José de Arnaz (1820-1895) was a traveler, merchant, medic, county supervisor, judge, supervisor of schools, druggist, banker, miller, tanner, farmer, vintner, and cattle rancher. At the age of sixteen, Spanish-born José shipped as a cabin boy to Havana, Cuba, where he stayed for three years, working as a clerk by day and studying medicine at night. He came west in 1840 as a “supercargo,” the person responsible for overseeing and selling a merchant ship’s cargo. In that capacity, he travelled from ranch to mission, visiting customers from San Diego to San Francisco. He settled in Ventura and Los Angeles.

The facts on this page come from several sources from during and after Don José’s lifetime. Contemporaneous newspapers reported on Arnaz occasionally. (In April 1850, Washington D.C.’s The Republic called him “Joseph Arnaz” when reporting his putative ownership of the Ex-Mission San Buenaventura.) In 1872, Hubert Howe Bancroft, who was compiling a history of California, sent one of his staff (Thomas Savage) to get Don José’s memories of his life and times, producing Recuerdos (memories) translated and reproduced here. (Arnaz’ Recuerdos tell of trade, crime, and social life and customs in California before and after the Mexican-American War (1846-1848).) In 1883, Jesse D. Mason published his History of Santa Barbara County, California, with illustrations and biographical sketches of its prominent men and pioneers; it includes Arnaz, of course, and an extensive discussion of how (or whether) he got valid ownership of Ex-Mission San Buenaventura. Other facts are from lawsuits concerning Arnaz’ deceased wife’s property; the court opinions (from 1873 and 1876) generally recite facts alleged by her heirs without evaluating their accuracy.

Historian Luther A. Ingersoll gave Don José some attention in his 1908 California history book, while Sol N. Sheridan featured him prominently in his 1926 History of Ventura County. Neither historian closely cited his sources; the latter credits his brother, Mr. E. M. Sheridan, Curator of the Pioneer Museum. (Sol N. Sheridan, History of Ventura County, California (S. J. Clarke Publishing Co., 1926), foreword.)

A 1939 newspaper article, “Romance of a Rancho,” recalled Arnaz’ life story on the occasion of the upcoming demolition of his Los Angeles ranch. The unidentified author of that colorful history had the help of one of Don José’s daughters, Prexcedes Arnaz de Lavigne, “whose memory and whose research into old archives provided many facts.”

In 1965, the Ventura County Historical Society republished a translation of part of Recuerdos, and, in 1981, it published his will and a letter an illustrious neighbor, Thomas R. Bard, wrote to his sister describing Arnaz. Their publication is the source for the pictures at the top of this page. This author will do his best and try to link later researchers to original materials so that they can (as he has) build on past works.

Don José is better remembered in Ventura County (until 1873, it was part of Santa Barbara County) than in Los Angeles County. In 1926, historian Sol N. Sheridan wrote:

He is worth a chapter to himself, in any real history of Ventura County. Would you believe that, in that distant day when California was more remote, even, from the world’s cultural centers than the South Pole is today, a resident of San Buenaventura, a man of Spanish blood, would advertise a realty subdivision here in papers of New York? That was Jose de Arnaz; and the subdivision was advertised in Leslie’s Weekly and in the Scientific American in 1846 – almost before the Mexican war had ended.

Sol N. Sheridan, History of Ventura County, California, p. 89.

Ventura Granted/Sold to Arnaz – or not

In his 1883 History of Santa Barbara County, Jesse D. Mason wrote that the Ex-Mission San Buenaventura Rancho was

granted as twelve leagues [just over 86 square miles] to Jose de Arnaz, by Governor Pio Pico, June 8, 1846. Arnaz sold it to M. A. R. Poli in 1850. The claim was confirmed by the United States Land Commissioner for the Southern District of California, May 15, 1855, and finally by a decision of the United States District Court, April 1, 1861. The United States patent was issued in August, 1874, for 48,822.91 acres to the grantees.

J. D. Mason, History of Santa Barbara County, California, with Illustrations and Biographical Sketches of its Prominent Men and Pioneers (Thompson & West, 1883), p. 408.

