Cheviot Hills Recreation Center

The Spanish Rancho years and beyond

(1821-1920)

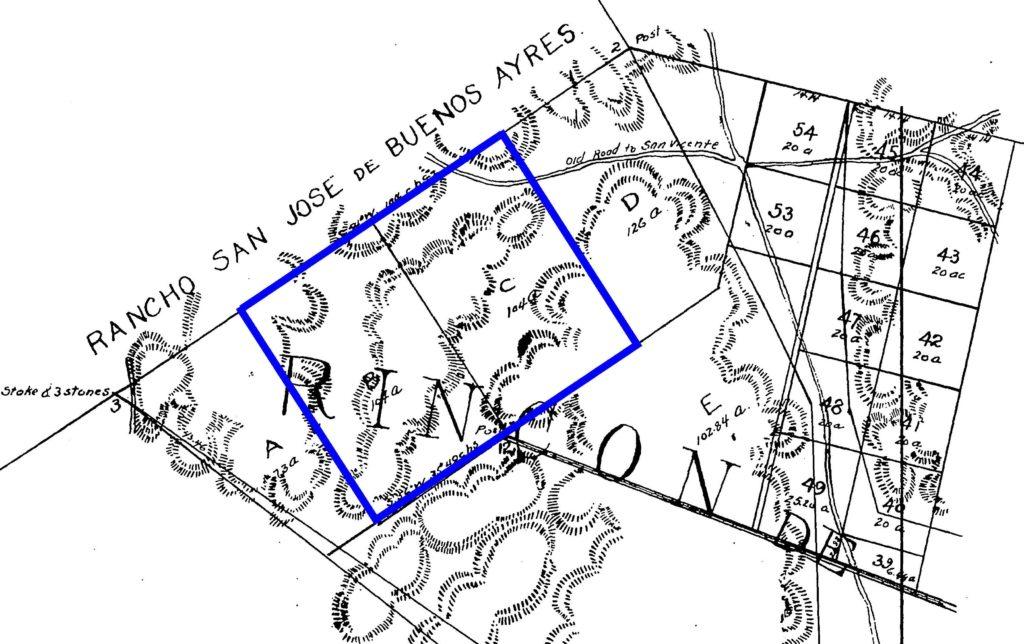

The Cheviot Hills Recreation Center and its Rancho Park Golf Course sit on an 1821 Spanish land grant: Rancho Rincón de los Bueyes. Don José de Arnaz bought sections of the rancho from grantee Bernardo Higuera’s sons: from Secundino Higuera in 1849 and Francisco Higuera in 1867. By 1875, Arnaz had subdivided the hilly northwest sections of the grant into Lots A through E, ranging from 73 to 126 acres. After passing through a few more owners, Lots B and C (shown as 104 acres each) would become the bulk of the Recreation Center land.

On April 25, 1896, a court divided Lots A, B, C, and E of the Arnaz ranch among the children/devisees of the late José de Arnaz (1820-1895) and his first wife, Maria Mercedes de Avila (1832-1867). (In 1876, the California Supreme Court had rebuffed the children’s effort to get the land earlier.)

On May 21, 1896, Arnaz’ inheritors conveyed Lot E for $4,500 (about $44 an acre) to Arthur F. Gilmore; on May 27, 1896, Gilmore got Lot A for $3,640 (about $35 an acre); Lot D for $3,640 (about $35 an acre); and he took Lot C on July 29, 1896, for $4,700 (about $45 an acre). Gilmore (1850-1918) was a dairy farmer who had struck oil while drilling for water. His son, Earl B. Gilmore (1887-1964), developed Gilmore Oil Company. The family still owns Farmers Market at Third and Fairfax.

In July 1905, the Burkhard Investment Company (a family corporation formed in 1912 by Joseph Burkhard (1848-1928)) bought Lots B, C, and E from Arthur F. Gilmore (through Gilmore’s agent Charles Stilson) for about $200 an acre. (Most of Lot E would make up the Monte-Mar Vista subdivision.)

