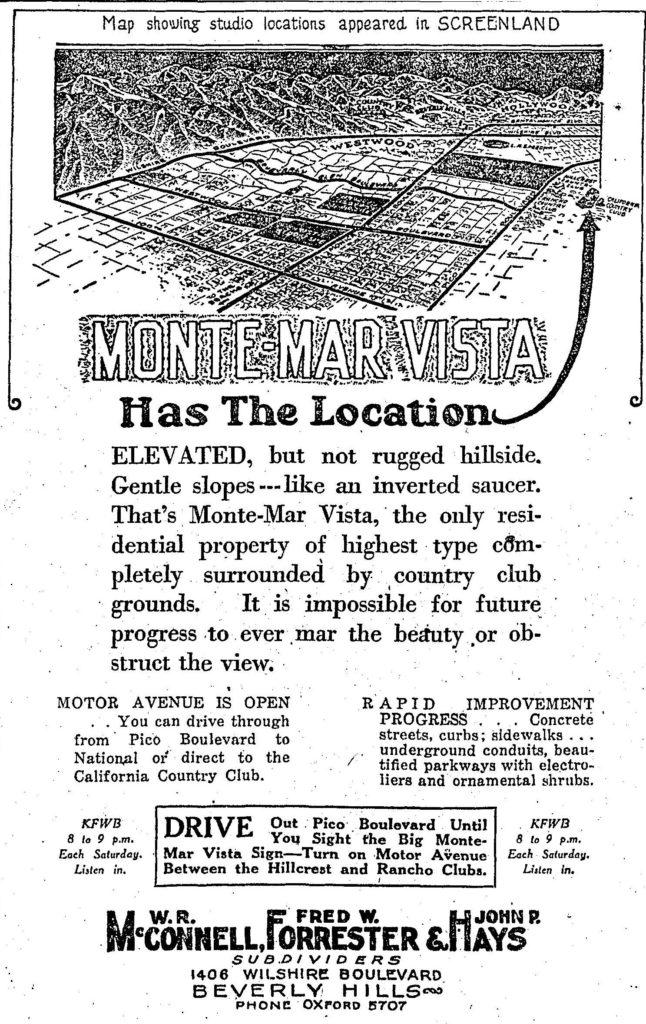

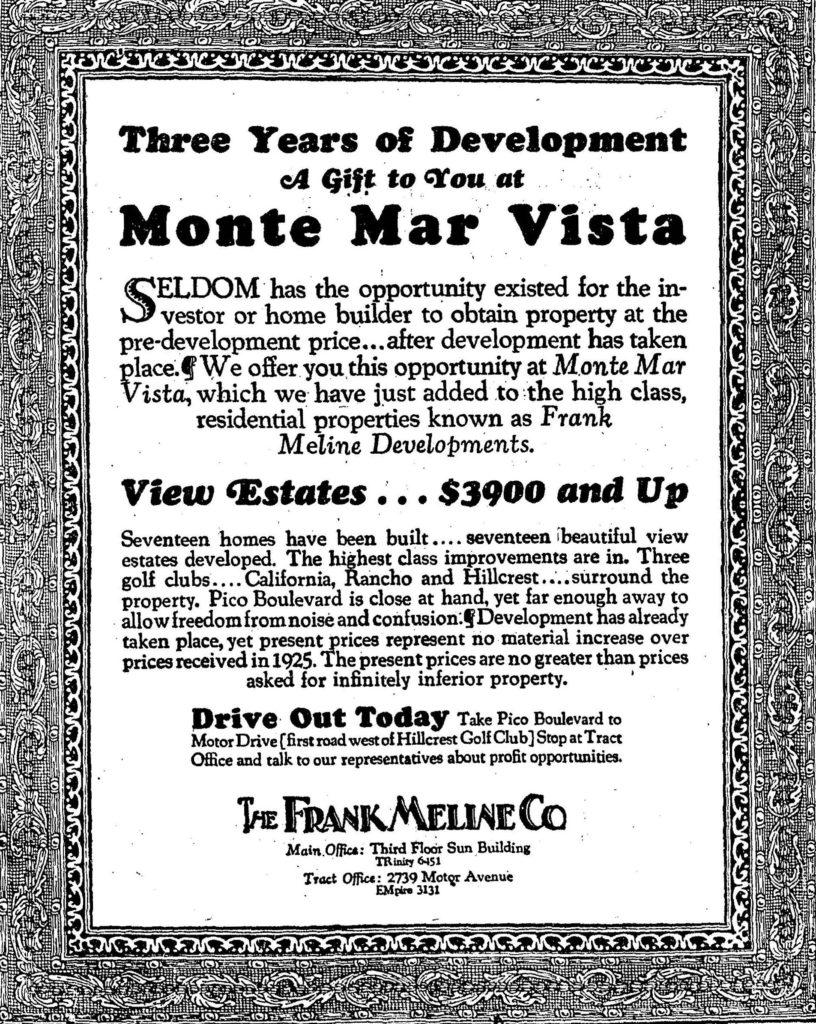

Developers advertised proximity to Pico Boulevard: “close at hand, yet far enough to allow freedom from the noise and confusion.” With “concrete winding boulevards” and “not a pole in sight – utilities are underground,” homes on streets such as McConnell and Forrester were “priced for quick sale at $3900 and up.”

Promotion included illuminated Monte-Mar Vista letters (illuminated at night) of the sort erected in 1923 to ballyhoo the Hollywoodland development as well as for the Cheviot Hills tract next-door. The developers also sponsored a Saturday night KFWB radio show through Summer 1925, which sometimes featured the “Monte Mar Vista Orchestra” or the “Monte Mar Vista Syncopators.