A quarter century later, historian Luther Ingersoll wrote that his “title was not recognized by the United States government.” (Luther Ingersoll, Ingersoll’s Century History, Santa Monica Bay Cities (1908), p. 32.) Perhaps the title was not recognized due to allegations that the grant was fraudulent. Josefa Arenas swore that her step-son Cayetano Arenas, an Arnaz neighbor in Ventura (Sheridan, p. 98), claimed he forged the deed of the Ex-Mission of San Buenaventura to Don José. He supposedly said he did it in exchange for “Portrero” (pasture) from Arnaz’ buyer, M. A. R. de Poli, who himself depended on good title. Here is what Josefa Arenas swore:

I know, of my own knowledge, that Jose de Arnaz and Narciso Botelo had the Ex-Mission of San Buenaventura leased for several years, and until Colonel Stevenson took possession of the whole Mission establishment, cattle, horses and lands, and everything belonging to said establishment. Colonel Stevenson then leased the whole establishment to a man, the name I do not recollect. I had a step-son by the name of Cayetano Arenas (now deceased), who was acting as Secretary for Governor Pico, when the said Pico was Mexican Governor of California; said Arenas told me repeated times that the grant of the Ex-Mission of San Buenaventura was a fraud; that he (Cayetano Arenas), made the deed and dated it back, and then went to Los Angeles and testified before some court to the genuineness of said deed, for which one Dr. Poli was to give him a deed for the Potrero on which he (Cayetano Arenas) then lived, but which the Dr. Poli failed to do before he died, and then his successor ejected him out of the said Portrero. Said Cayetano Arenas also told me that the deed made to Arnaz, purporting to have been made by Pio Pico, was all in his (Arenas’) handwriting, and dated back to make it appear legal. At the time said title was made the Americans were already in possession of the Country.

Affidavit of Josefa Arenas, December 23, 1872, reported in Jesse D. Mason’s 1883 History of Santa Barbara County.

It is reported that the mission lands were “first rented for $1,630.00 per annum, and then sold to José Arnaz for $12,000, in June, 1846.” (Luther Ingersoll, Ingersoll’s Century History, Santa Monica Bay Cities (1908), p. 32.) The $12,000 purchase price amounts to nearly $473,000 in 2023 dollars.

The Catholic Church also attacked – successfully – Arnaz’ ownership of the San Buenaventura Mission itself – as distinct from the “Ex-Mission,” surrounding lands. And President Lincoln agreed, ordering Arnaz to return the Mission:

After California became a state of the Union, Bishop Joseph Sadoc Alemany petitioned the United States Government to return that part of the Mission holdings comprising the church, clergy residence, cemetery, orchard, and vineyard to the Catholic Church. The request was granted in the form of a Proclamation by President Abraham Lincoln on May 23, 1862.

San Buenaventura Mission website, apparently authored by the Santa Barbara Pastoral Region (SBPR) of the Archdiocese of Los Angeles.

Ventura’s Founder/Subdivider and First Storekeeper

“As early as 1848 Don Jose Arnaz laid out a town site near the Mission, advertised the advantages of the place in the Eastern papers, and offered any one a lot who would make improvements thereon.”

Mason, p. 351.

Sheridan reports that Arnaz advertised lots “in Leslie’s Weekly and in the Scientific American in 1846 – almost before the Mexican war had ended” (Sheridan, p. 89) and in the New York Herald (id., p. 391). Whatever the date, Arnaz is often credited as the founder of Ventura, California. (Its actual name is City of San Buenaventura, for the 48,823-acre Mission San Buenaventura.) Mason puts the date later. But both historians report that Arnaz “established the first store in the county” with Russell Heath (who was also sheriff) and a man named Morris. (Mason, p. 350.) Sheridan does not include Morris, saying that in the late-1840s, Arnaz and Heath

opened the first general merchandise establishment within the limits of what is now Ventura County. It was at about this time that Arnaz laid out the townsite of San Buenaventura; and advertised town lots in a New York newspaper. He was the great avatar of the latter day sub-division promoter. And Arnaz had something worth while to offer. As many a latter day owner of town lots in San Buenaventura will testify.

(Sheridan, p. 197.)

Marriage to Merced Abila & Residence in Ventura

In 1847, Arnaz married Maria Mercedes de Abila (1832–1867). Also known as Merced Abila (with the alternate spellings Avila and Avilla found), she would have been 14 or 15 years old at the time. They lived by the Mission San Buenaventura.

“On the south side of Main Street, beginning at the bank of the river, were the residences of P. Ruiz, Juan Bravo and Jose de Arnaz – the last afterwards the American Hotel, run by the late Volney A. Simpson. The Arnaz pear orchard, afterwards washed away in a flood, extended down into the present bed of the river. Next to the Arnaz home was the Mission orchard wall, running eastward at that point two blocks.”

(Sheridan, p. 98.)

Arnaz was also a great success in the field of agriculture. He planted the first field of wheat and raised the first crop of lima beans in Ventura County. …. Arnaz was also a supervisor from Santa Barbara County, which, at that time, included San Buenaventura. He was also one of the owners of the Santa Ana Water Company.

Ojai History website

John C. Fremont

Arnaz’ Recuerdos describes an early-1847 encounter with Colonel John C. Fremont (1813-1890), who threatened his life during the Mexican-American War: “the only reception Colonel Fremont gave me was to tell me to prepare myself; that I was going to be executed!“. Arnaz and Fremont parted on good terms, although Fremont did not keep his promise to repay Arnaz for the horses, saddles, meat, and cattle Arnaz provided – something Arnaz notes in his Recuerdos and, apparently, in his will (“I declare that I hold a claim against the government of the [United States] if some day justice is practiced for me, what I obtain I leave a third part to the children of my first mate, another to the children of my second mate and the other to my wife [Maria Camarillo] de Arnaz.”)

