The Historic Ranchos

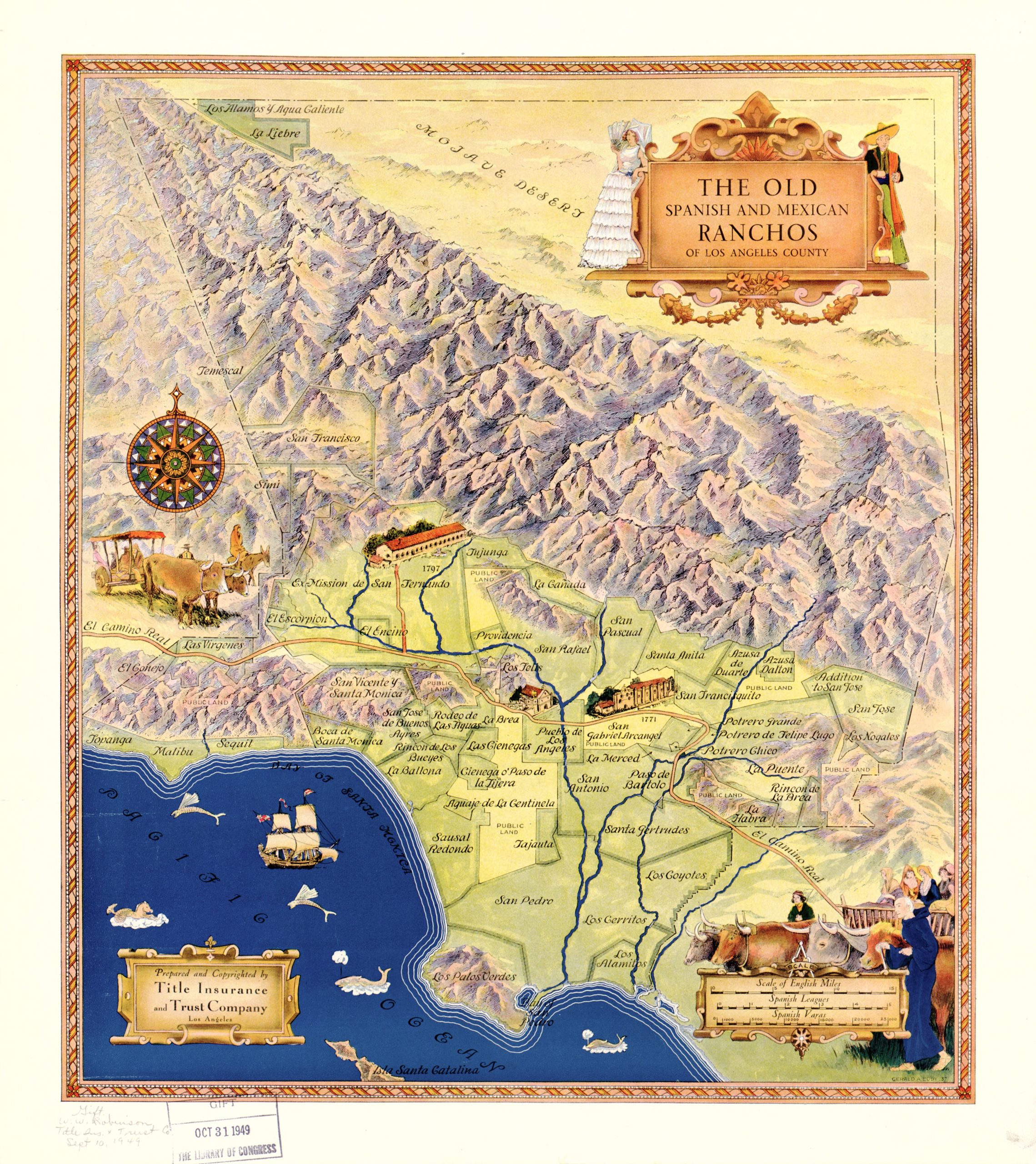

After conquering the Aztec Empire in 1521, the Spanish Empire established New Spain and claimed most of The Americas, including The Californias.

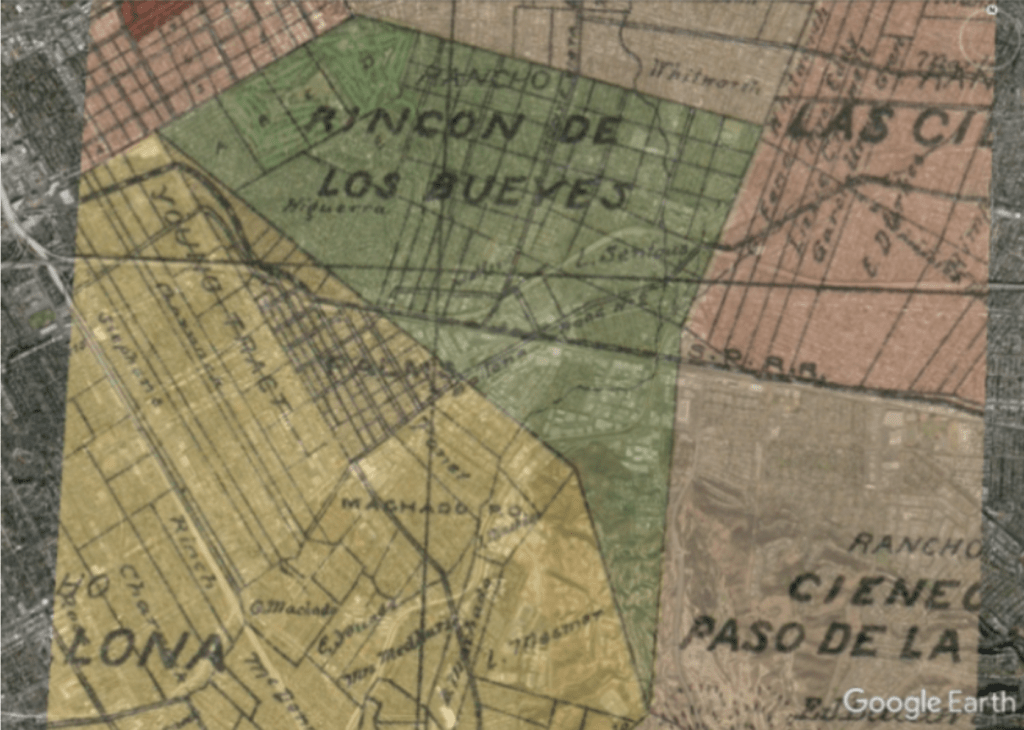

In December 1821, Spain’s military commander José de la Guerra y Noriega (1779-1858) granted Rancho Rincón de los Bueyes to Bernardo Higuera and Cornelio Maria Lopez. The grant may have been complicated by the fact that Mexico claimed independence months earlier, so it might not have been Spain’s to give away. Almost two decades later, Mexico, which had taken the area from Spain, granted nearby Rancho La Ballona to brothers José Agustín Antonio Machado (1794-1865) and José Ygnacio Antonio Machado (1797-1878) and to father and son Felipe Talamantes (1772-1856) and Tomás Talamantes (1793-1875).