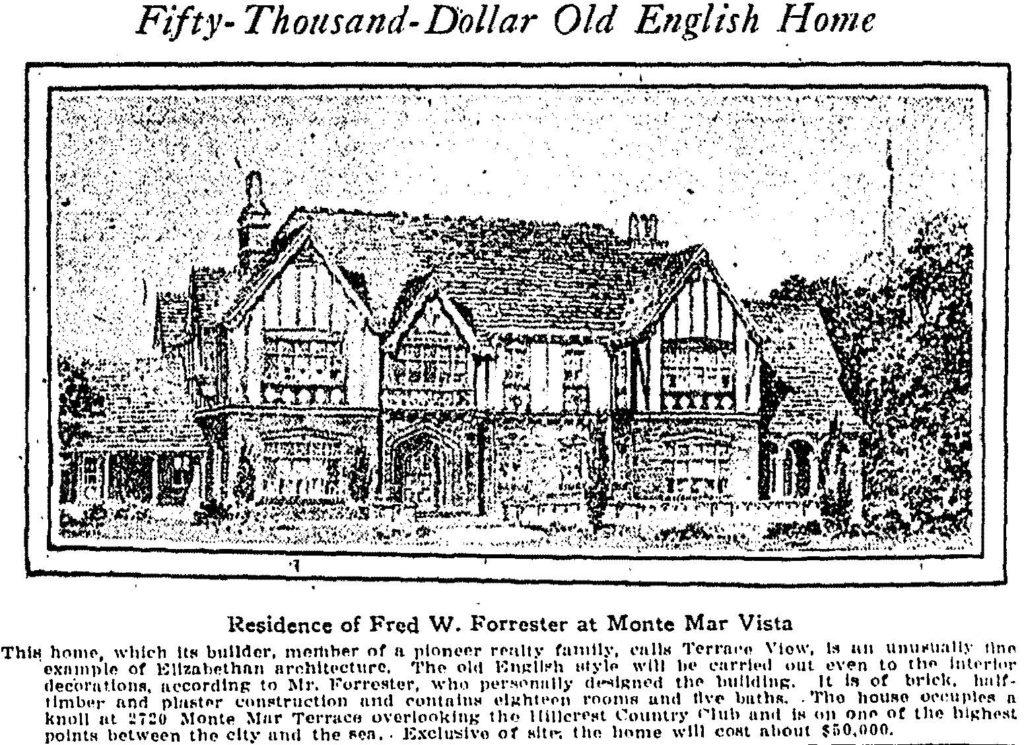

Forrester’s “Terrace View” home, at 2720 Monte Mar Terrace, set a standard noted by the Los Angeles Department of Planning:

Given the affluence of the area’s residents who had the financial means to retain top architects to design their homes, known architects who designed properties in the area during the 1920s and 1930s include John L. DeLario, Roland E. Coates, and Eugene R. Ward. Developer Forrester designed his own house in the district in an elaborate Tudor Revival style. Despite the moderate to large lots, some of the houses are so expansive that they extend across several parcels.