Sheridan expands on Arnaz’ experience with Colonel Fremont:

Don Jose, a brave man as he was to prove conclusively a little later, apparently saw no reason why he should abandon his home at the coming of the American leader. Moreover, it is likely enough that he knew Fremont – had very probably met him in the days before the American conquest at Monterey. …. Fremont needed horses and pack animals to replace those lost in crossing the San Marcos, and Arnaz supplied him with them. The American commander gave notes for these animals-which Arnaz, by the way, was never able to collect from the American government. The bill, as a matter of fact, has never been paid.

Sheridan, p. 85.

Jonathan D. Stevenson

Arnaz’ 1848 experience with another Mexican-American war commander, Colonel Jonathan D. Stevenson (1800-1894) was worse, as told in Recuerdos:

He, refusing to recognize me, under the pretext that the title had been forced after the return of Pío Pico to the country, that is after the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, using his armed forces, took over the Mission of San Buenaventura and all of the businesses in said establishment …, even divesting me of my Los Angeles orchard and vineyard, which he occupied with his soldiers, who burned the house, appropriating whatever was there. In his exaltation he even took my horse’s saddle, leaving me with my family in poverty, and I have not to this day been able to understand the reason for these violent and arbitrary proceedings, as only I was attacked.

Sheridan’s version of the story is more harrowing than Arnaz’:

Arnaz was destined to have a later experience with American soldiers which was not to end even so well as his meeting with Fremont. Fremont went on south toward Los Angeles-and at Cahuenga Pass received the final surrender of the California forces which made California definitely an American possession. Presently, Stevenson’s Regiment, recruited in the slums of New York City for service in California, reached San Francisco – and a detachment of this force was sent south to hold Santa Barbara. These soldiers of Stevenson, whatever they did elsewhere in the state, do not seem to have conducted themselves in this vicinity in the most exemplary manner possible. A detachment of them, sent out from Santa Barbara, it is not very clear for what purpose, made its appearance at San Buenaventura. The first man they found, too, was Don Jose Arnaz. As the administrator of the temporalities after the departure of the Franciscans, Don Jose had charge of the Mission church and buildings. It is possible that, in those troubled times, the church and the church buildings were unused for certain periods.

Sheridan, pp. 85-86.

They were kept locked, at all events. And there were tales – there have always been such tales – that the Franciscan Fathers had a great store of gold and silver hidden somewhere within the church or the Mission buildings. Don Jose, as the administrator, kept the keys. The ruffians of the Stevenson regiment demanded that he give them the keys that they might make a search for the supposed treasure. And Don Jose, like a brave man, refused to betray his trust. The soldiers, not to be thwarted, took him out into his own pear orchard, selected a flourishing tree there, and threatened to hang him higher than Hamen if he did not give up the keys. Don Jose told them to go ahead. The keys were where they could never find them. And they actually put a rope about his neck, and seemed ready to carry their threat into execution. But they did not. Perhaps wiser counsels prevailed. Perhaps it had all been but a threat, anyway. Perhaps the splendid bravery of the Castilian awed the ruffians in spite of themselves.

At all events, Don Jose de Arnaz was not hanged. He lived to raise a large family, and to become an esteemed citizen amongst the new owners of the land. All of the earlier Americans respected Don Jose de Arnaz, and his descendants today are ranked as among the best people of Southern California. ….

Sheridan continues:

The Stevenson ruffians, finding that Arnaz would not permit them to loot the Mission, released him unharmed physically; but they made their camp in his home beside the San Buenaventura River and, before leaving, destroyed the furniture in the house – including a piano, the only one then in all California – and took all his horses and mules. In Los Angeles, the same men, or some others of the same regiment, looted his place of business, taking or destroying merchandise of all kinds.

Sheridan, p. 91.

In effect, they left him a financial wreck. He had to borrow money from the relatives of his wife to get enough to make his way north to the mines, where he hoped to find gold and recoup his fortunes. He was a man, however, who could not be kept down. And, reaching the mines, he found the same men who had seized upon his property in San Buenaventura selling his cattle and horses and mules to the miners.

Whether he recovered any of the stolen stock is not stated. He did find gold, apparently – or he found a way to make money. For he did not remain in the north very long before he was running a general merchandise store at Stockton; and had opened a bank for the convenience of the miners who desired to have their gold dust handled by responsible people.