S. W. Straus & Co.’s Ambassador & Rancho Golf Clubs

(1920-1933)

Frederick William Straus (1833-1898) was a German Jewish immigrant to Lingonier, Indiana in 1854. Starting as a peddler, he became a retailer, buggy manufacturer, realtor, and banker. In 1882, Straus established the business of selling first mortgages on small, improved property. In 1895, he was joined by his eldest son Simon William Straus (1866-1930), and together the family operated several corporations under the name S. W. Straus & Co. The company helped finance the booming construction in major American cities in the early 20th century. The American Architect (Jan 25, 1926).

On May 26, 1920, a Straus company bought an 187-acre parcel from Burkhard Investment Company for $1200 an acre as the site for a country club and golf course for its Los Angeles’ Ambassador Hotel and Alexandria Hotel patrons. (The buyer’s attorney, Henry William O’Melveny, became its first president.)

The Ambassador Golf Club opened on July 26, 1921. William Herbert Fowler (1856-1941) designed the golf course, and Ambassador Hotel architect Myron Hunt designed the clubhouse. According to golf historian John “J. I. B.” Jones‘ “Rancho Park History 1921-2008,” Fowler laid out an 18-hole, par-72, 6,250-yard-long, golf course that made full use of the many hills, ditches, and arroyos. Over the years, the course was reconfigured as detailed by Jones.

During planning stages, in June 1920, news reports referenced the Rancho Golf Club. Upon opening, it was called the Ambassador Golf Club. Within a year it went back to the “Rancho” name: a May 1922 article reported on “the Rancho Golf Club, formerly the Ambassador course.”

In May 16, 1923, the Ambassador Golf Club area was annexed into the City of Los Angeles in the so-called Ambassador Addition. According to golf historian Jones, that meant

a reliable city water supply which allowed the club to hire contractor / architect Billy Bell to refurbish the original Fowler course that included installing a new irrigation system that could better grow grass on the bare hills while also enlarging some tees and widening some of the fairways.

Rancho Park History 1921-2008.

Jones also writes that,

In 1923 the Rancho Golf Club signed a 10-year lease for the course and buildings, and went on to field the trophy-winning Southern California Golf Association Team-Play champions of the 1920s, with [Paul M.] Hunter [1890-1944], [George] Von Elm [1901-1961], Howard Hughes [1905-1976], Charles [Leon “Chief”] Soldani [1893-1968] [Osage Nation member who acted in hundreds of movies], [Charles] Leon Keller [1905-1931] [he lived steps from Rancho at 10544 Ayers Avenue in Country Club Highlands], Bruce [Ford] Bundy (1893-1939), and [Warren Wallace] Beckwith (1875-1955) [his first wife was Jessie Harlan Lincoln, Abraham Lincoln‘s granddaughter], on the winning teams.

The Rancho course was also home to the Los Angeles Athletic Club, before the opening of their own course, the Riviera Country Club, in 1927.

Rancho Golf Club 1921-1950, for the Golf Historical Society.

The press covered celebrities who convened at the country club, including golfer (and future billionaire industrialist) Howard Hughes, who made movie business deals at Rancho. The February 16, 1931, San Francisco Examiner reported: “Thursday morning at exactly 10 o’clock at the Rancho Golf Club Messrs. [Edward Bennett] Derr and [Charles] Sullivan put an end to all rumors by signing with Hughes” to be “in charge of all production activities for Caddo,” Hughes’ movie production business.