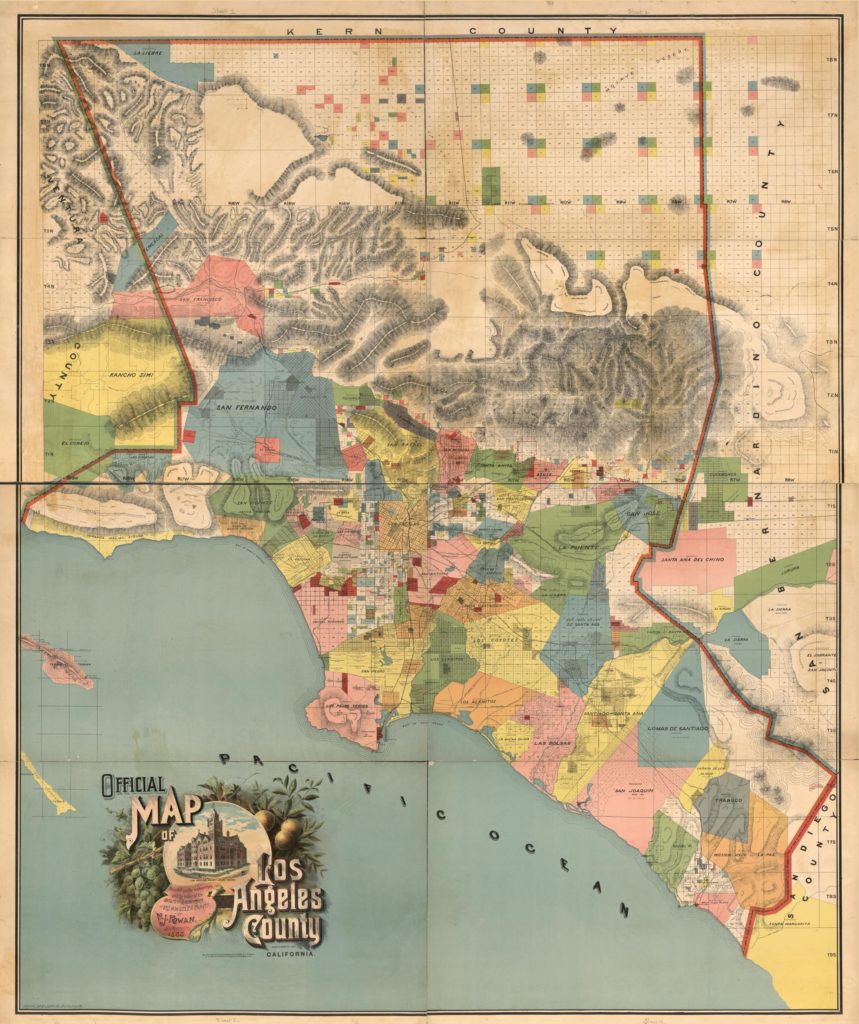

In West Los Angeles, the Cheviot Hills neighborhood, Castle Heights, Cheviot Hills, Monte Mar Vista, California Country Club Estates, and smaller tracts, are wholly within the former. In turn, Cheviot Knolls and Tract 10440 are entirely within the latter. Only Country Club Highlands occupies parts of both.

The Palms (1886) and Westwood Gardens (1944) are entirely within Rancho La Ballona.

Following is a brief history of these two ranchos through to their residential development. Mostly, it is names and dates – who got what parcel of land, when, and why. An effort is made to give some color of the times while recognizing that articles from the 1920s and 1930s – such as The Romance of the Ranchos (1929), Halcyon Days of the Spanish Ranchos (1931), and Romance of a Rancho (1939) – idealized and romanticized the times.

Los Angeles itself was not a rancho, but a pueblo. The apocryphal story of its founding is that, on September 4, 1781, 11 men, 11 women, and 22 children left Mission San Gabriel, accompanied by the governor of Alta California, Felipe de Neve (1727-1784), soldiers, mission priests, and a few Native Americans a to settle a site along the Los Angeles River. With a speech by Governor de Neve, a blessing and prayers from the mission fathers, El Pueblo de Nuestra Senora la Reina de los Angeles de Porciuncula (The Town of Our Lady the Queen of the Angeles of Porciuncula) was established. The truth is a bit more complicated, and it is well told by Nathan Masters in Happy Birthday, Los Angeles! But is the Story of the City’s Founding a Myth?

Decades after the Pueblo’s founding, its sovereigns – Spain then Mexico – granted ranchos Rincón de los Bueyes and La Ballona to the pueblo’s residents or their families, who had already been using the land for grazing livestock. Mexico honored Spain’s grant, and the United States honored both.

Rancho Rincón de los Bueyes

On December 5, 1821, Bernardo Higuera (1790–1837) and Cornelio Maria Lopez (1792-1850) petitioned military commander Noriega to grant them Rancho Rincón de los Bueyes. Bernardo’s father, Joaquin Higuera (1755-1809) had been alcalde (mayor and chief judicial official) of the Pueblo in 1800. The petition, grant, and confirmation response are reported as follows:

To the Snr. CapN

Two days later, Noriega made an entry on the margin of the petition: “Pueblo de Nuestra Señora de Los Angeles. Dec. 7, 1821. It is granted if no prejudice result to the community. (Signed) Noriega.”

Bernardo Higuera and Cornelio Lopez, citizens of the Pueblo de Nuestra Señora la Reina de Los Angeles, and under the command of our honor, with the greatest respect and submission before your Excellency, appear and say that, possessing at the present time a number of cattle and not having any place so as properly to be able to keep them with a grazing ground of sufficient extent . . . . Therefore ask and beseech your extreme clemency to be pleased to grant to them the tract within this vicinity called Corral Viejo del Rincon so as that they may be able to place a corral for herding the said cattle unless it does some injury to the neighboring residents — a favor they expect from your extreme goodness and for which they will recognize themselves very grateful. May God preserve you many years.

(Romance of a Rancho, The Beverly Hills Citizen, Volume XVII – No. 2, June 23, 1939, pages 9, 12, which credits Prexcedes Arnaz de Lavigne, W. W. Robinson, and Nellie Van de Grift Sanchez (whose translation of a document by Don José de Arnaz appeared in “Touring Topics” in 1928).

The problem with Spain granting Rancho Rincón de los Bueyes to Higuera and Lopez on December 7, 1821, is that two months earlier, on September 27, 1821, Spain had ceded the land to a newly independent Mexico. However, it wasn’t until 1822 that the word of Mexico’s independence reached this frontier. It took until 1843 for Mexican Governor Manuel Micheltorena to confirm the grant of the 3,127-acre Rancho Rincón de los Bueyes to Higuera and Lopez.

Rincón de los Bueyes means “Corner of the Oxen.” It became known as such due to a large ravine at the south corner of the grant, which served as a natural corral. Today, La Cienega Boulevard courses through this ravine. (From John R. Kielbasa, Historic Adobes of Los Angeles.)

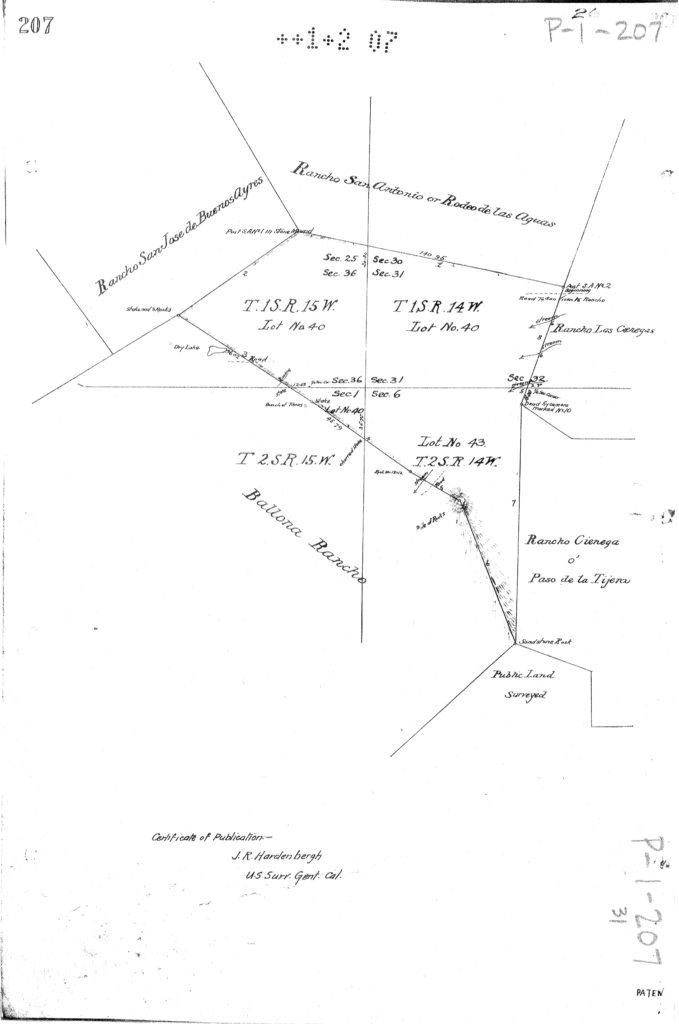

Rancho Rincón de los Bueyes’ northern limits are (starting from the northwest corner) Pico Boulevard (separating it from Rancho San Jose de Buenos Ayres) and Airdrome Street on the northeast (dividing it from Rancho Rodeo de los Aguas). To the east (heading south) Genesee Avenue then Fairfax Avenue divide it from Rancho Las Cienegas, then La Cienega Boulevard marks (roughly, since the road curves) the edge of Rancho Cienega o Paso de la Tiejera. Moving north from the southern tip, the border with Rancho La Ballona (along the west) follows a line to the top of the Baldwin Park Scenic Overlook stairs (marked on Arnaz’ 1875 survey as “6 Pile of Rocks”) from which point the limit line veers westerly in a straight line to the intersection of Overland Avenue and Pico Boulevard – running between Culver City’s Ince Boulevard and Van Buren Place, then following Faris Drive and Manning Avenue (until Manning turns north by Ashby Avenue).