“SurveyLA” 2011.

Advertising in the Los Angeles Times (and the KFWB radio show sponsorship) apparently stopped between Summer 1925 and mid-1926. Then, on May 30, 1926, the Times profiled the residence of developer Fred W. Forrester: “Fifty-Thousand-Dollar Old English Home.” The amount may have been exagerrated: the building permit shows $41,000. The permit also shows that Commercial Construction Company was to build Forrester’s house. In January, Commercial Construction Company’s president, Eugene Webb, Jr. (1891-1972), had announced he would build his own “100 per cent fire and earthquake-proof” steel home in Monte-Mar Vista. That is one instance of Commercial Construction Company’s connection with Monte Mar Vista. The following week, on June 6, 1926, the Times carried another Monte-Mar Vista advertisement and article. It noted homes built by Commercial Construction Company and roads built by Fisher Construction Company.

Contrary to the advertisements, Monte-Mar Vista was not completely surrounded by a “high-class residential district” and country clubs. Instead, immediately to the east was the Minorini family farm (formerly the Arnaz Ranch) owned by the Marblehead Land Company. (Marblehead was owned by the Rindge family, which also owned Malibu.) As Nathan Masters tells it in “Monte Mar Vista: Luxury Homes With a View (of an Oil Derrick),” in 1927, oil-drilling started there. The city of Los Angles (which had annexed the area only 4 years before) promptly passed an ordinance prohibiting oil-drilling; it was upheld in court in 1931. With the Great Depression on, land-rich/cash-poor Marblehead was bankrupted, and, by 1939, the former Arnaz Ranch was held by investors who would build Beverlywood.

Among the developers associated with the tract, W.R. McConnell and Fred W. Forrester are the only ones to have their names attached to streets – and to a lawsuit, when the advertising manager (John R. Case, Jr.) and sales manager (Brockett) sued them and Bank of America (which held the land in trust) for unpaid commissions. The case reports refer to a March 15, 1927, Amended Declaration of Trust; it is unclear when the trust arrangement began. What is clear is that the original developers were out by February 1928.