Physician & Small Pox Savior

Sheridan writes that Arnaz was an “educated physician-although he never actively practiced. …. And the skill of Don Jose was always at the service of the early residents.” (Sheridan, p. 391.) “Arnaz … although he prescribed for the sick, and very likely furnished medicines also, never took one cent for his labors as a physician.” (Id. p. 90.) Elsewhere, Sheridan tells of an emergency in 1862 in which Don José did practice medicine:

During the great small pox epidemic in 1862, the first known appearance of disease in this section, he vaccinated most of the members of the leading Spanish families of the district. Then, sending a courier ahead to notify the people of the Pueblo that he was coming, he went to Los Angeles and treated many of his friends there who had been stricken.

Sheridan, pp. 91-92.

From Los Angeles he went to Pomona, thence to the Toro Rancho, in San Diego County, where he found that the entire family of the friend he had come so far to succor had died of the dread plague. Family, servants, vaqueros, everyone on the Rancho was gone. One lone Indian remained of all those who had formed the busy life of the place when Don Jose had last visited his friends there.

Joaquin Murietta

Many famous people became a part of the life of Don Jose de Arnaz. At the time that Joaquin Murietta was frightening people all over the country, he made a visit to the Rancho Arnaz adobe. It was very late at night and one of the Arnaz daughters heard the sound of water being drawn from the well that was just outside her window. She cautiously peeked out and, recognizing the noise makers as Murietta and his bandits, she warned her father, who with his sons, took up their positions with guns at various windows to guard their home.

Murietta and his men walked around the house, saw that it was too well-guarded and left without disturbing the family. However, the bandits took with them the Arnaz cattle, driving them toward the Ojai Valley. Arnaz and his sons organized a posse with their neighbors and started in pursuit. They overtook Murietta somewhere between the ranch and the Ojai Valley, recovering the stolen cattle while Murietta and his men escaped into the Sespe.

Ojai History website; mythologized in popular literature, Joaquin Murietta was killed by a group of California Rangers on July 25, 1853.

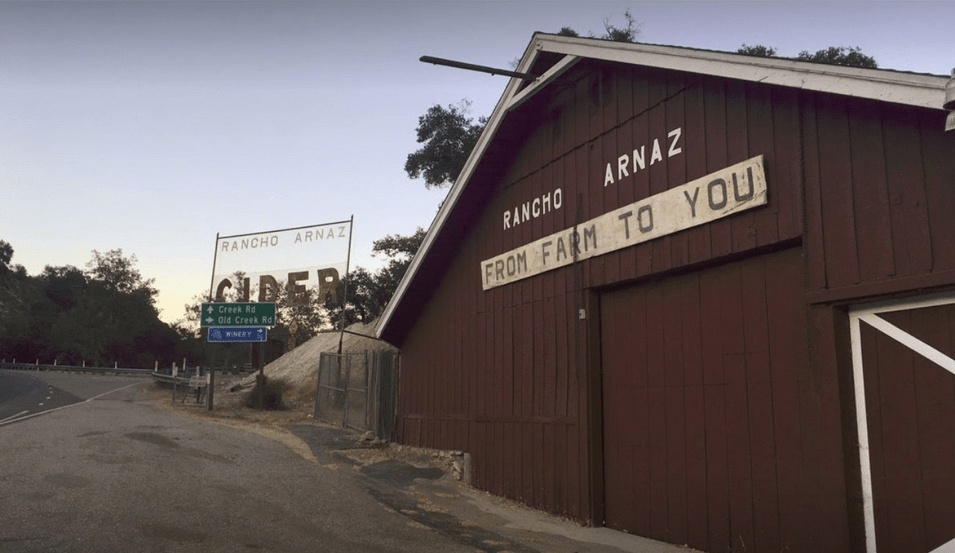

Arnaz Rancho (Santa Barbara/Ventura County)

According to Mason, in 1859, Arnaz was elected County Supervisor of the First District of Santa Barbara. (Mason, p. 115.) He served until at least June 1861. (Id. at 119.) He was also a Santa Barbara County road commissioner. (Id. at 118.) When Ventura County seceded from Santa Barbara County in 1873, Arnaz’ holdings went to the former. They would include his Rancho Arnaz, which was built in 1863 for Don José. Sheridan adds a couple more titles to Don Jose’s portfolio around that time.

He was back in San Buenaventura in the very early sixties, and we find him starting a flouring mill and a tannery, run by water power, on the bank of the San Buenaventura River at the point where the Coyote Creek comes into the river near the mouth of Casitas Pass. It was probably near about this time that he acquired his Santa Ana Rancho holdings.

Sheridan, p. 91.

The oldest continuously lived-in residence in the County. Typical adobe construction, modified into a Craftsman motif. Its original walls, beams and floors have survived many alterations. The house was built for Don Jose de Arnaz on the 21,522-acre ranch he bought in 1846 for $13,000.

Ventura County Historical Landmarks & Points of Interest (2012), p. 5.