1880 – Dividing the Rancho

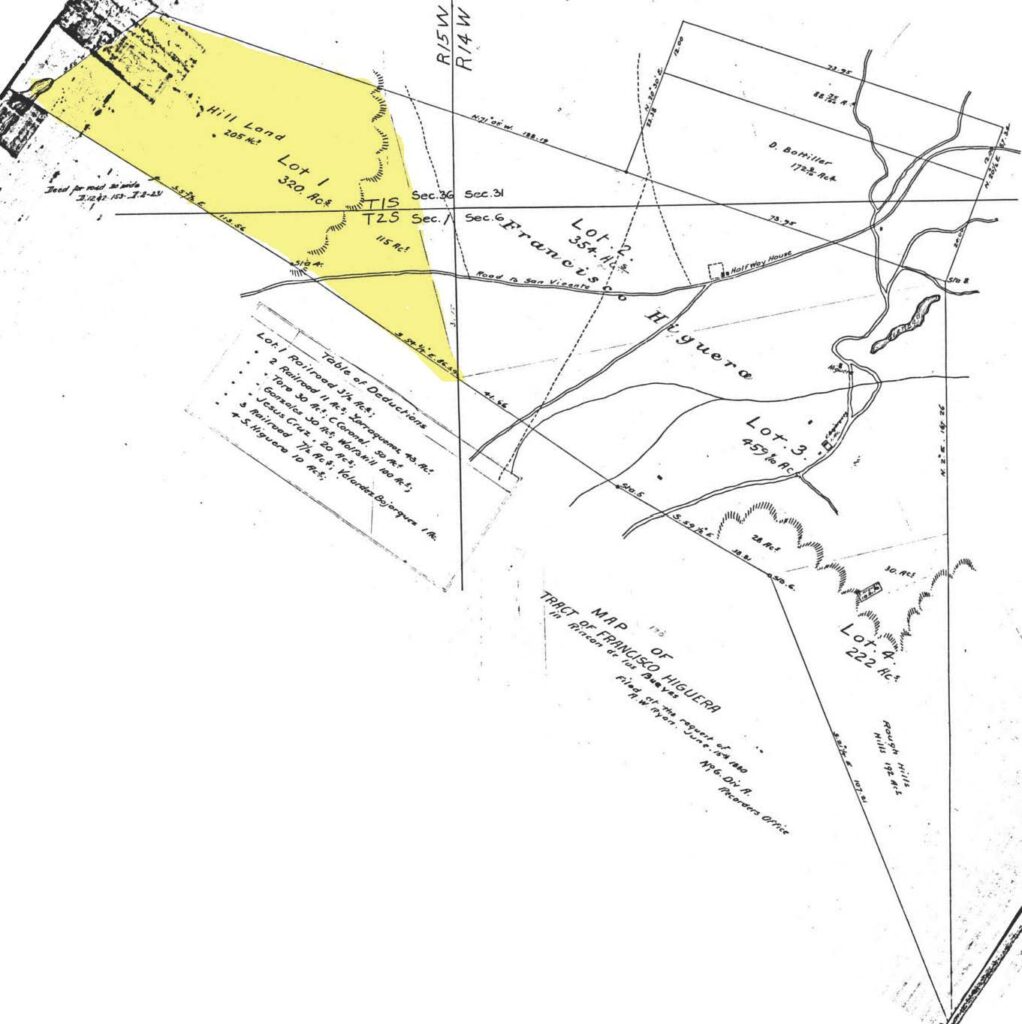

Bernardo Higuera’s sons, Jose Secondino Higuera (1822-1880) and Francisco Maria Higuera (1823-1903), inherited portions of their father’s land grant. Francisco subdivided his section in 1880.

Historian Sister Clementia Marie told this story about Francisco Higuera:

According to his granddaughter, Mrs. Ella Chevront, Francisco was working in the general store in the pueblo one day when a young girl and her mother entered the building. The girl made a deep impression on him because of her sad demeanor. In those days, etiquette did not permit a young man to speak to a young lady without a proper introduction. Somehow Francisco surmounted this barrier and found that the reason for the girl’s distress was that she was being forced to marry a man she did not love.

(The First Families of La Ballona Valley, Historical Society of Southern California Quarterly, XXXVII (March, 1955), pp. 51-52.)

The young heroine of our story was Senorita Ynez Ruiz, who was a native of the pueblo of Los Angeles but was then residing with her parents in San Fernando Valley. Eventually, Francisco found his way to Ynez’s home and obtained the required introduction, after which, he proceeded to throw his hat into the ring in the contest for the fair Ynez’s hand.

Francisco finally won his bride, thus this “Romance of the Ranchos” culminated with their wedding at San Gabriel Mission on March 10, 1849. The newly-weds made their permanent home on the Rancho Rincon de los Bueyes, where their hospitality and charity was known to all. The marriage of Francisco and Ynez was blessed with nine children: Manuela, Maria, Elpidio, Bernardo, Estaban, Rosario, Secundino, Enrique and Leovejildo.

Rancho La Ballona

In about 1819, José Agustín Antonio Machado and José Ygnacio Antonio Machado and Felipe Talamantes and Tomás Talamantes “moved in, under a permit from the military commander José de la Guerra y Noriega” to what would, in 1839, be granted to them as the nearly 14,000-acre Rancho Ballona. During those twenty years the Machado and Talamantes families, or their representatives, had stocked the ranch with “large cattle and horses and small cattle” and had improved it “with vineyards and houses and sowing grounds.”

(W. W. Robinson, Culver City, California: A Calendar of Events: in which is Included, Also, the Story of Palms and Playa Del Rey Together with Rancho La Ballona and Rancho Rincón de los Bueyes (Title Guarantee and Trust Company, 1941. Robinson’s was a seminal work on the subject. Another thorough and detailed history, gathered by Sister Mary Joanne Wittenburg, is listed in the bibliography, below.)

Historian Andrew F. Rolle (1922-2021) describes how title to the Ballona Rancho – also known as the Wagon Pass Rancho – was cleared through decades of effort. Here’s an excerpt:

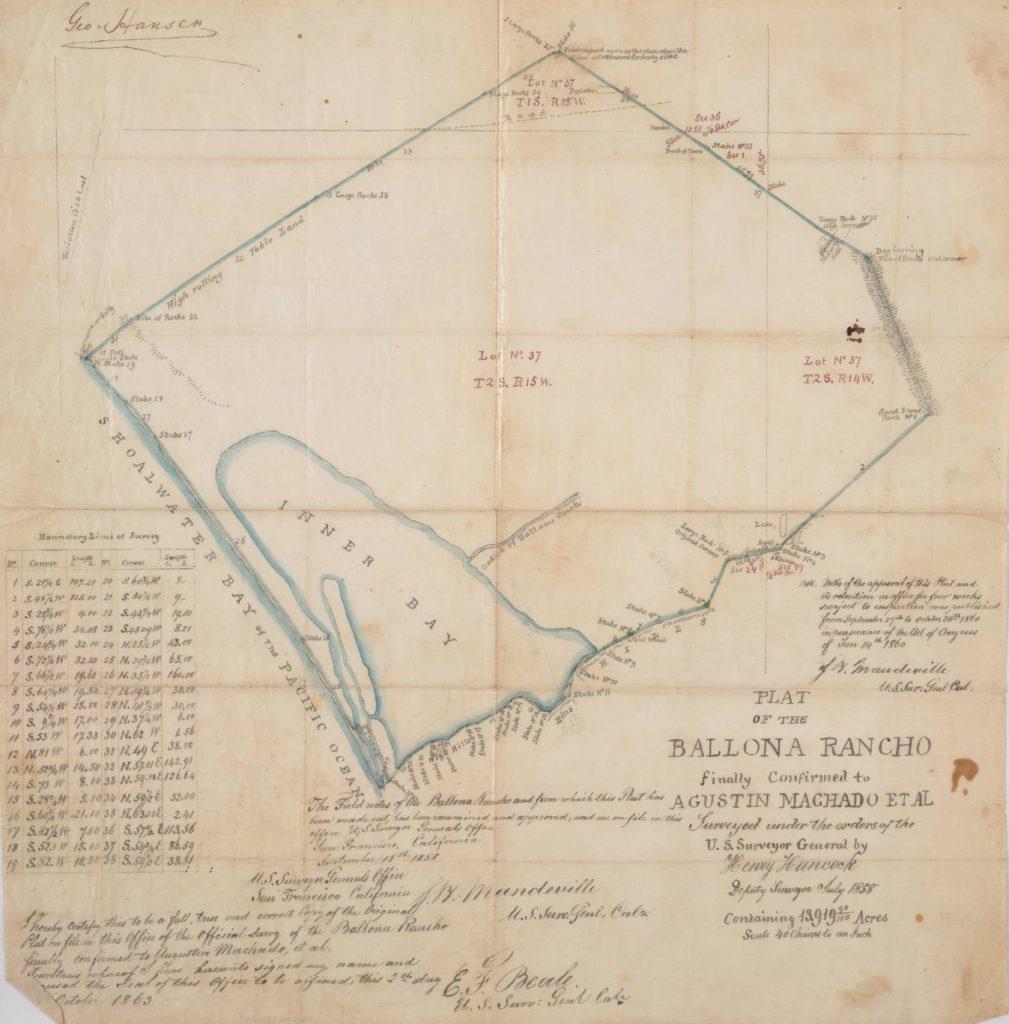

By 1851, like other traditional land holders in California, La Ballona’s owners were required to produce evidence before the California Land Commission that they possessed original ownership.

(Rolle, Wagon Pass Rancho Withers Away La Ballona, 1821 – 1952 (June 1952) The Historical Society of Southern California Quarterly.)

Fortunately, the Commission upheld the title of La Ballona in 1854. Nevertheless, like the Mexican authorities some twenty years earlier, the Commission was forced to describe the rancho’s boundaries in excessively general terms …. However fortunate the Machados and Talamantes were in obtaining approval of their title from the California Land Commissioners, there was one bogey which was to plague both of them and every subsequent owner of the rancho. This liability was the indefiniteness of its boundaries.

There was some bad news for Wagon Pass Rancho’s owners in 1860. That year the General Land Office in Washington disapproved the latest survey (1858) of La Ballona. J. W. Mandeville, United States Surveyor General at San Francisco, had given previous approbation to this survey. Now it was remanded to Mandeville for re-examination. Finally, after an investigation of the claims of various other appellants, the Surveyor General was authorized to publish tentative results. This he did on September 27, 1860, in the Los Angeles Star and other California newspapers.

Even after the death of Agustin Machado in 1865, litigation continued to rage over the rancho’s boundaries. On November 19, 1868, United States Secretary of the Interior O. H. Browning, wrote to the General Land Commissioner that he did not believe the boundary issue could ever be settled until the “proper” California courts made their decision. This was according to a law of 1859 which required that a survey of a rancho be submitted to a district court. Its decision was subject to appeal to the Supreme Court.

By December, 1873, it appeared that the final patent to La Ballona would be issued by the General Land Office in Washington. A battle had long been shaping up over who would receive this patent, however. That year the United States Government credited the owners or their heirs with still controlling some 14,000 acres. Weary of the litigation in which he had figured, Ygnacio Machado, eighty years old by 1870, had deeded most of his interest in La Ballona to relatives. This virtually insured the inevitable disintegration of the rancho. The allotment of parcels in 1868 to twenty-three more heirs revealed how fast La Ballona had withered away.

By 1870 Tomas Talamantes was also approaching the age of eighty, but he continued to battle those who wanted to capture the rancho’s title. By then an indescribable confusion was inextricably enmeshed in the problem of La Ballona’ s boundaries.

Personal testimony of early Californios regarding the locations of such land features as cottonwoods near salt marshes and lagoons along the sea finally led to the upholding of the July, 1858, survey. This credited La Ballona’s owners with 13,919 acres; but it was a diluted victory. By then the rancho had begun to lose its former identity. Much of the original tract had been sacrificed by mortgage or sold to meet heavy expenses of protracted litigation.

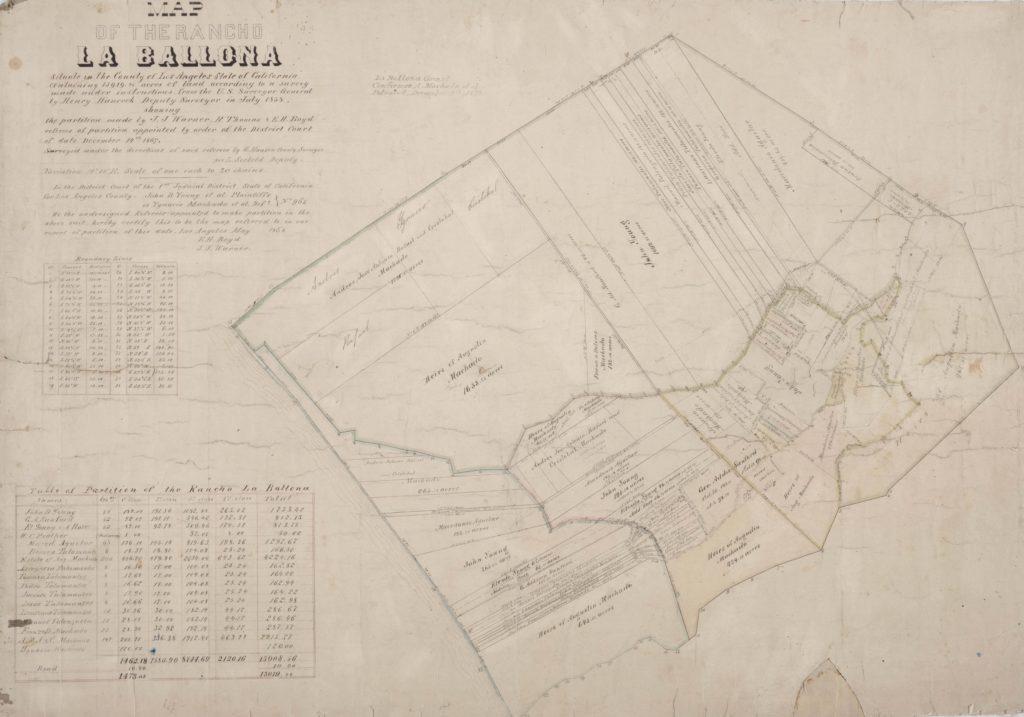

Partitioning La Ballona

In June 1854, Tomás Talamantes set in motion La Ballona’s breakup when he borrowed $1,500 from Benjamin D. Wilson and William T. B. Sanford. The note was to run for six months with interest at five per cent per month, and he secured it with a mortgage against his undivided quarter interest in the rancho. When Talamantes defaulted, his debt totaled $2,353.26 plus an additional $238.81 in costs. On December 31, 1855, Sheriff Alexander held a public auction in front of the Los Angeles Court House. Benjamin D. Wilson’s $2,000 bid prevailed.

In 1859, Wilson sold his quarter interest in La Ballona to John Sanford, James T. Young, and John D. Young for $4,500. The other three quarters of the rancho belonged to the Machados and to Felipe Talamantes’ heirs (Felipe had died in 1856). The ownership was “in common” – they all owned the rancho collectively, as if a corporation owned it and they owned shares in the corporation. As time passed, there were more “shareholders.”