While Hollywood was still doing business, the 1929 stock market crash, and the ensuing Great Depression, toppled the Straus family businesses and led to the United States government owning their country club land. A 1935 court decision on the liquidation of the Straus interests relates the following:

In 1882 Frederick W. Straus established the business of selling first mortgages on small improved property in Chicago. In 1895 he was joined by his son, Simon W. Straus, and the firm of S. W. Straus & Co. was organized. …. In 1916 S. W. Straus & Co., Incorporated, was organized under the laws of the State of New York. Having then been in business thirty-four years, it adopted the slogan: “34 Years in Business Without Loss to Any Investor.” That slogan continued – the number of years annually changing from 34 to 45 – until 1927 when it was discontinued. The legend remained true in fact until February 1, 1931. Until then there had been no loss to any investor.

The corporation, from its formation in 1882 to 1924, sold only first mortgage bonds, with a single exception, but, without informing the public of the change in policy, thereafter gradually included in its offerings bonds secured by leasehold mortgages, second and third mortgages called “general mortgages,” collateral trust bonds secured by an assortment of subordinate mortgages owned by the borrower, and debentures of corporations owning real estate obligations wholly unsecured.

Defaults commenced in 1931, following the financial crisis of 1929, and by the end of 1932 practically all such bonds were in default.

The financial crisis took a toll on the Straus family. Simon W. Straus died on September 7, 1930, after a long illness. His son-in-law, Herbert Spencer Martin (1883-1930), who was a vice-president of S. W. Straus and Company, “was killed … in a fall from an eight-story window of his Park avenue apartment.” (The Evening News, Jan. 14, 1930.) Then Straus’ nephew, Walter Simon Klee (1884-1932), recently a vice-president and director at S. W. Straus & Co., died after swallowing “poison tablets” after suffering from “poor health, despondence and discouragement over business conditions.” (New York Times, May 12, 1932.)

The Straus enterprises were left with a mountain of unpaid taxes going back to 1920. As “security for the payment of $826,703.84 taxes,” the Commissioner of Internal Revenue took an April 12, 1933, deed of trust on the Rancho Golf Club (as well as some of Straus’ interest in Chicago). (Aug. 17, 1934 U. S. Comptroller General opinion for U. S. Treasury Secretary.) When the taxes remained unpaid, the Rancho property went into receivership. The Straus’ customers were also left in the lurch: “On the date of the receivership, March 3, 1933, there were $360,000,000 bonds unpaid, held by 80,000 bondholders.”

Federal Ownership

(1933-1946)

The Straus interests were given until the end of 1933 to redeem the property by paying their federal tax debt, but they reportedly said they would abandon it instead. And the City of Los Angeles could not (yet) afford to care for or buy it. (L. A. Times, Oct. 27, 1933.) In Fall 1933, before the course was ruined by a lack of maintenance since the August 1933 land seizure, the United States Golf Association (USGA) leased the land from the Commissioner of Internal Revenue. Southern California “Public Links” representative Alan La Verne Nichols (1890-1942) took over management and hired William P. “Billy” Bell (1886–1953) to maintain the course. In February 1934 the Rancho Public Golf Course re-opened with a day of free golf. (Rancho Park History 1921-2008.)

In January 1934, because the Internal Revenue Commissioner could only sell the Rancho club for a fraction of its value (appraised in October 1933 at $500,000), he entered into another trust agreement providing that

the Commissioner of Internal Revenue, as trustee, would make no sale or conveyance of the properties prior to January 1, 1937, without the written consent of the Rancho Golf Club … and Samuel [Jones Tilden] Straus [1876-1942], Chicago, Ill., or in the event of his death or disability, by certain other named members of the Straus family.

Comptroller General’s 1934 opinion for the Secretary of Treasury (Samuel Straus was a younger brother of the late Simon W. Straus.)