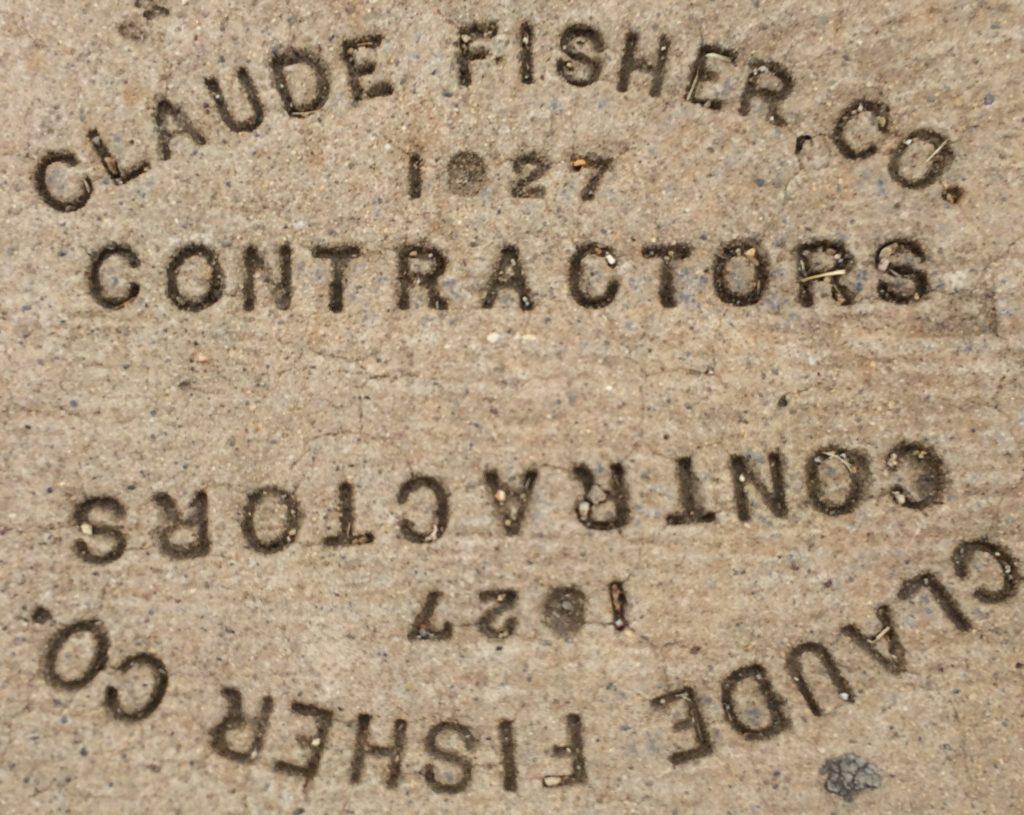

Frank Louis Meline (1875-1944) was an architect and the first sales agent in Bel-Air for developer Alphonzo Bell (1875-1947). Meline subdivided Pacific Palisades’ California Riviera neighborhood, where some streets also bear the Claude Fisher Company stamp seen in Monte-Mar Vista. Meline was a prominent developer who

in 1912 formed his own Los Angeles construction company, which he expanded in 1919 to a full-service real-estate development and sales operation with (by 1924) eighteen branch offices throughout the Los Angeles basin. As a broker, Meline sold half the homes purchased in Beverly Hills before 1930.

Kevin Starr, Material Dreams: Southern California Through the 1920s (Oxford Univ. Press 1990)

On February 12, 1928, the day that Los Angeles Times reported that Frank Meline and Company had taken over Monte Mar Vista, the following advertisement appeared.

A 1931 Los Angeles Times account has Fred Forrester as “exclusive agent for Monte Mar Vista” when he reported several sales. Alfred Gottlieb Theophele “A. T.” Schaber (1893-1962) bought at 2736 Monte Mar Terrace; he owned Schaber’s cafeteria at 620 South Broadway, south of the Forrester Building, with the Palace Theater in between. Another reported sale was a $50,000 home to “capitalist” Claude Fisher (1884-1940), whose Claude Fisher Co. built dams, commercial buildings, and streets – including in Monte-Mar Vista. Earle John “E. J.” Campell of the Blue Bird Laundry bought a ninety-foot corner at McConnell and Cresta (2740 McConnell) for a “ten-room home of the Spanish type.”