In 1865, John D. Young petitioned the District Court so that he (and the other shareholders) would own specific within the rancho. Nearly two- and one-half years passed before the plat of the rancho and the other necessary documents arrived from Monterey and San Francisco and the division could proceed. (Wittenburg, Sister Mary Ste. Thérèse, The Machados & Rancho La Ballona (Dawson’s Book Shop, L. A., 1973), p. 48.) By that time, through inheritance and land sales, there were 32 owners, each of whom was entitled to a fair share of each of the four classes of land:

First class land was “arable land with water for cultivation,” i.e., from Ballona Creek.

(Report of the Survey of Partition 1868, Solano-Reeve Collection, Huntington Library, San Marino.)

Second class land was “arable land suitable for cultivation without water.”

Third class land was “Pasture land.”

Fourth class land was “Tide or Overflowed land.”

As Mar Vista historian Mark Crawford observed about the fourth-class land: “to cattlemen and farmers, what could be more worthless than beach property?”

When the court handed down its final judgment in 1868 the rancho had been pieced into 64 parcels of widely different shapes and sizes – as shown on the map below. Forty-seven years after its creation, Rancho La Ballona ceased to exist.

Although an American court had divided up La Ballona in 1868, it was not until December 8, 1873 that the United States government issued the final patent which confirmed the Machados’ and Talamantes’ title to nearly 14,000 acres.

The five Americans receiving shares in the partitioned La Ballona are listed before the Hispanic recipients:

John Dosier Young (1843-1915)

George Addison Sanford (1855-1941)

Elenda Young

Anderson/Addison Rose (1836-1902)

Willis Green Prather (1828-1891)

How they came to own the land, and some of their personal, often interwoven, histories, follows.

Benjamin D. Wilson – Mortgagee to Tomás Talamantes

Benjamin David/Davis “Don Benito” Wilson (1811-1878) of Nashville, Tennessee, was left fatherless at eight-years-old. By fifteen, he had started a trading business in Yazoo City, dealing with the local Choctaw and Chickasaw. He trapped beaver and crossed the plains and mountains to Santa Fe with the Rocky Mountain Fur Company, arriving in 1833 and keeping a store there for some time. In 1841 he followed the Old Spanish Trail to California with the Workman-Rowland Party.

Wilson, William Workman, John Rowland, the latter two living in Taos, William Gordon, William Knight (who later settled in the Sacramento Valley and after whom Knight’s Ferry and Knight’s Landing were named) and several others formed a party to go to Califjameornia. Wilson sold his business and in the first week of September, 1841, they started from their rendezvous in northern New Mexico, a place called Abiqui. They drove a herd of sheep with them to serve as food. They had, according to Wilson, an uneventful journey and arrived in Los Angeles early in November of the same year.

(Macfarland, John C., Don Benito Wilson, The Historical Society of Southern California Quarterly, vol. 31, no. 4 (1949) p. 276.)

Wilson intended to continue west to China (unlike Workman and Rowland, who had married Mexican women). However, he stayed, explaining:

After many unsuccessful efforts to leave California, and receiving so much kindness from the native Californians, I arrived at the conclusion that there was no place in the world where I could enjoy more true happiness, and true friendship, than among them. There were no courts, no juries, no lawyers, nor any need for them. The people were honest and hospitable, and their word was as good as their bond; indeed, bonds and notes of hand were entirely unknown among the natives.

(Macfarland, Don Benito Wilson, p. 276.)

In 1844, Wilson married a Mexican woman, Ramona Anselma Yorba (1828-1849) at Mission San Gabriel. She was a daughter of Don Bernardo Yorba, the owner of Rancho Cañón de Santa Ana, who gifted them a chunk of that rancho as a wedding present.

For many years, he operated a sizable mercantile establishment at the corner of Alameda and Macy Streets. At one time or another, he was the owner of all or part of the territory now covered by Westwood and the University of California at Los Angeles, and of practically all of what is now Pasadena. He subdivided and laid out the City of Alhambra. He and some of his associates acquired a great deal of the present Wilmington and sold it to Phineas Banning, who established the town of Wilmington.

(Macfarland, Don Benito Wilson, pp. 288-9.)

The Westwood and University of California area was part of Rancho San Jose de Buenos Ayres, which Wilson bought from grantee Jose Maximo Alanis in 1858. Wilson and W. T. B. Sanford received the patent from the Public Lands Commission in 1866.

Wilson was the second elected mayor of the City of Los Angeles (1851-1852), served three terms as Los Angeles County supervisor (1853, 1861-4) and three terms as a California State Senator. In 1864, he led an expedition to a peak in the San Gabriel Mountains that later would be named for him, Mount Wilson. His Los Angeles home became an orphanage after he relocated to his “Lake Vineyard” property in today’s San Marino. Cecilia Rasmussen, in a 1993 Los Angeles Times article, tells the story, which includes Wilson’s grandson, George S. Patton:

In 1854, Don Benito bought 128 acres of what would become the heart of the 2,400-acre city of San Marino. He built a lavish, two-story home with a wine cellar and tile roof, overlooking a lake. It cost a then-exorbitant $20,000. He surrounded his paradise with vineyards and citrus trees and called it Lake Vineyard. Five years later, Wilson – for whom Mt. Wilson above Altadena is named – added to his holdings. He purchased the 14,000-acre Rancho San Pasqual, which covered much of what would one day be Pasadena, Alhambra, South Pasadena, Altadena and San Marino.

(Cecilia Rasmussen, The house where San Marino’s founding fathers… (L. A. Times) Oct. 4, 1993)

Wilson’s son-in-law and business manager, James De Barth Shorb [1842-1896], owned the nearby 500-acre San Marino Ranch, which he had named after his family home in Emmitsburg, Md. It would also become the name of the future city. When high property taxes proved to be a headache, Wilson began selling large chunks to other ranchers. But he kept Lake Vineyard. And it was there in 1884, six years after Wilson’s death, that Wilson’s younger daughter, Ruth, made a home with her new husband, attorney George Smith Patton II. Within a year, Patton was elected Los Angeles County district attorney. He was 28. Also in 1885, Patton’s son and namesake was born. The father called him “The Boy.” His troops would later call him “Old Blood and Guts.” The future World War II general grew up on the Lake Vineyard Ranch with such young friends as Ignacio (Nacho) Callahan.

It has been said that Benjamin D. Wilson “was known to the Native Americans as Don Benito because of his benevolent manner in his treatment of Native American affairs.” (Wikipedia, as of Nov. 29, 2020.) Through a 21st century lens, he does not seem so benevolent. In an interview recorded by Thomas Savage in December 1877, on behalf of historian Hubert Howe Bancroft, Don Benito recounted, with the same empathy (or lack of it), his hunts for marauders – whether animal or human:

In the fall of 1844, my ranchman reported that a large bear had been close to the ranch house, and killed one of our best milk cows.

(Burgess, Michale & Mary, ¡Viva California! Seven Accounts of Life in Early California, (2006).)

I took an American named Evan Callaghan with me, and went to hunt for the grizzly. We separated, he went one path, and I went by the one leading from the cow’s carcass, followed the track a few hundred yards, and it went under an elder bush, covered with wild vines. Thinking the bear had passed out on the other side and going around the bush myself, I became entangled in another bush, in that condition the bear rushed from under his cover and bounced on behind me, bringing both the horse and myself to the ground; he bit me on the right shoulder into the lungs, and once in the left hip. By this time my dogs came up and the bear left me, a vaquero was coming to me when I managed to get up, and walked a few steps into an open space. I told the vaquero to take the saddle and bridle off the horse, as I supposed it was dead, but when the vaquero approached the horse, he raised his head, looked around, sprung to his feet, and ran home at full gallop with the saddle and bridle. Upon examination he was found entirely unharmed, his instinct had told him to feign death as long as he thought the bear was thereabouts.