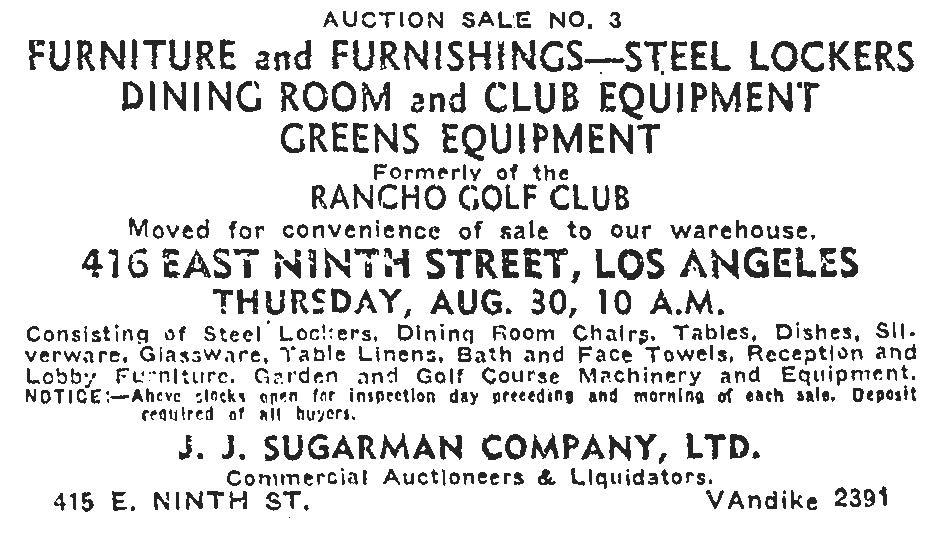

Meanwhile, on August 30, 1934, the Revenue Service did auction off the club’s furniture, silverware, and course maintenance equipment.

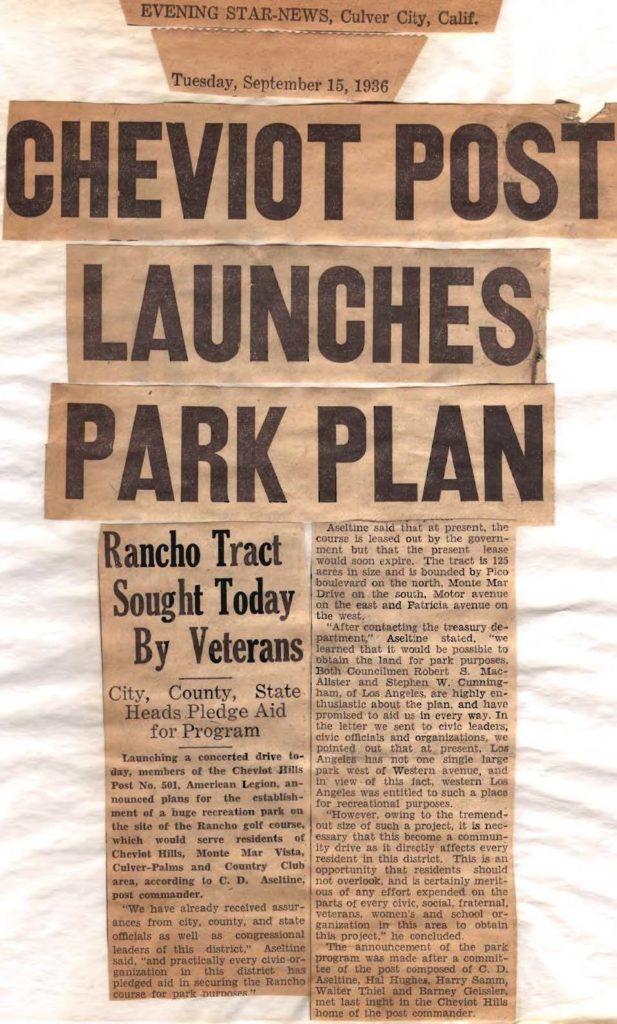

The course’s neighbors took notice; they did not want the land sold off and redeveloped. On September 15, 1936, with the USGA’s lease set to expire, Cheviot Hills American Legion post #501 commander C. D. “Ace” Aseltine launched a drive to establish a recreation park on the site of the bankrupt Rancho Country Club. The Legionnaires pointed out that

Los Angeles [had] not one single large park west of Western Avenue, and in view of this fact, Western Los Angeles was entitled to such a place for recreational purposes.