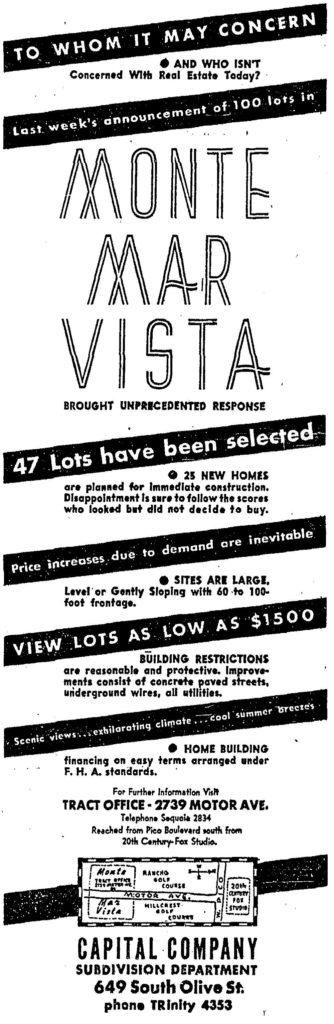

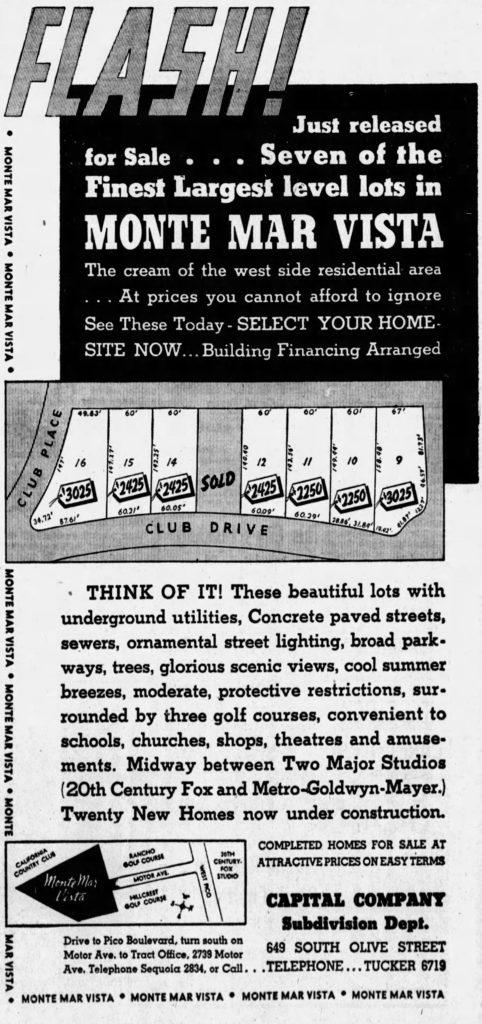

The Great Depression – The Bank is Selling

A new round of advertisements began in 1937 (during the Great Depression) with the Capital Company, a Bank of America subsidiary that apparently handled foreclosed properties. Less expensive homes were allowed – apparently down to $4,000 from the original $12,000. On March 14, 1937, in an article entitled, “Monte Mar Vista Opens Up 100 New Residential Sites,” the Los Angeles Times reported that the Capital Company’s subdivision department, through its “general broker” Harry T. Hudson, would offer 100 homesites.

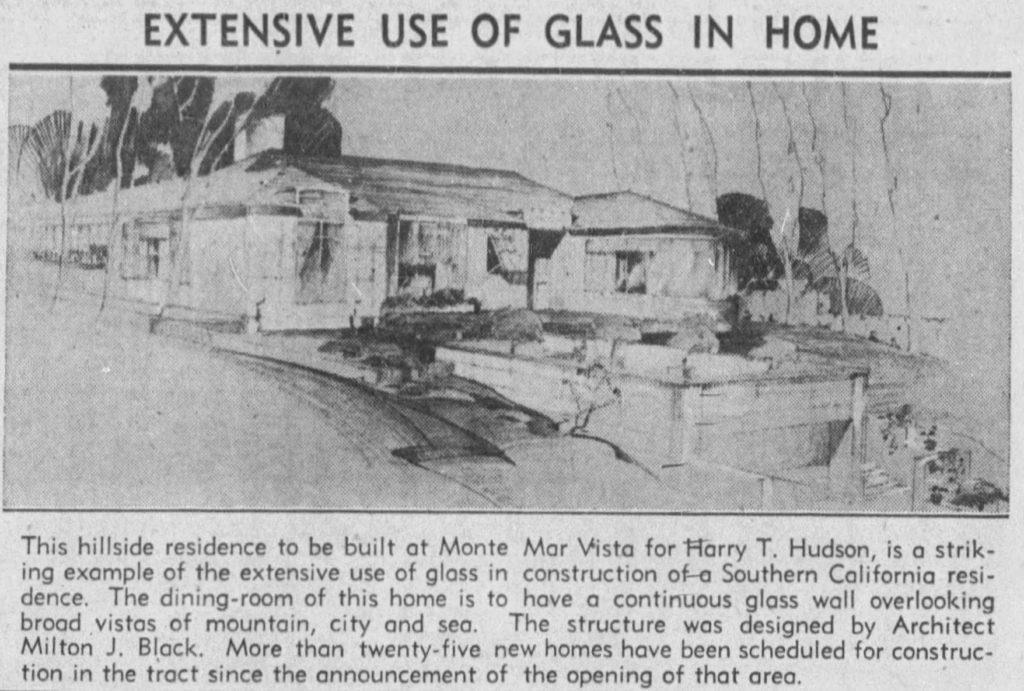

Hudson publicized that he would have a Monte Mar Vista home built for himself, designed by architect Milton J. Black. Mr. Black is today “probably best known for his outstanding Streamline Moderne structures, which include the Mauretania Apartments in Hancock Park [1934] and this lovely Los Feliz specimen that’s just hit the market” (Curbed LA) and for the programmatic Tail o’ the Pup hot dog stand (1946).