It is well known that the bear is not a carrion beast. I was carried home and laid upon a blanket, where I bled so that I lost my sight and speech, though I still retained the power of my senses. A few native California women came to my assistance, and by their judicious nursing, I was soon on my feet again. But I still carry on my shoulder the marks of that bear’s tusks, in the form of a large hole, which can hold a walnut.

* * *

We trailed him to a marsh after diligent search for him, and almost despairing of finding him, my attention was called to a hole in the mud no larger than a black bird, when I became satisfied it was the bears nose, I got off my horse to give him a deadly shot in the head, when he jumped out with the rapidity of lightning and made for me, who stood about twenty feet from him, he came very near catching me a second time; a general fight followed, when the beast was finally put to death.

I have mentioned this part of the occurrence, to corroborate what I have been told by others, that bears have the sagacity to seek the healing of their wounds with application of mud.

Wilson’s narrative next turns to hunting Native Americans, whom he claimed were not only stealing horses, but also corrupting uncivilized Indians.

In 1845, about July or August, the Mojave and other Indians were constantly raiding upon the ranches in this part of the country, and at the request of the Governor, Don Pio Pico, who had promised me a force of eighty well mounted men, well-armed, I took command of an expedition to go in pursuit of the Indians.

I organized the expedition in San Bernardino, sent the pack train and soldiers, (less twenty-two which I retained with me) through the Cajon Pass, myself and the twenty-two went up the San Bernardino River through the mountains, and crossed over to what is now Bear Lake. Before arriving at the Lake we captured a village, the people of which had all left except two old women and some children. On the evening of the second day we arrived at the Lake, the whole Lake and swamp seemed alive with bear.

The twenty-two young Californians went out in pairs, and each pair lassoed one bear, and brought the result to the camp so that we had at one and the same time eleven bears.

This prompted me to give the Lake the name it now bears. [The lake today is known as Baldwin Lake, after Elias J. “Lucky” Baldwin, while the name Big Bear Lake was re-applied to a reservoir built nearby in 1884.]

* * *

I saw ahead of us four Indians on the path coming towards us ….

My object was not to kill them, but to take them prisoners that they might give me information on the points I desired.

The leading man of the four happened to be the very man of all others I was seeking for viz: the famous marauder Joaquín who had been raised as a page of the Church in San Gabriel Mission, and for his depredations, and outlawing, bore on his person the mark of the Mission, that is, one of his ears cropped off, and the iron brand on his hip. This is the only instance I ever heard or saw of this kind; that marking had not been done at the Mission, but at one of its ranches, (El Chino) by the Majordomo. In conversation with Joaquín, the command was coming on, and he then became convinced that we were on a campaign against him and his people, it was evident before, that he had taken me for a traveler. Immediately that he discovered the true state of things, he whipped from his quiver an arrow, strung it on his bow, and left nothing for me to do but shoot him in self-defense. We both discharged our weapons at the same time, I had no chance to raise the gun to my shoulder but fired it from my hand, his shot took effect in my right shoulder, and mine in his breast. The shock of his arrow in my shoulder caused me to involuntarily let my gun drop. My shot knocked him down disabled, but he discharged at me a tirade of abuse in the Spanish language such as I had never heard surpassed. I was on mule back, got down to pick up my gun, by this time my command arrived at the spot. The other three Indians were making off, out over the plains. I ordered my men to capture them alive, but the Indians resisted stoutly, refused to the last to surrender, wounded several of our horses, and two or three men, and had to be killed. Those three men actually fought eighty men in open plain, till they were put to death. During the fight Joaquín laid the ground uttering curses and abuse against the Spanish race and people. I discovered that I was shot with a poisoned arrow, rode down some five hundred yards to the river, and some of my men on returning and finding that Joaquín was not dead, finished him. I had to proceed immediately to the care of my wound.

[Having “finished” Joaquín, and with his own wounds tended to, Wilson soon returned to his manhunt.]

We were there met by the Chief of the Cahuillas, whose name was Cabezón (Big Head) with about twenty of his picked followers, to remonstrate against our going upon a campaign against his people, for he had ever been good and friendly to the whites. I made known to him that I had no desire to wage war on the Cahuillas, as I knew them to be what he said of them, but that I had come with the determination of seizing the two renegade Christians, who were continually depredating on our people. He then tried to frighten me out of the notion of going into his country, alleging, that it was sterile, and devoid of grass and water, and then ourselves, and our horses would perish there. I replied, that I had long experience in that sort of life, and was satisfied that a white man could go wherever an Indian went. I cut the argument short by placing the Chief and his party under arrest, and taking away their arms. He became very much alarmed, cried and begged of me not to arrest him, as he had always been a good man. I assured him that I would avoid if possible doing him or his people any harm, but had duties to perform, and I intended carrying them out in my own way. I then sternly remarked to him, there were but two ways to settle the matter: one was for me to march forward with my command, looking upon the Indians I met as enemies, till I got hold of the two Christians; the other was for him to detach some of his trusty men and bring the two robbers dead or alive to my camp, he again protested, but when he saw that I was on the point of marching forward, he called me to him, and said that he and his had held counsel together, and that if I would release his brother Adan, and some twelve more of his people whom he pointed out, himself and six or seven more remaining as hostages, Adan would bring those malefactors to me, if I would wait where we then had our camp. I at once acceded to his petition, released Adan, and the other twelve and let them have their arms.

* * *

In due time horsemen came back and reported that they believed all was right. I then had my men under arms, and waited the arrival of the party, which consisted of forty or fifty warriors. Adan ordered the party to halt some four hundred yards from my camp, himself and another companion advancing each one carrying the head of one of the malefactors, which they threw at my feet, with the evident marks of pleasure at the successful results of their expedition. Adan at the same time showing me an arrow wound in one of his thighs, which he had received in the skirmish that took place against those two Christians and their friends. Several others had been wounded but none killed except the two renegade Christians. By this time day was breaking, and we started on our return. The campaign being at an end, left the Indians with the two heads at Agua Caliente, after giving them all our spare rations, which were very considerable, as they had been prepared in the expectation of a long campaign.

After we reached our homes and dispersed, there arrived in my Ranch of Jurupa, some ten or twelve American trappers, (it was in the same summer), I related to them how our campaign ended down the Mojave, with the defeat of my force. They manifested a strong desire to accompany me back there; the Chief of that party was Van Duzen. I at once wrote to my old friend and companion Don Enrique Avila, to ask him if he would join me with ten picked men, and renew our campaign down the River Mojave. He answered that he would do so, con mucho gusto. He came forthwith and we started for the trip, twenty-one strong. Some seven or eight days after reached the field the operations, myself and Avila being in advance, we descried an Indian village. I at once directed my men to divide into two parties, to surround and attack the village, we did it successfully, but as on the former occasion, the men in the place would not surrender, and on my endeavoring to persuade them to give up, they shot one of my men, Evan Callaghan, (mentioned before) in the back.

I thought he was mortally wounded, and commanded my men to fire, the fire was kept up until every Indian man was slain. Took the women and children prisoners.

* * *

We found that these women could speak Spanish very well, and had also been neophytes, and that the men we had killed, had been the same who had defeated my command the first time, and were likewise Mission Indians.

We turned the women and children over to the Mission San Gabriel where they remained. Those three short campaigns left our district wholly free from Indian depredations, till after the change of Government.

Don Benito Wilson survived his campaign due to (in his words) a “civilized Comanche Indian, a trusty man, who had accompanied [him] from New Mexico to California” the “faithful Comanche, Lorenzo Trujillo.” (Except for Lorenzo Trujillo, General (“Old Blood and Guts”) Patton would not have been around for his military campaigns two generations later.) Find more on Lorenzo Trujillo at Riverside: Lorenzo and La Placita History and Agua Mansa: Californio Roots in the Inland Empire.

William T. B. Sanford – Mortgagee to Tomás Talamantes

Kentucky-born William Taylor Barnes Sanford (1814-1863) (the other Yanqui to whom Tomás Talamantes became indebted) was another rugged frontiersman who came to California across the Great Plains. A postmaster of early Los Angeles, Sanford gave Phineas Banning, the founder of Wilmington and the “father of the Port of Los Angeles,” his first job in California, clerking in Sanford’s San Pedro store. In 1856, Banning married Sanford’s younger sister, Rebecca Sanford (1837-1868).