As of 2023, Rancho Arnaz is the “Rancho Arnaz Horse Boarding Stables.“

Jose de Arnaz’ closest neighbor, Thomas R. Bard (1841-1915), was yet to be known as an oil pioneer (1867), Santa Barbara County Supervisor (1868-1871), or United States Senator (1900-1905), when, on January 3, 1866, he wrote his sister about renting a ‘ horse carriage (formerly the Governor Alvarado’s carriage) from an “old Spaniard,” “Old Don Jose de Arnaz,” for a trip to Santa Barbara:

Nearby our first well lives an old Spaniard the proprietor of an adjoining ranch, who is poor, but proud of his Castilian blood and very unfriendly to Americans generally. Old Don Jose de Arnaz and I, however, are quite good friends though we have quarreled many times over the price of sheep or his monthly bill for milk, etc. Still we are friends, and I knew he would not hesitate to hire his carriage to me if I wanted it. So, though it was late, I called to see the old fellow, hired his coach for three days for the modest sum of $25.00. Now that sounds a great deal of money; but you must know that Don Jose particularly reminded me at the time that this was at one time the carriage of the old Mexican Governor [Juan] Alvarado, and used by him and his family long ago, before the conquest by Americans, under Fremont, of Alta California.’”

Ventura County Historical Society Quarterly (Winter 1981) pp. 8-9.

By the next year (1877), Bard would be “credited as the wealthiest man in Ventura” (Mason, p. 371), so he could afford to pay his neighbor – whom he called the “old Spaniard,” “Old Don Jose,” and the “old fellow.” When Bard wrote the above letter, he was 25 years old, and Don Jose was all of 45 years old.

Widowed – 1867

On about Christmas Day, 1867, Doña Maria Mercedes Abila de Arnaz died. She was 35 years old, and had given birth to twelve children during her 20-year marriage to Don José. Don Jose listed them in his will as follows: “Virginia, Elvira, Luis, Adela, Amada, Ventura, Manuel, Maclovio, Camila, Jose Maria, Eduardo and Mercedes; Adela, Camila and Mercedes are now dead.” (Arnaz’ will, as translated from Spanish in the Ventura County Historical Society Quarterly, Summer 1981.) Romance of a Rancho, omitted Manuel and Eduardo Arnaz from the list in 1939, stating “Children by his first wife were Elvira Arnaz and Ventura Arnaz Wagner, both living in Ventura; McIvio Arnaz, of Salinas; Amanda Arnaz Sepulveda, of Los Angeles; Virginia de Anguisola, Adella, Camilla, Mercedes, Jose Maria, and Luis, all deceased.”

Litigation over Merced Abila’s Estate

Shortly before her death, Merced Abila (as she was also called) executed a will leaving her property to her children and making Don José her executor. Her death was followed by litigation to enforce her will, creating the following historical record. In 1872,

Manual Anguisola, the husband of a daughter [Virginia] of deceased, presented to the Probate Court a petition for an order to produce the will, and also to be appointed administrator with the will annexed. Jose Arnaz produced the will, in which he was named executor, and also applied to have letters testamentary issued to him. Anguisola contested his right to be appointed, both because he was an improper person, and because of his neglect in presenting the will for probate. The Probate Court denied Anguisola’s application, and appointed Jose Arnaz. Anguisola appealed, both from the order refusing to grant him letters and from the order granting letters to Arnaz.

Estate of Arnaz (1873) 45 Cal. 259.

In January 1873 the California Supreme Court left the Probate Court’s order intact, so José de Arnaz remained in control of all of the property. The decision was made, at least, for procedural reasons:

This Court will not review the evidence in a proceeding in the Probate Court, unless it is embodied in a statement on appeal, as provided for by section two hundred and ninety-nine of the Probate Act.

Estate of Arnaz (1873) 45 Cal. 259, 260.

Son-in-law Manuel Anguisola returned to court on May 23, 1874 (this time with two Arnaz children, Elvira and Adela) alleging that the property Don José bought after he married Señorita Abila was all hers because he had used her separate property to pay for it. Manuel filed in the District Court (not the Probate Court), and he won.

In the District Court, the children alleged that:

- When José de Arnaz married Merced Abila in 1847, he had no property (real or personal) of his own.

- In 1848 or 1849, Merced inherited and was gifted, from her uncle, Antonio Ygnacio Abila, and from other relatives, as her separate property, six hundred head of cattle, three hundred horses, ten mules, ten oxen, and four thousand dollars in money.