Protective building restrictions have been modified so that in certain sections one-story modern homes of the rambling farmhouse or early California types may be built, according to the announcement. The wide frontage of 60 to 125 feet enables prospective builders to plan homes which require wide proportions, it was explained.

Racist Restrictions and Redlining

In 1917, the United States Supreme Court held unanimously that a Louisville, Kentucky, city ordinance prohibiting the sale of real property to blacks in white-majority neighborhoods violated the Fourteenth Amendment’s protections for freedom of contract. (Buchanan v. Warley (1917) 245 U.S. 60.) In response, private developers exercised their “freedom of contract” to place restrictive covenants in titles to property – restricting residence to whites. In 1919, the California Supreme Court began enforcing such restrictive covenants. (Los Angeles Inv. Co. v. Gary (1919) 181 Cal. 680.) In the 1920s, developers of the Monte-Mar Vista and Cheviot Hills tracts inserted such restrictive covenants in the titles to the property they sold. So did Janss Investment Company, developer of the nearby Westwood tract – restrictions the California Supreme Court would uphold.

In 1922, a White man (James J. Henry Walden) bought property in the Westwood tract to transfer it to a Black family (the Wallings). Developer Janss Investment Company successfully sued to stop the transfer by enforcing the restrictive covenant it had placed on its subdivision: “No part of said real property shall ever be leased, rented, sold or conveyed to any person who is not of the white or Caucasian race, nor be used or by any person who is not of the white or the Caucasian race whether grantee hereunder or any other person.” The California Supreme Court upheld Janss’ restriction and stopped the transfer to the black family, saying it was obliged to following its 1919 decision. (Janss Inv. Co. v. Walden (1925) 196 Cal. 753, 754.) Pioneering African American, Harvard Law (1908) civil rights lawyer Willis O. Tyler (1880-1949) represented Walden and the Wallings. Harvard Law’s (1922) Elmo H. Conley (1896-1957) of Los Angeles’ own Gibson, Dunn & Crutcher represented Janss.

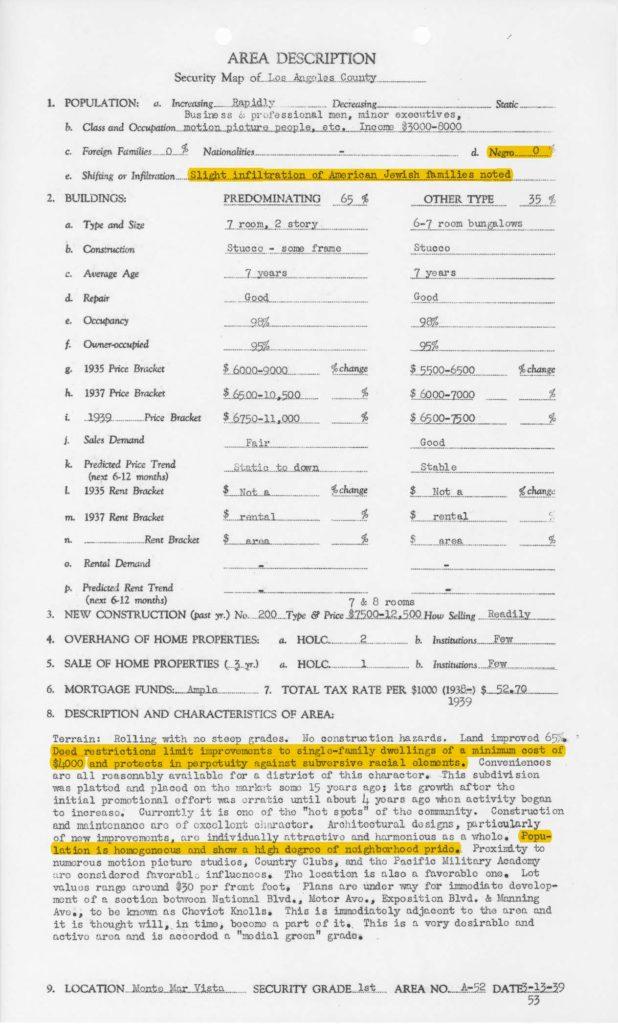

Complementing the restrictive covenants (even if discriminatory zoning laws were nominally off limits), the federal government found other ways to aid and abet housing discrimination. The National Housing Act of 1934 created the Federal Housing Administration (FHA) to increase the market for single-family homes. The FHA’s strict lending standards, contained in the FHA Underwriting Handbook, governed whether mortgages were eligible for National Housing Act insurance.