In 1850, Sanford drove thirty tons of freight for Banning in a fifteen-strong wagon train through the West Cajón Valley into Utah, an unprecedented expedition from Los Angeles that opened trade with Salt Lake City. The trail he blazed over the mountaintop became known as “Sanford Crossing,” “Sanford Cutoff,” and the Sanford Pass Route.”

Although Benjamin Wilson and William Sanford both lent money to Tomás Talamantes, it was apparently Wilson alone who bought Tomás’ foreclosed quarter interest at auction in 1855. Any arrangements between Wilson and William Sanford to repay the latter are left to speculation.

In 1863, a boiler explosion aboard his brother-in-law Phineas Banning’s SS Ada Hancock killed William Sanford; he was 49.

Among the worst tragedies in the early annals of Los Angeles, and by far the most dramatic, was the disaster on April 27th to the little steamer Ada Hancock. While on a second trip, in the harbor of San Pedro, to transfer to the [steamer] Senator the remainder of the passengers bound for the North, the vessel careened, admitting cold water to the engine-room and exploding the boiler with such force that the boat was demolished to the water’s edge; fragments being found on an island even half to three-quarters of a mile away. Such was the intensity of the blast and the area of the devastation that, of the fifty-three or more passengers known to have been on board, twenty-six at least perished. Fortunate indeed were those, including Phineas Banning, the owner, who survived with minor injuries, after being hurled many feet into the air. …. Mrs. Banning and her mother, Mrs. [William T. B.] Sanford, and a daughter of B. D. Wilson were among the wounded.

(Harris Newmark [1834-1916], Sixty Years in Southern California, 1853-1913.)

John Sanford, James T. Young & John D. Young – Wilson’s Buyers

In May 1859, Wilson sold his quarter interest of Rancho La Ballona to his lending partner William Sanford’s younger brother, John Sanford (1820-1863) and also to James T. Young (1813-1866) and James’ seventeen-year-old son, John D. Young, for $4,500.

Wilson’s sale to John Sanford led to the establishment of the Sanford family ranch near Ballona Creek, which remained into the 20th century. According to a 1906 L. A. Times story, “half-wild” “halfbreed Mexicans,” “who resented the arrival of this first white family” in the Ballona Valley, rustled their cattle, cut off their hogs’ feet, and demolished their fences. The Sanfords were obliged to harvest their first crops armed with guns. John Sanford was murdered in 1863 by a stranger to whom he offered a ride in his buggy. The culprit, a notorious outlaw named Charles Wilkins, shot John in the back with his own pistol. Wilkins was tracked down in Santa Barbara, brought back to Los Angeles, and hanged by vigilantes who seized him from Sheriff Tomas Avila Sanchez. (L. A. Times, May 12, 1887.)

Cyrus Sanford (1827-1886), another brother who worked the Sanford ranch, lived and died violently. In 1857, Sanford and George Henry Carson (1832–1901) returned Phineas Banning’s horses after the thieves were pursued and at least one died in a gunfight. (L. A. Star, July 11, 1857.) Another story has Cyrus returning to the ranch one day when three “desperados” attacked him. These men had earlier roped a settler named Rains and dragged him to death behind their horses before tossing his corpse into a cactus bed. Cyrus killed two of his assailants and wounded the third.

Better documented is his September 1870 shooting of his drinking companion, Enoch Barnes. In his dying declaration to the sheriff, Barnes claimed “Sanford was in the habit of abusing his family when he was drunk,” and Barnes was trying to stop Sanford from returning home drunk. (L. A. Daily Star, Sep. 6, 1870.) In December 1870, Cyrus was sentenced to ten years in prison for the second-degree murder of Barnes. In 1872, Cyrus was released from prison when the California Supreme Court reversed his conviction because the judge’s instructions to the jury were oral rather than written. (People v. Sanford (1872) 43 Cal. 29.) It is not clear whether Cyrus was retried, but he apparently served no more time. Press accounts include a civil suit against his son, a trial for threats of violence, a notice disclaiming future debts by his wife Lucy A. Sanford and her children – who later got a restraining order against him and may have divorced him. It is said that Cyrus once was worth $100,000. But, by 1886, he had lost his wealth through a series of lawsuits and, despondent over this financial debacle, he committed suicide by shooting himself in the head.

George Addison Sanford (1855-1941) was another American who got his share of La Ballona through Wilson’s purchase of the foreclosed Tomás Talamantes’ land. He was Cyrus’ son and, thus, a nephew to William and John Sanford. George’s uncle John Sanford deeded him 912 acres of Rancho La Ballona in 1861 when George was a child of six. George’s allotment of third-class pastureland would encompass the first two subdivisions in Mar Vista and the community’s first business district. He spent his entire life on the Sanford ranch, located southwest of Inglewood Boulevard between Culver and Jefferson boulevards to McConnell Avenue in Del Rey. Ballona Creek flowed through the property and every year George flooded his pastures with a log dam – to the consternation of the neighboring ranchers. In 1906, the Machados (and others) petitioned the Los Angeles Board of Supervisors to force Sanford to break up his dam claiming the runoff was ruining their crops and turning a county road from Playa Del Rey into a bog. Sanford told them to move the road, as the dam had been established before the Civil War. (L. A. Times, May 12, 1887.) Sanford Street, which runs between the Marina Freeway and Ballona Creek, southwest of Centinela Avenue, is the only memorial in Ballona Valley to this pioneer family and their ranch. Weir Street, sort of a northern extension of Sanford Street between Inglewood Boulevard and Mesmer Avenue, is likely named for George’s dam.

Little is known about James T. Young other than that he was from Kentucky. (A “James T. Young” of Kentucky is memorialized at the Wilmington Cemetery; it is fair to assume that this is the same person.) After buying an interest in La Ballona from Wilson in May 1859, in September 1859, James bought a small adobe from Rafael Machado, a son of Agustín, and settled in Ballona to produce wine and cultivate fruit trees. James Young died before the 1868 final partition decree was handed down.

James’ son, John D. Young received the largest share of the one-fourth interest which Tomás Talamantes had forfeited and his father had purchased from Benjamin D. Wilson. The share, minus the fifty acres sold to Willis Prather, was divided between John’s mother Elenda Young (after whom Elenda Street in Culver City is named) and Addison Rose. “Since John D. Young already owned a portion of Ballona in his own right, he sold his inherited acreage to Addison Rose for $1,500.” (The Machados, p. 50.) In 1875 Young subdivided his acreage into 19 allotments. Three of these lots, Lots 6, 7, and 8, were again subdivided in 1880 into four- and five-acre pieces.

It was John D. Young who filed the petition in the District Court that resulted in the fragmentation of Ballona Rancho in 1868. John lived the life of a wealthy rancher by steadily selling his acreage piecemeal. He entered his trotters and “roadsters” in horse racing events. He participated in civic life by representing Ballona Township as a delegate to the Democratic County Convention, and as an occasional member of a Grand Jury. He spent the last thirty years of his life in a townhouse on Figueroa Street in downtown Los Angeles; he died in 1915 at the age of 73.

Anderson Rose (1836-1902) was another Yankee pioneer from Missouri who got a share of the partitioned Rancho La Ballona. In the partition lawsuit, Young v. Machado, Rose’s first name is given as “Addison.” (Wittenburg, Sister Mary Ste. Thérèse,The Machados & Rancho La Ballona (Dawson’s Book Shop, L. A., 1973), p. 48.)

Rose was just sixteen when he made the perilous trek from his native Missouri to Northern California in 1852, a journey that involved fending off Indian attacks. He settled initially in El Dorado County, a fitting destination for a man in search of gold, and took up mining activities. Luthor Ingersoll’s Century History, Santa Monica Bay Cities (1908) called him “the first American settler on La Ballona.” Rose acquired thousands of additional acres in and around Ballona and elsewhere over the years. He bred cattle and draft horses, raised lima beans, sugar beets, walnuts, and other cash crops, and operated a dairy that produced cheese, butter, and, according to the Outlook, “the best milk tasted in Santa Monica.” He lived on a ranch in Palms for many years; his son-in-law was William Dexter Curtis, the son of Joseph Curtis, one of the three founders of the Palms community. Anderson Rose died in 1902, aged 66. Rose Avenue is named after him.