Merced’s uncle was likely Don Antonio Ygnacio Avila (1781-1858) – the grantee of Rancho Sausal Redondo – which encompasses the present-day cities of Redondo Beach, Inglewood, Hawthorne, El Segundo, Lawndale, Manhattan Beach, and Hermosa Beach. The children further alleged that José had used his wife’s property to buy the following:

- One-sixth interest in Rancho Santa Ana in 1854. (The date differs from accounts in Ventura County Historical Landmarks & Points of Interest (he paid $13,000 in 1846 for the 21,522 acre ranch) and from Sheridan’s version: “He was back in San Buenaventura in the very early sixties …. It was probably near about this time that he acquired his Santa Ana Rancho holdings.” (Sheridan, p. 91.))

- One-half interest in Rancho Rincon de Los Bueyes in 1855. (The date differs from other records, which show him buying Secondino Higuera’s undivided half-interest in 1849 and Francisco Higuera’s interest in 1867.)

- 400 varas of the Rancho San Jose in 1858, which he sold in 1868 for $600.

The children also alleged that, after Merced’s 1867 death, Don José:

- Used the increase of livestock and the rents and profits from real estate to buy three thousand sheep, which he sold (in 1869 or 1870) for $9000.

- Sold some livestock and land to support himself and his family, and to pay taxes and expenses. Specifically, he sold seventy-five acres of said Rancho Santa Ana for $550 in 1872 and a large parcel of said Rancho Santa Ana for $15,000 in 1873.

Finding in favor of the children and against Don José, the District Court decreed all property would be distributed to the children after the court took an accounting. Don José appealed.

In July 1876, the California Supreme Court reversed the District Court, holding that Merced had put all control in Don José’s hands and, if he was abusing it, that claim had to go to the Probate Court, not the District Court. (De Auguisola v. De Arnaz (1876) 51 Cal. 435, 438-439.) Don José was left to handle the property as he wished.

In his 1890 will, Don José would tell a distinctly different story about his property, claiming he made nothing in his first marriage:

I declare that during my first marriage I had no gains but large losses indeed, owing to the bad year from 1863 to 1864 in which all our animals died: away went our fortunes!”

Don José also declared that the land he ultimately owned traced back to personal property he had before his first marriage:

I declare that I have some properties acquired with the personal property I had before my first marriage, which I bequeath in the following manner: … property in the Rancho Rincon de las Buelles

all the property that I own in the County of Ventura known by the name of Casa Vieja de Arnaz and Casa de Anguisola … seven more acres that I own in Rancho Ojai, now lent to Teodoro Lopez.

Marriage to Maria Camarillo

In 1868, less than a year after losing Merced Abila, Don José married Maria Camarillo (1848-1916) the “sister of Don Adolfo Camarillo of Camarillo.” (Sheridan, p. 87.) “Mrs. Arnaz was a native daughter, born at the rancho of her farther, Don Juan Camarillo, in Ventura county in 1848.” (October 12, 1916, LA Times.) Maria was about 20; he was 28 years her senior. Maria’s seven children from their 28-year union are listed in his will:

I declare that I was married the second time to Dona Maria Camarillo de Arnaz, of which marriage I had seven children and they are Praxidio, Pragedes, Juan Nisefero, Alfonso, Jose Adolfo, Adela and Edilberto.

Variants of names:

Mrs. Adela (or Adelia) Arnaz de Stelle

Mrs. Amada (or Amanda) Arnaz de Sepulveda

Miss Elvira (Minita) Arnaz

Luis (Louis) Arnaz Arnaz

Mrs. Praxidio Arnaz de Lavin

Mrs. Ventura Arnaz de Wagner (Mrs. John Wagner)

Mrs. Virginia Arnaz de Anguisola

Don José’s will and addendum, as translated from Spanish in the Ventura County Historical Society Quarterly, Summer 1981.

The Ventura County Historical Society Quarterly included an addendum to the will, with Variants of names:

Mrs. Adela (or Adelia) Arnaz de Stelle

Mrs. Amada (or Amanda) Arnaz de Sepulveda

Miss Elvira (Minita) Arnaz

Luis (Louis) Arnaz Arnaz

Mrs. Praxidio Arnaz de Lavin

Mrs. Ventura Arnaz de Wagner (Mrs. John Wagner)

Mrs. Virginia Arnaz de Anguisola

By one account, Don José fathered another child: Maria del Rosario, by Maria Dolores Chihuya (?-1864):

Maria Dolores, another daughter of Odón Chihuya and Juana Eusebia, was first married to a San Fernando Indian named José “Polo,” then lived with José Arnaz, recipient of the San Buenaventura Ex-Mission grant, before finally settling down with Pierre Domec, a Frenchman who operated a lime kiln operation near El Escorpión. Her eldest daughter, Maria del Rosario, was said to be the daughter of José Arnaz, according to Fernando Librado, one of J. P. Harrington‘s Ventureño Chumash consultants, although her baptismal entry states that she was the son [sic] of Maria Dolores’s first husband, José “Polo.”