The FHA Handbook restricted the kinds of properties for which it would approve mortgages based on (among other factors) racial and ethnic composition. It favored restrictions including “Prohibition of the occupancy of properties except by the race for which they are intended” (1938 FHA Underwriting Manual, sec. 980 (3)(g)).

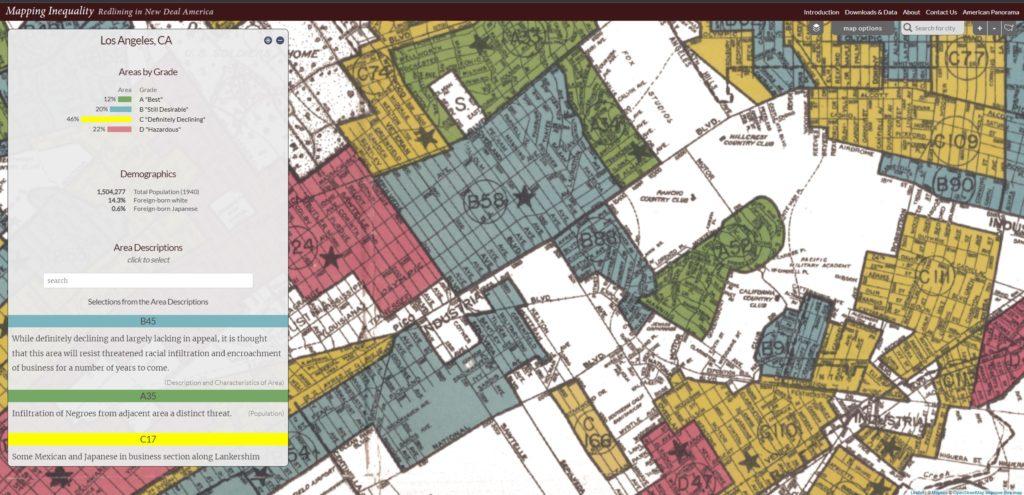

Around the same time, the federal government established the Home Owners’ Loan Corporation (HOLC) for refinancing mortgages that were in default in order to avoid foreclosures. HOLC created maps and area descriptions along the same lines as the FHA Manual. Maps were shaded from green to red, i.e., from most to least desirable. Those maps are the basis for the term “redlining.”

The 1930s Capital Company (Bank of America) advertisements shown above say “BUILDING RESTRICTIONS are reasonable and protective,” “HOME BUILDING financing on easy terms arranged under F. H. A. standards,” and “F. H. A. Approved Properties.” Those restrictions, standards, and approval meant that the federal government was helping ensure racial segregation.

The Monte-Mar Vista tract rated highest with HOLC and met the FHA standards for, among other reasons, deed restrictions limiting improvements to single-family dwellings of a minimum $4000 and “protect[ing] in perpetuity against subversive racial elements.”Deed restrictions limit improvements to single-family dwellings of a minimum $4000 and protects in perpetuity against subversive racial elements.

The maps also portray the area’s development: “This subdivision was platted and placed on the market some 15 years ago; its growth after the initial promotional effort was erratic until about 4 years ago when activity began to increase. Currently, it is one of the ‘hot spots’ of the community.” “Plans are under way for immediate development of . . . Cheviot Knolls.”

With 1948‘s Supreme Court decision in Shelley v. Kraemer (1948) 334 U.S. 1, courts could no longer enforce restrictive covenants. But realtors still discriminated. So, in 1963, California passed the Rumford Fair Housing Act to help end racial discrimination by property owners and landlords who refused to rent or sell their property to “colored” people. Soon after, in November 1964, 65% of Californians voting passed Proposition 14, amending the state constitution to nullify the Rumford Act and legalizing private racial discrimination. In 1966, the California Supreme Court declared Proposition 14 unconstitutional under the equal protection clause of the United States Constitution (Fourteenth Amendment). The U.S. Supreme Court affirmed that decision in 1967 in Reitman v. Mulkey (1967) 387 U.S. 369.