Evening Star News (Sept. 15, 1936)

The American Legion post history shows them gathering support from civic leaders including city councilmembers, county supervisors, Congressman John F. Dockweiler (1895-1943), Hamilton High School faculty, the Emerson and Overland schools’ PTAs, and numerous other civic organizations, as well as the other American Legion posts. The campaign took their long commitment.

In January 1939, area congressmen planned federal legislation to authorize trading federally-held Rancho land for Reeves Field on Terminal Island. Formerly Allen Field Terminal Island Airport, Reeves Field had been San Pedro’s municipal airport, and the City of Los Angeles was leasing it to the federal government for an Army and Navy airfield. (For an excellent history of the airport (and others) see Abandoned & Little-Known Airfields website.) The March 13, 1939, Congressional Record shows the City of Los Angeles facilitating the process with a “Resolution of the Board of Playground and Recreation Commissioners of the City of Los Angeles, relating to a proposition which, if enacted, would grant Reeves Field, now owned by the city of Los Angeles, to the United States Navy, etc.” referred to the Committee on Public Lands. However, the trade was not concluded. Indeed, another Congressional Record shows a 1940 federal threat to “expropriate Reeves’ Field Airport” because it was on reclaimed land.

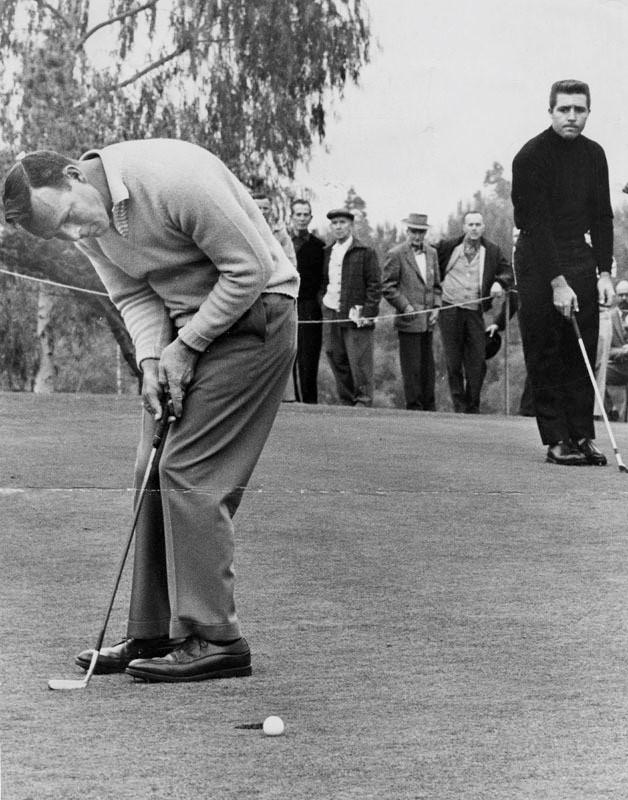

Meanwhile, the public continued to visit Rancho, as shown in the photograph below from a tournament raising funds to finance a trip east for the Los Angeles Public Links team.

When the Revenue Service Commissioner decided the time was right to sell, various creditors – including the city, county, state, school district, and other tax-levying districts – had claims against the Rancho property. On July 8, 1942, the United States Attorney sued to clear title, alleging (according to the Los Angeles Times) that “club owners and operators owe the Federal government $831,703 in taxes and that the government’s claims to title to the property should take precedence.” Along with the taxing authorities, the defendants included Nomis-Suarts Corp. (owner of the Ambassador Hotel & Investment Corporation stock which, in turn, owned the Rancho Golf Club stock), Winifred Nichols (wife of A. Laverne Nichols, general manager under the USGA lease, who had died on June 5, 1942), and Cheviot Hills Post No. 501, American Legion (which leased the clubhouse for meetings).