Willis G. Prather (1828-1891) became connected to the Sanford clan when he married Hannah Young (1844-1915) (also of Randolph County, Missouri) in Tejon, Los Angeles County, California. He was 32; she was 16. Willis’ brother, William Freeman Prather (1824-1898), had married Rebecca’s sister, Marilda S. Sanford (1830-1924) 11 years earlier.

Hannah Young’s mother, Amanda M. (Sanford) Young (1818- ), was the youngest of the Sanford siblings mentioned above. Hannah’s uncle was William T. B. Sanford – Tomás Talamantes mortgagee; John Sanford and Cyrus Sanford were her uncles. And Rebecca Sanford, who is mentioned above for her marriage to Phineas Banning, was the second-youngest. Thus, Willis Prather was (by marriage) a nephew of the Sanfords and of Phineas Banning.

Prather spent little time in the Ballona Valley. The only record of him being there is when his daughter died there at under one-year-old in 1867. He moved from Missouri to San Joaquin, California, sometime between 1850 and 1852; married in Tejon in 1860; was back in San Joaquin County in 1861, 1863, and 1868-1879. Later, he resided mostly in Walla Walla, Washington, where he died in 1891. (See Ancestry.com.)

What does Ballona Mean (and how is it pronounced)?

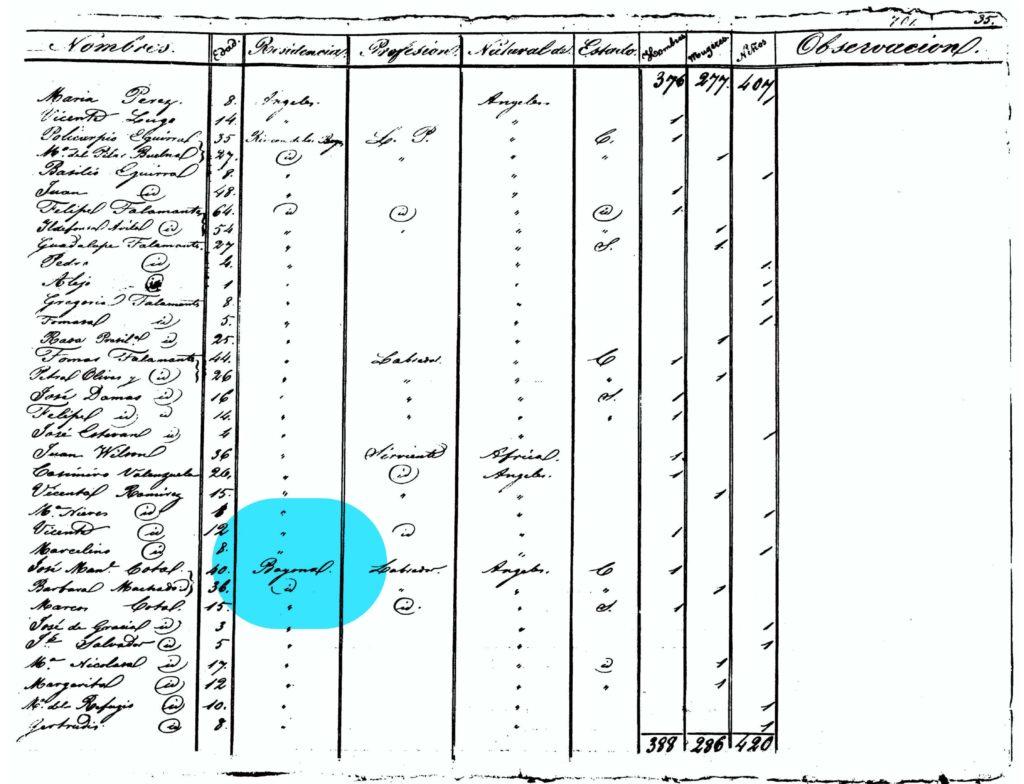

Many grew up with the Americanized pronunciation Buh-LOH-nuh. Others say By-OH-nuh. (Similarly, many use the Americanized pronunciation of Los Angeles instead of the original Spanish.) In the 1950s, Palms Historian David Worsfold urged the Spanish pronunciation BAY-ona in his article entitled, Valley Named for Spanish Port: Resident Tells Origin of ‘Ballona Name’ (Evening Star News and Venice Vanguard, Aug. 10, 1955): “In the first census of Los Angeles in 1836 [Padrón] it was spelled Bayona by one of the very few citizens who could read and write and that is surely the correct spelling.”

Worsfold continued, “This is confirmed by a story told by the Talamantes family to A. G. Rivera, Los Angeles County Interpreter, that the local area was named for the Spanish city of Bayona from whence one of their ancestors came.” Generations earlier, historians John Albert Wilson and Hubert Howe Bancroft used the spelling “La Bayona”: Wilson in his 1880 History of Los Angeles County and Bancroft in his 1888 California Pastoral.

As for the derivation of the Spanish city’s name, Worsfold wrote that it came from “good harbor”: “Bayona, Spain, and Bayonne, France, are located in the Basque country along the coast of the Bay of Biscay. The Basque word Baia means harbor and the word Ona means good, therefore Bayona means good harbor.”

Establishing Title in the Ranchos after United States Sovereignty

Pursuant to the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo (ending the Mexican-American War) the United States committed to honoring the Spanish and Mexican grants. Unfortunately for the Californianos, the ranchos’ ownership and boundaries – informal at best by modern American standards – had to be proven. During the process, many grantees lost their land to legal fees and/or sharp dealing. Decades later, a United States Senate subcommittee investigated whether Mexican Land Grants in California were “corruptly and fraudulently turned over to … private interests.” The Senators commented on the will of José Bartolomé Tapia, the grantee of the Rancho Topanga Malibu Sequit (including today’s Malibu) which had gone to Irishman Matthew Keller, rather than to Tapia: “This will [Tapia’s] shows the simple honesty of these old native Californians. It is too bad that they fell easy victims to the American settlers.” (Subcommittee of the Commmittee on Public Lands and Surveys of the United States Senate, 1929-1930, p. 114.)

Most of these grantees (and their heirs) did better than Tapia, even if it wasn’t easy or fast. Historian W. W. Robinson summarized the claims process concerning Rancho Rincón de los Bueyes and Rancho La Ballona:

In October of 1852 the families owning La Ballona and El Rincón filed their claims with the Commission which had been established the year before to settle all land claims.

(Culver City, California: A Calendar of Events: in which is Included, Also, the Story of Palms and Playa Del Rey Together with Rancho La Ballona and Rancho Rincón de los Bueyes, by W. W. Robinson, (Title Guarantee and Trust Company, 1941). )

The Machados and Talamantes had smooth sailing. The Board gave them its approval on February 14, 1854, and the United States District Court upheld the decision on appeal.

The Higueras were not so lucky. They were turned down at first. Not until the end of 1869 was their claim upheld in the District Court.

Partial Bibliography

Several histories, published and unpublished, of these ranchos’ evolution are referenced and linked above:

Ingersoll’s Century History, Santa Monica Bay Cities (1908)

W. W. Robinson, Culver City, California: A Calendar of Events: in which is Included, Also, the Story of Palms and Playa Del Rey Together with Rancho La Ballona and Rancho Rincón de los Bueyes (Title Guarantee and Trust Company, 1941).

Clementia Marie, The First Families of La Ballona Valley, Historical Society of Southern California Quarterly, XXXVII (March, 1955)

Sister Mary Joanne Wittenburg, The Machados & Rancho La Ballona (Dawson’s Book Shop, L. A., 1973)

Sister Mary Joanne Wittenburg, Two Men and Their Ranchos, unpublished (rev’d c. 2007) [focusing on Westwood Gardens area]

Burgess, Michael & Mary, ¡Viva California! Seven Accounts of Life in Early California (2006)

S. Ravi Tam (pseudonym), Distant Vistas, Exploring the Historic Neighborhoods of Mar Vista (2013)