John R. Johnson, The Indians of Mission San Fernando, Southern California Quarterly, vol. 79, no. 3, Fall 1997, p. 269, citing Travis Hudson, Breath of the Sun: Life in Early California as Told by a Chumash Indian, Fernando Librado to John P. Harrington (Banning: Malki Museum Press, 1979), p. 92; SFe Bap. 3027.)

Don José’s putative consort, “Maria Dolores [was] one of the three daughters of Odón Chihuya [a.k.a. José Odon] who was one of the three Chumash who were the grantees of the Mexican Period El Escorpion land-grant, today’s Bell Canyon.” (The West San Fernando Valley Lime Industry and Native American History.) “History shows that Odon was not just the head of his household, but also the leader of the native west valley community (Johnson 1997:269).” (Albert Knight, The History of the West San Fernando Valley Limestone Industry and the People that Operated It (June 26, 2017) p. 15.)

There is reason to doubt Fernando Librado‘s story. Librado, at an advanced age when John P. Harrington interviewed him, could have confused facts, and it is fair to assume that Librado had little affection for the man who took control over the mission where he lived and where natives considered themselves slaves. (Breath of the Sun, p. 91, fn. 1.) Librado’s reference to Arnaz wife “Arenas” does not match either of Arnaz’ wives. “After leaving María [Dolores], José Arnaz returned to Ventura for a third time. He was married to a Los Angeles lady named Arenas. This was the time when he bamboozled people out of Ranch No. One up the Avenue [Ventura Avenue].” (Breath of the Sun, p. 92.) And this writer has found no other record of Arnaz marrying a Los Angeles lady or one named Arenas – or of him bamboozling.

For 1873, Mason lists Arnaz as owning 6,000 acres of land in Santa Barbara County. (Mason, p. 361.) A local paper, the Pacific Rural Press (1871-1922), described the property and said Don José wanted to sell:

Adjoining Mr. Bard’s, on the north side of the stream, is the estate of Don Jose de Arnaz, some 6,000 acres of hill, valley and woodland, 2,500 acres of which is cultivated land. The Don lives in primitive style and speaks no English – subsisting off the product of his flocks. Surrounded on all sides by the encroaching Anglo Saxon, it is not strange that he is dissatisfied and wants to sell – demands $16,000. So pass away the old “patrones;” the $16,000 is probably only enough to cover the mortgage and leave a modicum to go to less ample quarters with. As long as any of the simple original possessors have a foot of soil, the traders will sell them goods, and when the bill is getting too large take a mortgage. That is the River Styx to them financially, and is never recrossed. The mortgage is seldom redeemed, and the broad acres go to Shylock.

Pacific Rural Express (published 1871-1922), January 11, 1873.

A Wikipedia entry on Rancho Santa Ana reports (currently without any citation) that in 1874, “Arnaz sold the land to sea captain Richard Robinson, Judge Eugene Fawcett, Jr., and H.C. Dean, who subdivided the land and started the development of the Ventura River Valley.” Mason (at p. 418) wrote in 1883, “This forest-hooded rancho is principally owned by R. G. de la Riva, Captain Robinson, and Messrs. Fawcett and Dean.”

Arnaz apparently kept interests in the Buenaventura area, since he paid $19,407 in taxes there in 1874 (Mason, p. 364) and over $15,000 in 1876 (Mason, p. 369). He was also one of several who petitioned for a breakwater for the San Buenaventura Wharf in 1877. (Id., p. 370.) Also in 1877, Don José helped establish a school in Ventura County:

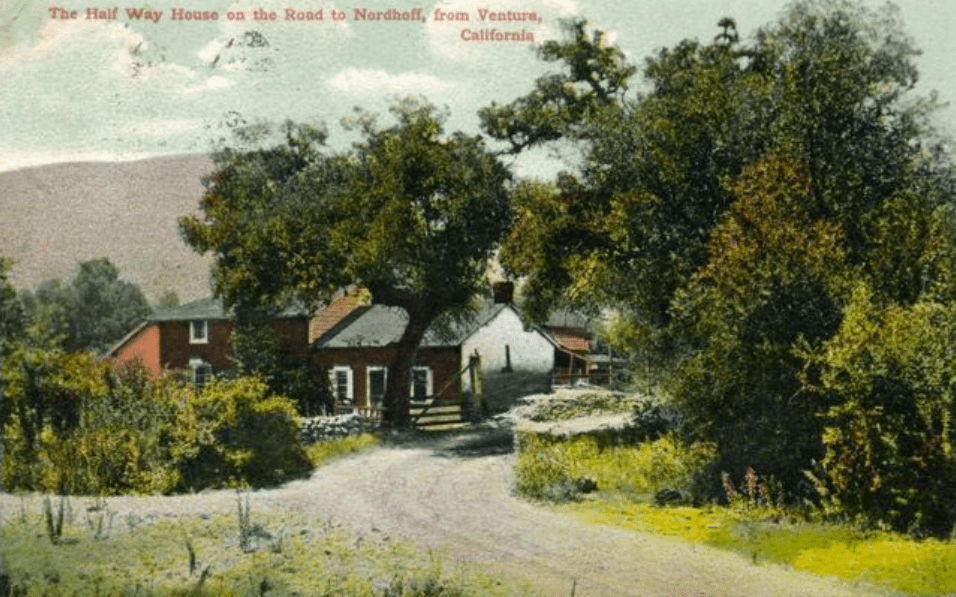

In 1877 Don Jose Arnaz gave the County Superintendent of Schools (S. S. Buchman) the use of one room in his home for a school. In the course of time, a schoolhouse was built on the Creek Road north of the old Arnaz Ranch house. The land was donated by Mr. Arnaz. The building was first occupied as a school in 1893 and became the center of social activities in that area.

A Historical Study of the Nordhoff Union School District, by Russell Adolph Vogel (Aug. 1963) p. 28.

Move to Los Angeles (1885)

In 1885, Arnaz moved his family south to Los Angeles County, where he would reside for the rest of his life.

From San Jose, with his growing family, Arnaz moved back to Los Angeles, and when litigation in connection with Rancho Rincon de los Bueyes was finally settled, he constructed the 15-room house which became a showplace. To the housewarming, which also marked the sixteenth birthday of his daughter, Prexcedes … he invited everybody from what is now Western avenue to the sea. Over 200 guests sipped his wines and danced throughout the night.

Romance of a Rancho.

Don José established a 3100-acre rancho in rural Los Angeles County, where he raised cattle and grew grapes (among other crops). It covered most of Rancho Rincón de los Bueyes, which he bought from Secundino Higuera (in 1849) and Francisco Higuera (in 1867), the sons/heirs of the rancho’s original grantee, Bernardo Higuera. At the time, the area was called Ballona, Ballona Valley, The Palms, and Cahuenga Valley. The ranch, in the context of modern streets, covered much of the area below Pico Boulevard and Airdrome Street on the north, between Manning Avenue on the west and Genesee & Fairfax Avenues on the east. (“The Palms” subdivision (1886) was on land south of Arnaz’.)

Arnaz had a long connection with the El Pueblo de Nuestra Señora la Reina de los Ángeles. As noted above, in 1848, he had an orchard and vineyard and vineyard in Los Angeles which Colonel Jonathan D. Stevenson’s troops looted and burned. The City had granted him property in Los Angeles in 1847:

Mr. Manuel Requena, member of the Police Committee submitted a report concluding with the following resolution: “The Common Council of this City sustains the validity of the resolution of the late Town Council adopted on the 16th day of October, 1847, which granted Dn José Arnaz a certain lot situate back of the house of Da Josefa Cota and measuring fifty varas front by forty varas (yards) in depth.”

October 9, 1850, Common Council minutes.

Don José de Arnaz died on February 1, 1895 “At The Palms.” (L.A. Times, Feb. 4, 1895.) The Los Angeles Herald reported: “Funeral from his late residence Monday, February 4th, at 8 a.m. thence to Cathedral, where solemn requiem mass will be held. Interment at Calvary cemetery. Friends invited.” (L.A. Herald, Feb. 4, 1895.) Since “New Calvary Cemetery” (in East Los Angeles) was not dedicated until 1896, he was likely reinterred there when the Los Angeles Archdiocese moved the Calvary Cemetery.

Soon after his death, Merced Abila and Don José’s children finally received a distribution of her land (or its value). However, in October 1898, a granddaughter, Mercedes Anguisola, sued saying she was “fraudulently deprived of a legacy by the executrix of the will,” Doña Maria Camarillo de Arnaz. (L.A. Times, Oct. 6, 1898.) Mercedes Anguisola’s parents were Virginia Arnaz de Anguisola and Manuel Anguisola (who, as Virginia’s widower, had litigated concerning his mother-in-law Merced Arnaz’ estate). (The L.A. Herald, Oct. 6, 1898, wrongly reported the plaintiff was Arnaz’ daughter, but Mercedes was his granddaughter.) Mercedes claimed she was entitled to $500 upon her marriage. On October 23, 1898, the Los Angeles Herald reported that she had obtained a marriage license.) How that litigation ended is not currently known to this writer, but the rest of the story of Don José’s Los Angeles County Ranch is told on another page on this site.

Doña Maria Camarillo de Arnaz died in Hollywood, California on October 11, 1916. Her obituary wrongly says Don José had died in 1905 and is apparently just as wrong in saying that he “commanded the Federal troops at Ventura, following the taking of that city, by Gen. John C. Fremont. He was one of the most prominent surgeons in the State prior to his death.” It does contain names and addresses of Arnaz’ heirs that historians might find useful.