The USGA stopped operating Rancho at the end of 1942, but the Commissioner kept the club running. On September 27, 1942, the Los Angeles Times announced that the Bureau of Internal Revenue would accept bids for a three-year lease of Rancho, beginning on December 1, 1942. Before then, in November 1942 (six years after the American Legion post began its campaign), it was announced that the City of Los Angeles would enter into a three-year lease of the Rancho golf course from the Federal Government and begin converting it “into a park and recreation center similar to that of Griffith park.”

It took four years for the federal government’s lawsuit to be resolved. On January 8, 1946, the Los Angeles Times reported that the City had agreed to buy the course, and, on March 8, 1946, it reported settlement of the federal lawsuit clearing title to the property: “Under the settlement, the city will take title upon payment of $200,000 to the Collector of Internal Revenue.” Historian Jones reports a higher price: “The Golf division of the Recreation and Parks Department of the City of Los Angeles purchased the old Rancho Golf Club for $225,643, mostly to cover overdue Los Angeles County tax bills in 1946” with the money coming from “surplus revenues from the operation of other city golf courses, principally those of Griffith Park.” (The Rancho Golf Course Opening (1949).) The March 7, 1946, Los Angeles City Council minutes reveal an additional consideration to the federal government: “6-1/4% of the amount or value of oil or gas that may be produced.”

Groundbreaking for the new, public, recreation center and golf courses was set for March 23, 1946, nearly ten years after Ace Aseltine and the American Legion began their effort.

City of Los Angeles Ownership

(1946 to present)

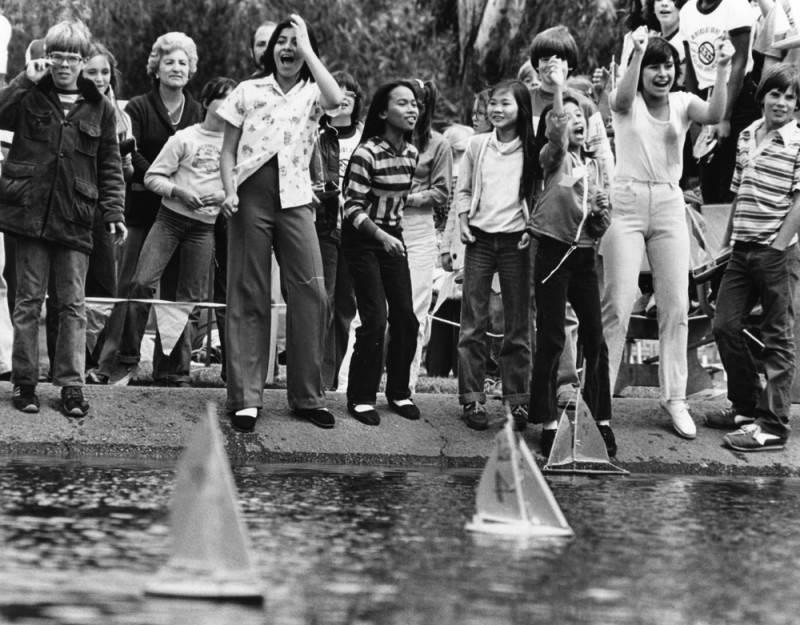

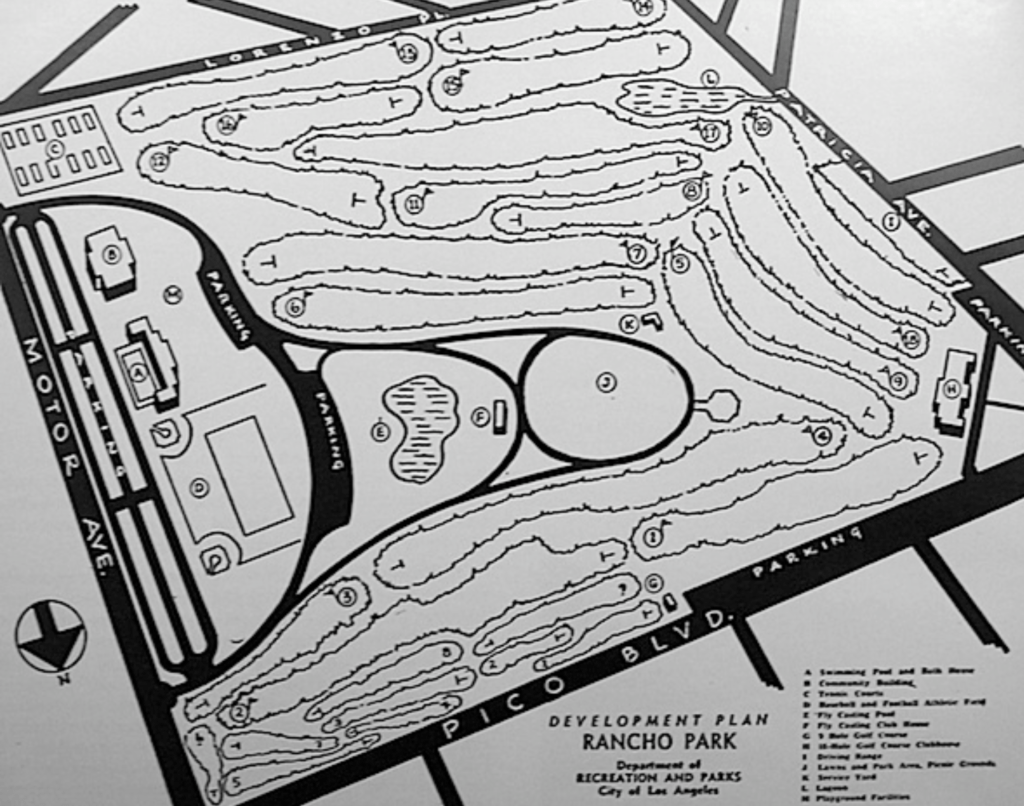

After “three years of construction and ‘one and quarter million cubic yards of earth’ moved” the private Rancho Country Club became the public Cheviot Hills Recreation Center. (The Rancho Golf Course Opening (1949).) It included the Rancho Park Golf Course, “an 18-hole, par 71 championship course playing at 6,630 yards, designed by William Johnson and William P. Bell” which opened with the 1949 U.S.G.A. Public Links Championship. (The City of Los Angeles Golf Division reports that it hosted 18 Los Angeles Opens and numerous LPGA and Senior tour events between 1978 and 1994.) The City also added the 9-hole Rancho Park 3-Par Golf Course (opened in 1948 and also designed by Johnson & Bell), a double decked driving range, several putting greens, and a new clubhouse (designed by George M. Lindsey (1891-1973)) with a “lounge, coffee shop and dining room, dressing rooms, lockers, showers, golf shop, starters and a manager’s offices and other facilities.” There would also be a 40-acre park including a Dwight Gibbs (1892-1983)-designed “modern swimming pool, bathhouse and community clubhouse” along with an indoor gym, 5 ball diamonds, basketball courts, children’s play areas, a football field, an outdoor gym, a picnic area, a soccer field, 14 tennis courts, an archery range, a band shell, and a (now gone) fly-casting pond.

On May 29, 1957, the City of Los Angeles leased land within the park to Signal Oil and Gas Company and Richfield Oil Corporation for oil and gas production. The city generally took a 20 percent royalty, from which it would pay the federal government’s 6-1/4 percent. They signed a further lease on December 28, 1960. In 1994, the leases, set to expire on May 28, 1992, were extended to May 28, 2027, this time with the Hillcrest Beverly Oil Corporation.